Positive Life’s Communications and Policy Officer, Scott Harlum (pictured), explains why the organisation will advocate for changes to HIV disclosure requirements in the Public Health Act as part of the review.

The Public Health Act is a key piece of NSW legislation which impacts the lived experience of people living with HIV. For many years, Positive Life has advocated for a number of key changes to the Act to reflect the current reality of HIV as a chronic manageable health condition, to better support efforts to end HIV transmission and to acknowledge prevention of HIV transmission is a shared responsibility regardless of sero-status. With charges under the Crimes Act laid against a man relating to the alleged infection of another man in January, now unrelated accusations against a sex worker extradited to Western Australia, Positive Life will again advocate for change to the Public Health Act as part of a required review of the legislation.

Despite an update in 2010, Positive Life argues some sections of the Public Health Act need change, and even removal from the Act to protect the interests of people living with HIV, reduce stigma and discrimination and enhance HIV prevention and testing in the broader community. A key example is the removal of Section 79, known as the ‘disclosure provision’.

Section 79 requires anyone who knows they have a sexually transmissible infection (STI) including HIV to inform a person before they have sex, and for that person to voluntarily accept the risk of acquiring that infection. In NSW, if you are HIV-positive and don’t disclose your status before sex you are guilty of an offence under the Act. The requirement to disclose your HIV status before sex hasn’t changed from the 1991 version of the Act, except for the inclusion of a ‘reasonable precautions’ provision.

This provision provides a defence to prosecution if ‘reasonable precautions’ have been taken during sex to prevent transmission. However, the definition of ‘reasonable precautions’ remains unclear and this amendment falls short of the current reality of HIV. Removing Section 79 will provide a more comprehensive approach to the rights and responsibilities of the community regardless of sero-status.

With today’s HIV treatments, if a HIV-positive person is on treatments and has an ‘undetectable viral load’, the chances of condomless sex resulting in HIV infection are extremely low. However under the current Section 79, without change to the law or a court deciding that an undetectable viral load is a ‘reasonable precaution’, a person with HIV could still be committing an offence under the Act for not disclosing their status before sex.

Under Section 79, criminalising HIV discourages testing and encourages anonymous sex. Put simply, if you don’t know you have HIV you cannot be found guilty of an offence under the Act for not disclosing your status. Equally, anonymous sex reduces your chances of being identified for prosecution. In an era where more than 90% of people with HIV are on treatment and have an undetectable viral load, people who are infected with HIV but unaware of their status are more of a risk for transmission than people on treatment with a suppressed viral load.

Fear of prosecution inhibits honesty with sexual partners and medical providers, so Section 79 may actually increase the transmission of HIV and other STIs, rather than decrease it. An honest and open relationship with our doctor is crucial to maintain good health regardless of our sero-status. For example, contracting an STI such as gonorrhoea is a risk for anyone who is sexually active, and if the symptoms are hidden, we don’t know we’ve picked up an STI. If we can’t speak openly about the sex we have, it’s likely we won’t be tested for STIs and instead transmit any unknown infection to others.

Under Section 79, forced disclosure of our status as a person with HIV can encourage HIV-related stigma and discrimination, both real and perceived. Disclosure of our status as a person with HIV can, in rare circumstances, lead to violence. More often forced disclosure leads to rejection, loss of control over who knows of our status, discrimination on the basis of our status, or the premature ending of relationships.

Section 79 as it stands does not account for PrEP. Today, many HIV-negative people are already importing pre-exposure prophylaxis or ‘PrEP’, and following the announcement on World AIDS Day last year of an expanded trial of the HIV-prevention medication, many more will be taking PrEP as the trial is rolled out in coming months. A benefit of PrEP is it encourages HIV-negative people to take control of their own health and reduce their own risk of acquiring HIV. Reducing HIV transmission is a shared responsibility and Positive Life believes this principle should be reflected in the Public Health Act.

With the coming review of the Public Health Act, Positive Life will share more about other changes we believe should be made to the Act to reflect the modern reality of HIV as an ongoing manageable health condition. In the meantime, if you have questions or comments about our proposed changes to HIV disclosure requirements in the Act, please make contact on 1800 245 677 (freecall) or by email.

Originally published on Gay News Network

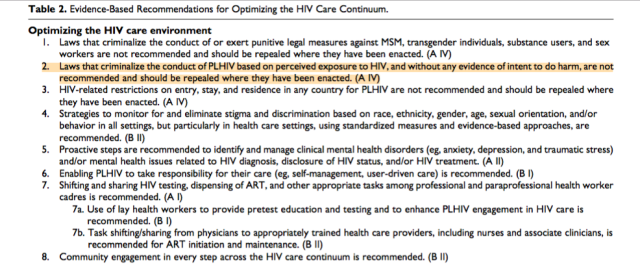

In many settings, optimizing the HIV care environment may be the most important action to ensure that there are meaningful increases in the number of people who are tested for HIV, linked to care, started on ART if diagnosed to be HIV positive, and assisted to achieve and maintain long-term viral suppression. Overcoming the legal, social, environmental, and structural barriers that limit access to the full range of services across the HIV care continuum requires multistakeholder engagement, diversified and inclusive strategies, and innovative approaches. Addressing laws that criminalize the conduct of key populations and supporting interventions that reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination are also critically important. People living with HIV also require support through peer counseling, education, and navigation mechanisms, and their self-management skills reinforced by strengthening HIV literacy across the continuum of care.

In many settings, optimizing the HIV care environment may be the most important action to ensure that there are meaningful increases in the number of people who are tested for HIV, linked to care, started on ART if diagnosed to be HIV positive, and assisted to achieve and maintain long-term viral suppression. Overcoming the legal, social, environmental, and structural barriers that limit access to the full range of services across the HIV care continuum requires multistakeholder engagement, diversified and inclusive strategies, and innovative approaches. Addressing laws that criminalize the conduct of key populations and supporting interventions that reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination are also critically important. People living with HIV also require support through peer counseling, education, and navigation mechanisms, and their self-management skills reinforced by strengthening HIV literacy across the continuum of care.