In many countries around the world, people with HIV are being made criminally liable for HIV prevention.

Despite strong recommendations against this overly broad use of the criminal law by UNAIDS and the Global Commission on HIV and the Law, the latest report from the Global Network of People Living with HIV and the HIV Justice Network highlights that new laws continue to be proposed and enacted, and more prosecutions are taking place than ever before.

This 30 minute video from the HIV Justice Network, filmed at an international meeting on HIV prevention and criminal law in Toronto in April 2013, features interviews with social scientists, researchers and legal and public health experts who have studied the public health impact of HIV criminalisation.

To download this video please click on the Vimeo link on the bottom right of the video which takes you the video on the HIV Justice Network’s Vimeo channel. Here you will have the option to download Mobile, SD and HD files.Studies cited in the film

- Lazzarini Z et al. Evaluating the Impact of Criminal Laws on HIV Risk Behavior. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, Vol. 30, No. 2, Summer 2002.

- Burris S et al. Do Criminal Laws Influence HIV Risk Behavior? An Empirical Trial. Arizona State Law Journal, 2007; Temple University Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2007-03.

- Galletly C and Pinkerton S. Conflicting Messages – How Criminal HIV Disclosure Laws Undermine Public Health Efforts to Control the Spread of HIV. AIDS and Behavior, 10, 451-461, 2006.

- Galletly C et al. Sexual behavior, stigma, perceived hostility, comfort with disclosure and New Jersey’s HIV exposure law. American Journal of Public Health, 102(11), 2135-2140, 2012.

- Mykhalovskiy E. The problem of “significant risk”: Exploring the public health impact of criminalizing HIV non-disclosure. Soc Sci Med. Sep;73(5):668-75, 2011.

- Adam B et al. How criminalization is affecting people living with HIV in Ontario. Ontario HIV Treatment Network, 2012.

- Adam B et al. Impacts of Criminalization on the Everyday Lives of People Living with HIV in Canada. Sex Res Soc Policy, August 2013.

- O’Byrne P and Gagnon M. HIV Criminalization and Nursing Practice. Aporia 4(2), 5-34, 2012.

- Hoppe T. Controlling Sex in the Name of Public Health, Social Problems, Vol. 60, No. 1, February 2013.

- Sero Project National Criminalization Survey 2012.

- O’Byrne P et al. Nondisclosure prosecutions and population health outcomes: examining HIV testing, HIV diagnoses, and the attitudes of men who have sex with men following nondisclosure prosecution media releases in Ottawa, Canada. BMC Public Health. Feb 1; 13:94, 2013.

- O’Byrne P et al. Nondisclosure Prosecutions and HIV Prevention: Results From an Ottawa-Based Gay Men’s Sex Survey. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. Jan-Feb; 24(1):81-7, 2013.

In addition, Patrick O’Byrne and colleagues at the University of Ottawa have reviewed all studies published to date on the public health impact impact of HIV criminalisation, which summarises all of the studies above, as well as others not mentioned in the documentary.

FEATURE STORY: Why overly broad HIV criminalisation is doing more harm than good

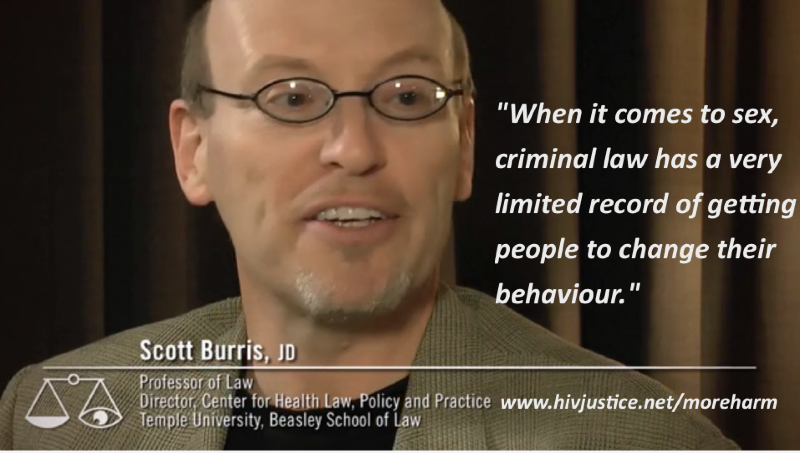

The most commonly cited rationale of the criminal law is to deter morally unacceptable behaviour through fear of punishment. Scott Burris and Zita Lazzarini were the first to explore whether US laws that criminalised HIV non-disclosure had the impact that the lawmakers intended.

Zita Lazzarini: We found that whether you lived in a state with a law or without a law had absolutely no effect.

Scott Burris: Criminal law is generally a very blunt tool, anyway. And if you think about it, punishment and fear rarely brings out the best in people, when they’re making individual behaviour decisions. And certainly, when it comes to sex, criminal law has a very limited record of getting people to change their behaviour.

Carol Galletly has added much to the body of evidence on the impact of laws that criminalise HIV non-disclosure. Working with a number of colleagues, she published a number of studies, including this one in 2006 and this one in 2012 examining whether or not these laws are having the impact they were intended to have.

Carol Galletly: We thought of every single way these laws could possibly be effective. Do HIV-positive individuals reduce number of sex partners? Do they choose only positive sex partners more than people who don’t know about the law? Are they abstinent more? Do they practice safer sex more? Do they engage in oral sex or less risky activities? So we looked at all these things and the data just stacked up – there were no significant differences. The strongest predictor of disclosure was actually comfort with disclosure. So what I concluded was, if you really want people to disclose, then what you should probably do is increase their comfort, do interventions, do whatever. And don’t do laws that could jeopardize people disclosing.

Most laws and prosecutions focus on disclosure – in other words, whether or not the person with diagnosed HIV told their sexual partner before having sex. Whilst this may be the right thing to do, does this actually benefit HIV prevention? Eric Mykhalovskiy organised the workshop precisely because his own research found that criminalising non-disclosure was having the opposite effect of what was intended.

Eric Mykhalovskiy: We see how significant now disclosure, or questions around disclosure, are within HIV prevention counselling, to the point that there is too much of a focus. You know, Barry Adam and others have emphasised repeatedly that disclosure is not an effective HIV prevention mechanism. And yet what seems to have happened is that the criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure has placed disclosure at the centre of people’s concerns around HIV prevention. And that is, I think, a serious challenge for people who are enlisted with the responsibility of trying to ensure that HIV transmission is lessened.

Barry Adam is Senior Scientist and Director of Prevention Research at the Ontario HIV Treatment Network and lead author of How criminalization is affecting people living with HIV in Ontario.

Barry Adam: Disclosure has become a bit of a red herring I think, in terms of HIV prevention because HIV prevention can and has for a long time happened without disclosure, anyways. To require disclosure doesn’t necessarily help. Sometimes, it could even hinder the process by creating a false sense of security among those who think that, if disclosure doesn’t happen, that their partner is negative. The social science evidence shows that, when people often get into the disclosure area, it’s in order to give themselves permission to have unprotected sex! People actually do have to know what their HIV status is in order to disclose it. And, there is a good deal of science these days that suggests that, it’s people who don’t know, who are newly infected, who are actually doing a lot of the infection.

Studies by Eric Mykhalovskiy, Chris Sanders and Martin French (the latter two are currently undertaking research studies and have not yet published their findings) have uncovered an unanticipated negative impact of HIV criminalisation on the healthcare workers who test and treat people with HIV, complicating their practice as public health professionals. They found that the criminal law is creating a chill, closing down discussions about HIV on both sides. (An in-depth report on the impact of HIV criminalisation on nursing practice can be found here.)

Chris Sanders: Criminalisation has complicated post-test counseling. Nurses are finding that clients shut down, they become very unwilling to speak openly about their sexual behaviour and they don’t want to share contact information because they’re worried that it might come back if they’re later charged with non-disclosure. And so, it makes nurses’ work more difficult. And that can impact HIV prevention as public health relies on contact tracing to be able to do quite a bit of their prevention work.

Martin French: I’m looking at this in Canada and the United States, and in spite of the fact that there are different approaches to public health I’m seeing some similar effects in terms of the anxiety that a number of providers are feeling about the issue of criminalisation as they counsel patients with respect to disclosure.

Trevor Hoppe found another, more sinister impact on healthcare workers. During his PhD research he discovered that some heath officials in Michigan’s public health system appeared to be invested in prosecuting people with HIV for not disclosing their status, resulting in some potentially problematic outcomes for HIV prevention.

Trevor Hoppe: This is the first piece of evidence that some health departments may be playing a role in facilitating criminal prosecutions. I can understand why people living in some of these communities would think twice before talking to health officials about their lives openly and honestly, given what health officials reported to me.

One of the most worrying aspects of HIV criminalisation is the additional disincentive it plays in a person’s willingness to take an HIV test: a significant number of new infections come from people who are undiagnosed. But testing is not just about knowing one’s HIV status to modify behaviour, it’s also the gateway to accessing HIV treatment and care.

New guidelines from the World Health Organization now highlight that HIV treatment works not only to keep people alive and well for a lifetime, but also prevents new infections by reducing HIV to undetectable levels. Where there is no virus, there can be no transmission. Since treatment is also prevention, then not testing or accessing treatment, hurts not only the individual but also the communities in which they live, harming the broader public health.

Laurel Sprague is the Research Director of the Sero Project, and oversaw their 2012 national HIV criminalisation survey.

Laurel Sprague: We asked people whether they thought it was not reasonable, somewhat reasonable or very reasonable to avoid getting an HIV test, or to avoid accessing treatment if someone tested positive because of HIV criminalisation. Those numbers should be zero. We shouldn’t have legal reasons for people not to get tested. We shouldn’t have a legal reason for people not to access care. And half of our respondents said that it was reasonable to avoid HIV testing because of HIV criminalisation and 42% of our respondents said it was reasonable, somewhat, or very reasonable to avoid getting HIV care once you’ve tested positive.

Patrick O’ Byrne is lead author of the 2013 review article, HIV criminal prosecutions and public health: an examination of the empirical research. He has also studied the impact of HIV prosecutions on gay men and documented how fear of HIV criminalisation has impacted their sexual and testing practices.

Patrick O’Byrne: Nobody – guys who were negative, guys who were positive – could make a distinction between the public health department and the police. It was a single institution. And this is problematic, right? How can you provide health care services when people think that you are a police agency? How do you provide care when people won’t access it? The laws have effectively rendered your HIV prevention health professionals useless.

Richard Elliott is the Executive Director of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, and was an intervenor when the Supreme Court of Canada heard HIV criminalisation cases in 1998 and 2012.

Richard Elliott: How can it not have an impact on people and their decision as to whether or not to find out their HIV status, if you risk becoming a criminal. It may not at the end of the day dissuade a large number of people, but I think, it does dissuade a significant number of people and it probably, based on the evidence we have, dissuades some of those who are most likely to actually benefit from learning their HIV status, and all of the potential benefits to them, and others that may flow from that. So, why would we want to create an additional barrier, and why would we want to create a barrier to people actually seeking help from the helping professions? Because if we conscript those helping professions, to basically, become agents of law enforcement, that undermines their ability to help people, and that actually undermines the health of all of us.

Criminalisation is a divisive issue with strong opinions often informed by morality and a desire to achieve justice by punishing perceived wrongdoing. However, understanding the impact of HIV criminalisation on public health is critical to making informed policy decisions.

The 2013 UNAIDS guidance note, Ending overly-broad criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission: Critical scientific, medical and legal considerations aims to ensure that any application of criminal law in the context of HIV achieves justice and does not jeopardise public health objectives.

The entire guidance is available below, and can be downloaded here.

The HIV Justice Network produces videos in conjunction with georgetown media that we hope are useful for both education and advocacy. If you find this or our other videos useful, please let us know.