HIV: The share of women!

For the 8th of March, International Women’s Rights Day, Seronet takes stock of some figures on HIV related to women worldwide.

HIV in the world: women’s numbers

In 2015, globally, about 17.8 million women (aged 15 and over) were living with HIV, equivalent to 51% of the total population living with HIV. About 900,000 of the 1.9 million new HIV infections worldwide in 2015 – 47 percent – were women. It is young women and girls aged 15 to 24 who are particularly affected. Globally, about 2.3 million adolescent girls and young women were living with HIV in 2015, representing 60% of the entire population of young people (aged 15 to 24) living with HIV. 58% of new HIV infections among 15-24 year olds in 2015 were among adolescent girls and young women.

According to the same source, regional differences in new cases of HIV infection among young women and the proportion of women (aged 15 and over) living with HIV compared to men are considerable. They are even more important between young women (aged 15 to 24) and infected young men. In sub-Saharan Africa, 56% of new HIV infections occurred in women, and the rate was even higher among young women aged 15 to 24, accounting for 66% of new infections.

In the Caribbean, women accounted for 35% of newly infected adults, and 46% of new infections occurred among young women aged 15 to 24 years. In Eastern Europe and Central Asia, 31% of new cases of HIV infection have affected women; however, the rate of new infections among young women aged 15 to 24 reached 46%. In the Middle East and North Africa, women represent 38% of newly infected adults, while 48% of young women aged 15 to 24 are newly infected. In Western Europe, Central Europe and North America, 22% of new infections occurred in women, the highest rate among young women aged 15 to 24, with 29% of new infections (1).

Inequalities between women themselves

Some women are more exposed to HIV than others. This is a function of belonging to certain groups. The incidence of HIV in specific groups of women is disproportionate. According to an analysis of studies measuring the cumulative prevalence of HIV in 50 countries, it is estimated that sex workers around the world are about 14 times more likely to be infected with HIV than other women of childbearing age. (2). In addition, data from 30 countries indicate that the cumulative prevalence of HIV among women who inject drugs was 13%, compared to 9% among men who inject drugs (3).

A feminization of the HIV epidemic in France

Over the years, the HIV / AIDS epidemic has been strongly feminized in France too: the share of new diagnoses has increased in France from 13% in 1987 to 33% in 2009. Heterosexual contamination is the main vector of HIV transmission (54% of HIV-positive discoveries) and women make up the majority of these infections. Compared to men, they are infected younger.

In France, women account for about 30% of new HIV infections each year, a significant proportion of whom are born abroad and especially in sub-Saharan Africa. If we look at the 2016 data, we note that among heterosexuals, the majority of diagnostics relates to 2,300 people born abroad. 80% are born in sub-Saharan Africa and 63% are women. Late-stage discoveries are more specific to men than women.

Migrant women, in greater numbers than men in France, suffer more problems related to sexual health: complications specific to pregnancy and childbirth and sexual violence. These states are dependent on the conditions of the country of origin (sexual mutilation, forced marriages), and migration (rape, trafficking in human beings). They can be strengthened upon arrival in the host country, as the period of installation often corresponds to a period of health and social precariousness, which increases the risks of exposure to HIV and sexually transmitted infections.

What factors exacerbate the prevalence of HIV?

It’s obvious … but it’s worth remembering. Violence against women and girls increases their risk of HIV infection (4). A study in South Africa found that the link between intimate partner violence and HIV was more pronounced in the presence of domineering behaviour and high HIV prevalence.

In some settings, up to 45% of adolescent girls report that their first sexual experience was forced. Worldwide, more than 700 million women alive today were married before their eighteenth birthday. Often, they have limited access to prevention information and limited means to protect themselves from HIV infection. Worldwide, out of ten adolescent girls and young women aged 15 to 24, only three of them have complete and accurate knowledge of HIV (5). Lack of information on HIV prevention and the inability to use such information in the context of sexual relations, including in the context of marriage, undermine women’s ability to negotiate condom use and engage in safer sex, says UN Women.

Seropositivity: a double sentence for women

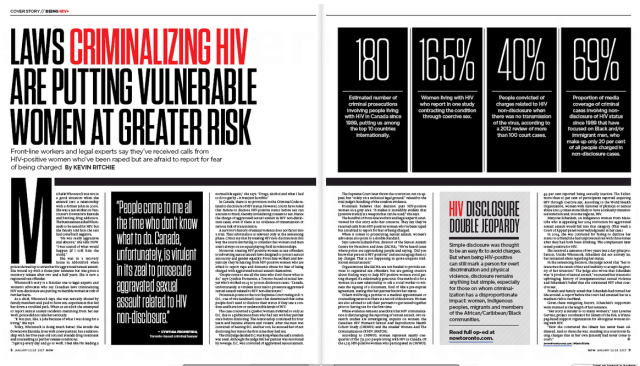

Other data indicate that women living with HIV are at increased risk of violence (6), including violations of their sexual and reproductive rights (reproductive health). Cases of involuntary or forced sterilization and forced abortions among women living with HIV have been reported in at least fourteen countries. In addition, legal standards directly affect the level of risk for women to contract HIV, says the UN Women. In many countries where women are most at risk, the laws that are supposed to protect them are ineffective. The lack of legal rights reinforces women’s subordinate status, particularly with regard to women’s rights to divorce, to possess and inherit property, to enter into contracts, to prosecute and to testify in court, to consent to medical treatment and open a bank account. Discriminatory laws on the criminalization of HIV transmission can also have a disproportionate impact on women, as they are more vulnerable to being tested for HIV and to find out whether or not they are infected with HIV when they access healthcare for their pregnancy. HIV-positive mothers are considered criminals under HIV-related laws in several countries in West and Central Africa, which explicitly or implicitly prohibits them from being pregnant or breastfeeding. for fear that they might transmit the virus to the fetus or to the child (7).

The response to HIV for women

Globally, between 76% and 77% of pregnant women have had access to antiretroviral drugs to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV, says UN Women (data for 2015). Despite this encouraging rate, more than half of the 21 priority countries of the UNAIDS Global Plan were unable to meet the need for family planning services for at least 25% of all married women. Another element is that governments are increasingly recognizing the importance of gender equality in HIV interventions at the national level. However, only 57% (out of the 104 countries that submitted data) had a specific budget. For their part, Global Fund expenditures on women and girls have increased from 42 percent of its total portfolio in 2013 to about 60 percent in 2015.

(1): UNAIDS, 2015 estimates from the AIDSinfo online database. Additional disaggregated data correspond to unpublished estimates provided by UNAIDS for 2015, derived from country-specific AIDS epidemic models.

(2) : Stefan Baral and al. (15 mars 2012), “Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis”, The Lancet Infectious Diseases, vol. 12, no 7. p. 542.

(3) : UNAIDS (2014) The Gap Report, p. 175.

(4) : R. Jewkes and al. (2006) « Factors Associated with HIV Sero-Status in Young Rural South African Women: Connections between Intimate Partner Violence and HIV », International Journal of Epidemiology, 35, p. 1461-1468 ;

(5) : UNAIDS (2015) 2015 Report on World AIDS Day “On the Fast-Track to end AIDS by 2030: Focus on Location and Population“, p. 75.

(6) : WHO and UNAIDS (2010) “Addressing violence against women and HIV/AIDS: What works?“, p. 33.

(7) : Commission mondiale sur le VIH et le droit (2012) « Risques, droit et santé », p. 23.

——————————————–

VIH : La part des femmes!

A l’occasion du 8 mars, Journée international des droits des femmes, Seronet fait le point sur quelques chiffres relatifs au VIH concernant les femmes dans le monde.

VIH dans le monde : la part des femmes

En 2015, à l’échelle mondiale, environ 17,8 millions de femmes (âgées de 15 ans et plus) vivaient avec le VIH, soit 51 % de toute la population vivant avec le VIH. Environ 900 000 des 1,9 million des nouveaux cas d’infection par le VIH constatés dans le monde en 2015 – soit 47 % – ont concerné des femmes. Ce sont les jeunes femmes et les adolescentes de 15 à 24 ans qui sont particulièrement touchées. A niveau mondial, environ 2,3 millions d’adolescentes et de jeunes femmes vivaient avec le VIH en 2015, représentant 60 % de toute la population de jeunes (de 15 à 24 ans) vivant avec le VIH. 58 % des nouveaux cas d’infection par le VIH chez les jeunes de 15 à 24 ans en 2015 touchaient des adolescentes et des jeunes femmes.

Selon la même source, les différences régionales concernant les nouveaux cas d’infection par le VIH chez les jeunes femmes et la proportion de femmes (âgées de 15 ans et plus) vivant avec le VIH par rapport aux hommes sont considérables. Elles sont encore plus importantes entre les jeunes femmes (âgées de 15 à 24 ans) et les jeunes hommes infectés. En Afrique subsaharienne, 56 % des nouveaux cas d’infection par le VIH ont touché des femmes, et ce taux a été encore plus élevé chez les jeunes femmes de 15 à 24 ans, représentant 66 % des nouveaux cas d’infection.

Dans les Caraïbes, les femmes ont représenté 35 % des adultes nouvellement infectés, et 46 % des nouveaux cas d’infections ont touché les jeunes femmes de 15 à 24 ans. En Europe de l’Est et en Asie centrale, 31 % des nouveaux cas d’infection par le VIH ont touché des femmes ; toutefois, le taux des nouveaux cas d’infection touchant les jeunes femmes de 15 à 24 ans a atteint 46 %. Au Moyen-Orient et en Afrique du Nord, les femmes représentent 38 % des adultes nouvellement infectés, alors que 48 % des jeunes femmes de 15 à 24 ans sont nouvellement infectées. En Europe occidentale, en Europe centrale et en Amérique du Nord, 22 % des nouveaux cas d’infection ont touché des femmes, ce taux étant plus élevé chez les jeunes femmes de 15 à 24 ans, avec 29 % de nouveaux cas d’infection (1).

Des inégalités entre les femmes elles-mêmes

Certaines femmes sont plus exposées au VIH que d’autres. C’est notamment fonction de l’appartenance à certaines groupes. L’incidence du VIH sur certains groupes spécifiques de femmes est disproportionnée. Selon une analyse d’études mesurant la prévalence cumulée du VIH dans 50 pays, on estime que, dans le monde, les travailleuses du sexe ont environ 14 fois plus de risques d’être infectées par le VIH que les autres femmes en âge de procréer (2). Par ailleurs, d’après des données émanant de 30 pays, la prévalence cumulée du VIH chez les femmes qui consomment des drogues injectables était de 13 %, contre 9 % chez les hommes qui consomment des drogues injectables (3).

Une féminisation de l’épidémie de VIH en France

Au fil des années, l’épidémie à VIH/sida s’est fortement féminisée en France aussi : la part de nouveaux diagnostics est passée, en France, de 13 % en 1987 à 33 % en 2009. La contamination hétérosexuelle est le principal vecteur de transmission du VIH (54 % des découvertes de séropositivité) et les femmes constituent la majorité de ces contaminations. Par rapport aux hommes, elles sont contaminées plus jeunes.

En France, les femmes représentent environ 30 % des nouvelles contaminations par le VIH chaque année, une part importante d’entre elles sont nées à l’étranger et en particulier en Afrique subsaharienne. Si on regarde les données de 2016, on note que les hétérosexuels, la majorité des découvertes de séropositivité est constituée par les 2 300 personnes nées à l’étranger. Il s’agit à 80 % de personnes nées en Afrique subsaharienne et à 63 % de femmes. Les découvertes à un stade avancé concernent plus particulièrement les hommes que les femmes.

Les femmes migrantes, en plus grand nombre que les hommes en France, subissent plus de problèmes liés à la santé sexuelle : complications propres à la grossesse et à l’accouchement, violences sexuelles. Ces états sont dépendants des conditions du pays d’origine (mutilations sexuelles, mariages forcés), et du parcours migratoire (viols, trafic d’êtres humains). Ils peuvent être renforcés à l’arrivée dans le pays d’accueil, la période d’installation correspondant souvent à une période de précarité sanitaire et sociale, qui accroît les risques d’exposition aux VIH et aux infections sexuellement transmissibles.

Quels facteurs exacerbent la prévalence du VIH ?

C’est une évidence… mais qu’il est bon de rappeler. La violence à l’égard des femmes et des filles augmente leurs risques d’infection par le VIH (4). Une étude menée en Afrique du Sud a démontré que le lien entre la violence infligée par un partenaire intime et le VIH était plus marqué en présence d’un comportement dominateur et d’une prévalence élevée du VIH.

Dans certains contextes, jusqu’à 45 % des adolescentes indiquent que leur première expérience sexuelle a été forcée. Dans le monde, plus de 700 millions de femmes en vie aujourd’hui ont été mariées avant leur dix-huitième anniversaire. Souvent, elles disposent d’un accès restreint aux informations de prévention, et de moyens limités pour se protéger contre une infection par le VIH. A l’échelle mondiale, sur dix adolescentes et jeunes femmes de 15 à 24 ans, seulement trois d’entre elles ont des connaissances complètes et exactes sur le VIH (5). Le manque d’informations sur la prévention du VIH et l’impossibilité d’utiliser de telles informations dans le cadre de relations sexuelles, y compris dans le contexte du mariage, compromettent la capacité des femmes à négocier le port d’un préservatif et à s’engager dans des pratiques sexuelles plus sûres, rappelle l’ONU Femmes.

La séropositivité : une double peine pour les femmes

D’autres données indiquent que les femmes vivant avec le VIH sont davantage exposées à des actes de violence (6), y compris des violations de leurs droits sexuels et génésiques (la santé reproductive). Des cas de stérilisation involontaire ou forcée et d’avortements forcés chez les femmes vivant avec le VIH ont été signalés dans au moins quatorze pays. De plus, les normes juridiques affectent directement le niveau de risque pour les femmes de contracter le VIH, rappelle l’Onu Femmes. Dans bon nombre de pays où les femmes y sont le plus exposées, les lois qui sont censées les protéger sont inefficaces. Le manque de droits juridiques renforce le statut de subordination des femmes, en particulier au regard des droits des femmes de divorcer, de posséder et d’hériter de biens, de conclure des contrats, de lancer des poursuites et de témoigner devant un tribunal, de consentir à un traitement médical et d’ouvrir un compte bancaire. Par ailleurs, les lois discriminatoires sur la criminalisation de la transmission du VIH peuvent avoir des répercussions disproportionnées sur les femmes, car elles sont plus exposées à être soumises à des tests de dépistage et ainsi à savoir si elles sont ou non infectées lors de soins au cours de la grossesse. Les mères séropositives sont considérées comme des criminelles en vertu de toutes les lois relatives au VIH en vigueur dans plusieurs pays en Afrique de l’Ouest et en Afrique centrale, ce qui leur interdit, explicitement ou implicitement, d’être enceintes ou d’allaiter, de crainte qu’elles transmettent le virus au fœtus ou à l’enfant (7).

La réponse face au VIH pour les femmes

A l’échelle mondiale, entre 76 et 77 % des femmes enceintes ont eu accès à des médicaments antirétroviraux pour prévenir la transmission du VIH de la mère à l’enfant, indique l’Onu Femmes (données pour 2015). Malgré ce taux encourageant, plus de la moitié des 21 pays prioritaires du Plan mondial d’Onusida ne parvenaient pas à répondre aux besoins en services de planning familial d’au moins 25 % de l’ensemble des femmes mariées. Autre élément : les gouvernements reconnaissent de plus en plus l’importance de l’égalité des sexes dans les interventions face au VIH qui sont menées à l’échelle nationale. Cependant, seulement 57 % (sur les 104 pays qui ont soumis des données) d’entre eux disposaient d’un budget spécifique. De leur côté, les dépenses du Fonds mondial de lutte contre le sida consacrées aux femmes et aux filles ont augmenté, passant de 42 % de son portefeuille total en 2013 à environ 60 % en 2015.

(1) : Onusida, estimations de 2015 provenant de la base de données en ligne AIDSinfo. Les données désagrégées supplémentaires correspondent aux estimations non publiées fournies par l’Onusida pour 2015, obtenues à partir de modèles des épidémies de sida spécifiques aux pays.

(2) : Stefan Baral et al. (15 mars 2012), “Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis”, The Lancet Infectious Diseases, vol. 12, no 7. p. 542.

(3) : Onusida (2014) The Gap Report, p. 175.

(4) : R. Jewkes et al. (2006) « Factors Associated with HIV Sero-Status in Young Rural South African Women: Connections between Intimate Partner Violence and HIV », International Journal of Epidemiology, 35, p. 1461-1468 ;

(5) : Onusida (2015) Rapport 2015 sur la Journée mondiale de lutte contre le sida “On the Fast-Track to end AIDS by 2030: Focus on Location and Population“, p. 75.

(6) : L’OMS et ONUSIDA (2010) “Addressing violence against women and HIV/AIDS: What works?“, p. 33.

(7) : Commission mondiale sur le VIH et le droit (2012) « Risques, droit et santé », p. 23.

Published in Seronet on March 7, 2018