The past month or so has seen a huge amount of activity around overly broad HIV criminalisation in the United States, culminating the reintroduction of the REPEAL HIV Discrimination Act by Congresswoman Barbara Lee.

As well as on-going arrests and prosecutions of individuals for alleged non-disclosure (and some excellent reporting on certain cases, such as that of Michael ‘Tiger Mandingo’ Johnson in Missouri or of two new cases on the same day in Michigan) new problematic HIV-related criminal laws have been proposed in Alabama, Missouri, Rhode Island and Texas.

Fortunately, most of these bills have been stopped due to rapid responses from well networked grass roots advocates (many of whom are connected via the Sero Project’s listserv) as well as state and national HIV legal and policy organisations, including the Positive Justice Project.

REPEAL HIV Discrimination Act

On March 24th, Congresswoman Barbara Lee reintroduced a new iteration of the REPEAL HIV Discrimination Act (H.R.1586), “to modernize laws, and eliminate discrimination, with respect to people living with HIV/AIDS, and for other purposes”.

The full text of the bill can be found here.

The last time the REPEAL Act was introduced, in 2013, it had 45 co-sponsors before dying in committee. The first iteration, introduced in 2011, achieved 41 co-sponsors.

As of April 15th, the 2015 iteration has three co-sponsors, two Democrats – Jim McDermott and Adam B Schiff – and one Republican, Ileana Ros-Lehtinen.

As in 2011 and 2013, the bill has been referred to three House Committees: Judiciary, Energy and Commerce, and Armed Services.

Back in 2013, the Positive Justice Project produced an excellent toolkit that provides advocates with resources which “can be used in outreach efforts, including a guide for letter writing campaigns, calling your representative’s state and Washington D.C. offices, or meeting with your representative or the representative’s legislative staff.”

If you’re in the US, you can also show Congress that you support this bill at: https://www.popvox.com/bills/us/114/hr1586

Alabama

On April 1, 2015 the House Judiciary Committee of the Alabama Legislature held a hearing on HB 50, proposed by Democrat Representative Juandalynn Givan, that would increase the penalty for exposure or transmission of a sexually transmitted infection from a class C misdemeanour (punishable by up to 3 months in jail and a $500 fine) to a class C felony (punishable by up to 10 years in prison).

Representative Givan was apparently inspired to propose the bill after reading about a pastor in Montgomery, Alabama, who admitted in an October 2014 sermon that he was living with HIV and engaging in sex with women in his congregation without having disclosed his status. (He wasn’t prosecuted, but appears to have lost his job, as of the last news report in December 2014.)

In an interview in March 2015, she told AL.com that Alabama is one of only 16 states in the nation where it is a misdemeanour rather than a felony to ‘knowingly expose another person to a sexually transmitted disease’.

“What this bill is about is responsibility and accountability…The aim of this bill is not to punish those people with a sexually transmitted disease but to hold those people accountable,” that knowingly transmit dangerous illnesses to other people.

Some of the testimony before the House Judiciary Committee – most of it against the bill – is reported (rather poorly) in the Alabama Political Reporter.

Before the hearing began, the Positive Justice Project Steering Committee sent a powerful letter to the members of the House Judiciary Committee, voicing their strong opposition to the bill.

Medical experts and public health officials agree that criminalizing the conduct of people living with HIV does nothing to decrease the rates of infection, and may actually deter conduct and decisions that reduce disease transmission. Consequently, the American Medical Association, HIVMA, ANAC, and NASTAD have issued statements urging an end to the criminalization of HIV and other infectious diseases. Notably, the U.S. Department of Justice recently issued “Best Practices Guide to Reform HIV-Specific Criminal Laws,” which counsels states to end felony prosecutions of people living with HIV as contrary to the relevant science and national HIV prevention goals.

The bill remains with the House Judiciary Committee, but seems unlikely to be passed given that there are no co-sponsors.

Missouri

On March 10th, Republican Representative Travis Fitzwater introduced HB 1181, which proposed adding ‘spitting whilst HIV-positive’ to Missouri’s (already overly draconian) current HIV-specific criminal statute.

It is unclear what caused Rep Fitzwater to introduce the bill. However, advocacy against it was swift, with the local chapters of both ACLU and Human Rights Campaign, and Missouri-based HIV advocate, Aaron Laxton, planning to testify against it within days of it being introduced.

Although the bill was scheduled for a public hearing before the Civil and Criminal Proceedings Committee on April 7th, the community’s quick response meant the bill was not heard. According to Laxton, “within a matter of hours every member of the Civil and Criminal Proceedings Committee has received calls, emails, tweets and messages from many people” against the bill.

The proposed bill now appears to be dead, and advocacy in Missouri is now focused on modernising the existing HIV-specific law (which includes criminalising biting whilst HIV-positive) to take into account the latest science around HIV risk and harm.

Rhode Island

On February 24th, Republican Representative Robert Nardolillo introduced a new HIV-specific criminal law (H 5245) that would have criminalised HIV non-disclosure in the state for the first time.

In an interview with Zack Ford on thinkprogress.org, Rep Nardolillo said that as a survivor of sexual abuse he was surprised to discover that Rhode Island law does not allow for harsh enough penalties if HIV is passed on during a sexual assault.

However, although his proposed bill created a felony when someone with HIV “forcibly engages in sexual intercourse,” it also criminalised when someone “knowingly engages in sexual intercourse with another person without first informing that person of his/her HIV infection.”

The entire hearing before the Rhode Island House Judiciary Committee was captured on video, and an excellent blog post by Steve Ahlquist on RIFuture.org highlighted both Rep Nardolillo’s ignorance of the potential harms of the bill, and the sustained and powerful testimonies against the bill from public health experts, people living with HIV and HIV NGOs alike.

Ahlquist concludes, “In the face of such strong opposition, it seems extremely unlikely that this legislation will advance out of committee.”

All testimonies are available to view in short video clips on the blog. You can also read the written testimony of the AIDS Law Project of the Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders (GLAD) here.

Texas

On February 25, Republican Senator Joan Huffman introduced SB 779, which would essentially have created an HIV-specific criminal law by the back door.

Texas repealed its previous HIV-specific criminal law in 1994 and uses general criminal statutes, including attempted murder and aggravated assault, for potential or perceived HIV exposure and alleged HIV transmission cases.

According to the Advocacy Without Borders blog, “SB 779 proposes to amend the state Health and Safety Code to allow for HIV test results (which are currently confidential) to be subpoenaed during grand jury proceedings – and for a defendant’s medical records to be accessed without their consent to establish guilt/innocence and also potentially to be used to determine sentencing. Essentially, this bill proposes to criminalize having HIV.”

The proposed law, and a number of other proposed HIV-related laws, was also critiqued in a Dallas Voice article highlighting the opinion of Januari Leo, who works with Legacy Community Health Service.

Leo, a longtime social worker who has worked with clients living with HIV, is blunt about the three bills: “They would criminalize HIV. HIV isn’t a crime. It’s a public health problem…These new bills use HIV status as a crime, against people who are suspects in a crime but have yet to be proven guilty. They’re allowing prosecutors to use private medical records, as mandated under HIPPA, as a weapon.”

Although it was considered in a public hearing before the State Affairs Committee on April 16, it now appears to be dead.

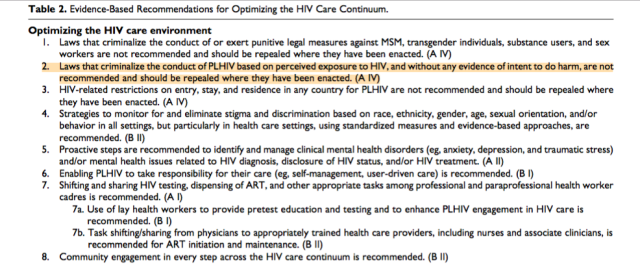

In many settings, optimizing the HIV care environment may be the most important action to ensure that there are meaningful increases in the number of people who are tested for HIV, linked to care, started on ART if diagnosed to be HIV positive, and assisted to achieve and maintain long-term viral suppression. Overcoming the legal, social, environmental, and structural barriers that limit access to the full range of services across the HIV care continuum requires multistakeholder engagement, diversified and inclusive strategies, and innovative approaches. Addressing laws that criminalize the conduct of key populations and supporting interventions that reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination are also critically important. People living with HIV also require support through peer counseling, education, and navigation mechanisms, and their self-management skills reinforced by strengthening HIV literacy across the continuum of care.

In many settings, optimizing the HIV care environment may be the most important action to ensure that there are meaningful increases in the number of people who are tested for HIV, linked to care, started on ART if diagnosed to be HIV positive, and assisted to achieve and maintain long-term viral suppression. Overcoming the legal, social, environmental, and structural barriers that limit access to the full range of services across the HIV care continuum requires multistakeholder engagement, diversified and inclusive strategies, and innovative approaches. Addressing laws that criminalize the conduct of key populations and supporting interventions that reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination are also critically important. People living with HIV also require support through peer counseling, education, and navigation mechanisms, and their self-management skills reinforced by strengthening HIV literacy across the continuum of care.