A new report, launched at AIDS 2010 in Vienna last month, recommends that the Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General establish a consultation process to inform the development of prosecution guidelines for cases involving allegations of non-disclosure of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.

HIV Non-Disclosure and the Criminal Law: Establishing Policy Options for Ontario contributes to the development of an evidence-informed approach to using the criminal law to address the risk of the sexual transmission of HIV infection in Ontario, and offers the most comprehensive, current discussion of the criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure in Canada.

The report was triggered by the absence of policy-based discussion of this issue amongst key decision makers in government and by community concerns about the intensified use and wide reach of the criminal law in circumstances of HIV non-disclosure.

In Canada, people living with HIV have a criminal law obligation to disclose their status before engaging in activities that pose a “significant risk” of HIV transmission. The report emphasises that uncertainties associated with that obligation and interpretations of the obligation that are not informed by current scientific research on HIV transmission risks are foundational to current problems in the use of the criminal law to regulate the risk of the sexual transmission of HIV and explores various forms of evidence relevant to a thorough policy consideration of the use of the criminal law in situations of HIV non-disclosure in sexual relationships.

York University has produced a 1200 word pdf summary of the report which I’m including in its entirety below. A pdf of the entire report can be downloaded here.

Title: The criminal law about sex and HIV disclosure is not clear

What is this research about?

According to the Supreme Court of Canada, HIV-positive people are required to disclose their status before engaging in sexual activities that pose a “significant risk” of transmitting HIV to a sex partner. Canadian courts, however, have yet to clearly define what sex acts, in what circumstances, carry a “significant risk.” This has led to an expansive use of the criminal law and created a problem for people with HIV—they can face criminal charges even though the law is not clear about when they must tell sex partners about their HIV. For example, people with HIV who are taking anti-HIV medications are much less likely to transmit HIV during sex, even where no condoms are used. But Ontario police and Crown Attorneys continue to interpret “significant risk” broadly. In fact, charges have been pursued in cases where, on a scientific level, there is little risk of HIV transmission.

This uncertainty has created problems not only for people with HIV but also for public health staff, and health care and social service providers. It has challenged these front-line workers in their attempts to counsel and support people with HIV. It has also caused many people with HIV to be further stigmatized. The media, in its coverage of these cases, has tended to exaggerate the risk of HIV transmission at a time when more and more experts have come to think of HIV as a chronic and manageable infection.

Despite these problems, and over 100 criminal cases in Canada, there has been a lack of evidence to inform public discussion about this important criminal justice policy issue. In Ontario, policy-makers have not weighed in publicly on the criminalization of people who do not reveal to their sex partners that they have HIV.

What did the researchers do?

A project team, led by Eric Mykhalovskiy, Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at York University, set out to explore how the criminal law has been used in prosecutions involving allegations of HIV non-disclosure. The team included members of community organizations in Toronto and front-line workers, some of whom are living with HIV. Their goal was to create evidence and propose options to guide policy and law reform. They created the first national database on criminal cases of HIV non-disclosure in Canada. Professor Mykhalovskiy interviewed over 50 people with HIV, public health staff, and health care and social service providers to find out how the criminal law is affecting their lives or their work—another Canadian first.

What did the researchers find?

From 1989 to 2009, Canada saw 104 criminal cases in which 98 people were charged for not disclosing to sex partners that they have HIV. Ontario accounts for nearly half of these cases. Most of the cases have occurred since 2004. Half of the heterosexual men who have been charged in Ontario since 2004 are Black. Nearly 70% of all cases have resulted in prison terms. In 34% of these cases, HIV transmission did not occur.

Looking at the cases in Ontario and Canada, the researchers found inconsistencies in the evidence courts relied on to decide whether a sex act carried a significant risk of HIV transmission. They also found inconsistencies in how courts have interpreted the legal test established by the Supreme Court, and inconsistencies between court decisions in cases with similar facts. It appears, in some cases, that police and Crown prosecutors have not been guided by the scientific research when deciding whether to lay charges or proceed with a prosecution.

Because it is important to understand the scientific research when assessing whether there is a “significant risk” of HIV transmission during sex, the researchers included in their report a succinct summary of the leading science. The risk, in general, is low. Activities like unprotected sexual intercourse carry a risk that is much lower than commonly believed. Most unprotected intercourse involving an HIV-positive person does not result in the transmission of HIV. But the risk of transmission is not the same for all sex acts and circumstances. Antiretroviral therapy, however, can reduce the amount of HIV in a person’s bloodstream and make the person less infectious to their partner. Also, because of antiretroviral therapy, HIV infection has gone from being a terminal disease to a chronic, manageable condition in the eyes of many experts and people living with the virus.

Many people with HIV who were interviewed remain concerned that even if they disclose their HIV, their sex partners might complain to police. Health care and service providers stated that they are confused by the vagueness of the law. They also stated that criminalizing HIV non-disclosure prevents people from seeking the support they need to come to grips with living with HIV and disclosing to partners. But people with HIV and their providers have many suggestions for improving public policy and the law. The “significant risk” test needs to be clarified. The public health and criminal justice systems need to work together. And policies and procedures to guide Crown Attorneys need to be put in place.

How can you use this research?

Policymakers have several options to respond to the lack of clarity in the law and the resulting expansive use of the law. They can continue to let police, Crown Attorneys, and courts deal with cases as they arise. They can work to amend the Criminal Code. But the best solution, in the short term, would be the development of policy and procedures to guide Crown Attorneys working on these types of cases. The Ontario Ministry of the Attorney General should establish a consultation process to help develop policy and procedures for criminal cases in which people have allegedly not disclosed that they are HIV-positive to their sex partners.

What you need to know:

The criminal law can lead to very serious consequences for people who are charged or convicted. So policymakers need to make sure that the criminal law about HIV disclosure is clear and clearly informed by scientific research about HIV transmission. They also need to look to research to assess whether the law is having unintended consequences that get in the way of HIV prevention efforts.

About the Researchers:

Eric Mykhalovskiy is an Associate Professor and CIHR New Investigator in the Department of Sociology. Glenn Betteridge is a former lawyer who now works as a legal and health consultant. David McLay holds a PhD in biology and is a professional science writer.

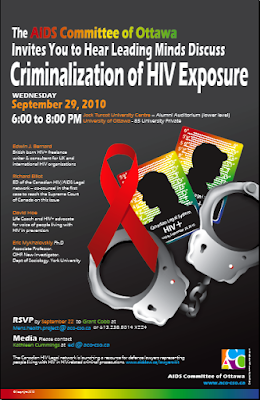

This Research Snapshot is from their report, “HIV Non-disclosure and the criminal law: Establishing policy options for Ontario,” which was funded by the Ontario HIV Treatment Network and involved a research collaboration between York University, Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, HIV and AIDS Legal Clinic (Ontario), Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention, AIDS Committee of Toronto, and Toronto PWA Foundation.