A new report released today shows that HIV criminalisation is a growing, global phenomenon. However, advocates around the world are working hard to ensure that the criminal law’s approach to people living with HIV fits with up-to-date science, as well as key legal and human rights principles.

Click on this link to read or download Advancing HIV Justice 2: Building momentum in global advocacy against HIV criminalisation.

What do we mean by ‘HIV criminalisation’?

HIV criminalisation describes the unjust application of the criminal law to people living with HIV based solely on their HIV status – either via HIV-specific criminal statutes, or by applying general criminal laws that allow for prosecution of unintentional HIV transmission, potential or perceived exposure to HIV where HIV was not transmitted, and/or non-disclosure of known HIV-positive status.

Such unjust application of the criminal law in relation to HIV is (i) not guided by the best available scientific and medical evidence relating to HIV, (ii) fails to uphold the principles of legal and judicial fairness (including key criminal law principles of legality, foreseeability, intent, causality, proportionality and proof), and (iii) infringes upon the human rights of those involved in criminal law cases.

What is the impact of HIV criminalisation?

Understanding the potential negative impact of HIV criminalisation on public health is critical to making informed policy decisions.

The last few years have seen increasing interest among researchers in the area of HIV criminalisation and a push into new areas of enquiry to examine the impacts of the unjust application of criminal law.

The report summarises a body of research which shows that instead of delivering a public health benefit, HIV criminalisation is a poor public health strategy, exacerbating racial and gender inequalities and negatively impacting a number of key areas including: testing; disclosure; sexual behaviour; and healthcare practice.

How many countries around the world have HIV criminalisation laws?

Since our last report, we found an increase in the number of countries that specifically allow for HIV criminalisation: these could be stand-alone HIV-specific criminal laws, part of omnibus HIV laws, or criminal and/or public health laws that specifically mention HIV.

Some of this increase is due to laws enacted since 2013 in Botswana, Cote d’lvoire, Nigeria, Uganda and Veracruz state (Mexico), and some is due to improved reporting and research methodology.

Our analysis shows that a total of 72 countries have adopted laws that specifically allow for HIV criminalisation, either because the law is HIV-specific, or because it names HIV as one (or more) of the diseases covered by the law. This total increases to 101 jurisdictions when the HIV criminalisation laws in 30 of the states that make up the United States are counted individually.

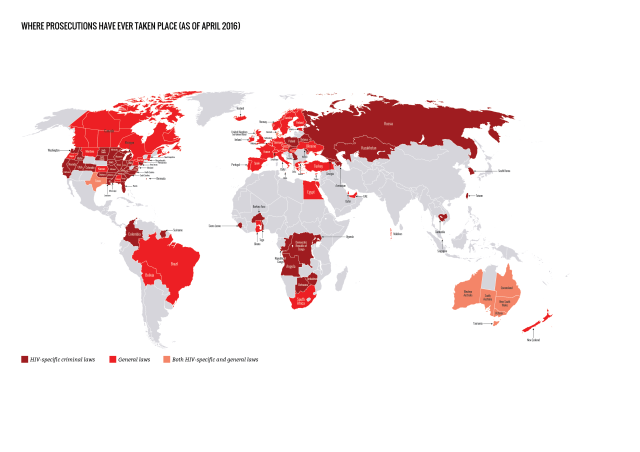

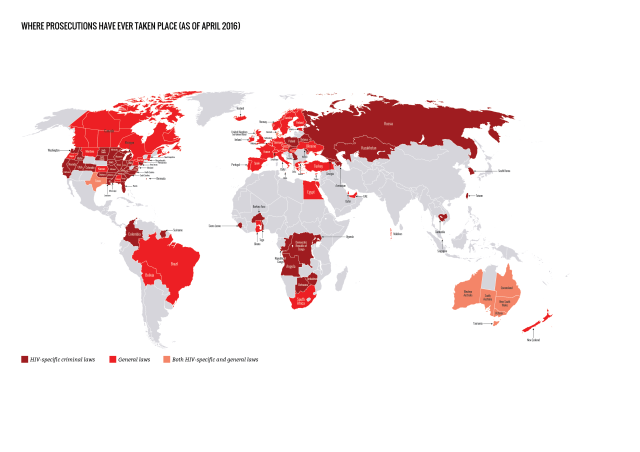

How many countries have prosecuted people living with HIV?

Prosecutions for HIV non-disclosure, potential or perceived exposure and/or unintentional transmission have now been reported in 61 countries. This total increases to 105 jurisdictions when individual US states and Australian states / territories are counted separately.

Of the 61 countries, 26 applied HIV criminalisation laws, 32 applied general criminal or public health laws, and three (Australia, Denmark and United States) applied both HIV criminalisation and general laws.

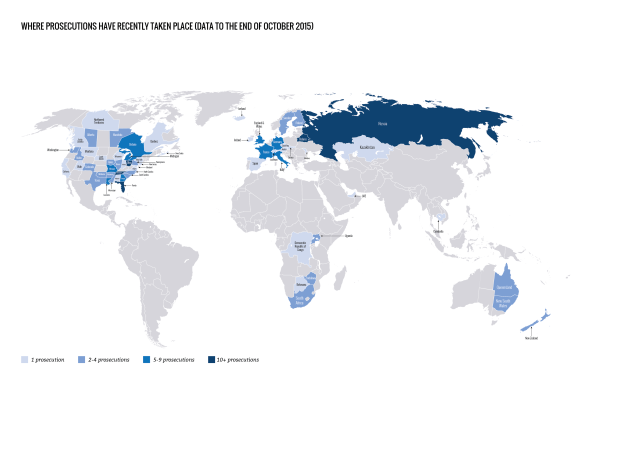

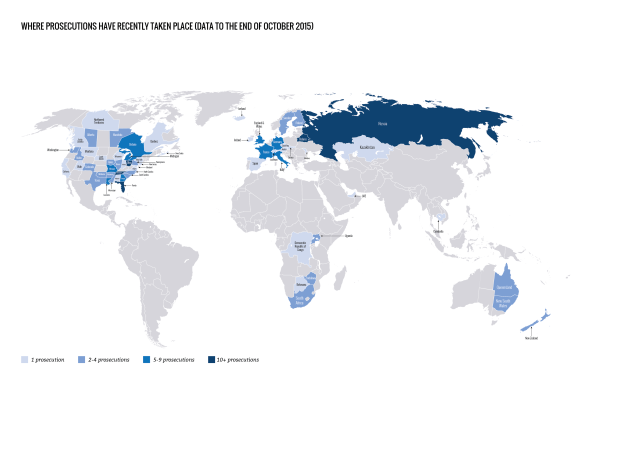

Where have prosecutions recently taken place?

We found reports of at least 313 arrests, prosecutions and/or convictions in 28 countries during the report period, covering 1 April 2013 to 30 September 2015.

Of note, we are now able to include data on reported prosecutions in Belarus and Russia, which are likely to have been taking place at least since the enactment of a Belarusian public health law in 1993 and a Russian HIV criminalisation law in 1995.

The highest number of cases during this period were reported in:

• Russia (at least 115) • United States (at least 104) • Belarus (at least 20) • Canada (at least 17) • France (at least 7) • United Kingdom (at least 6) • Italy (at least 6) • Australia (at least 5) • Germany (at least 5).

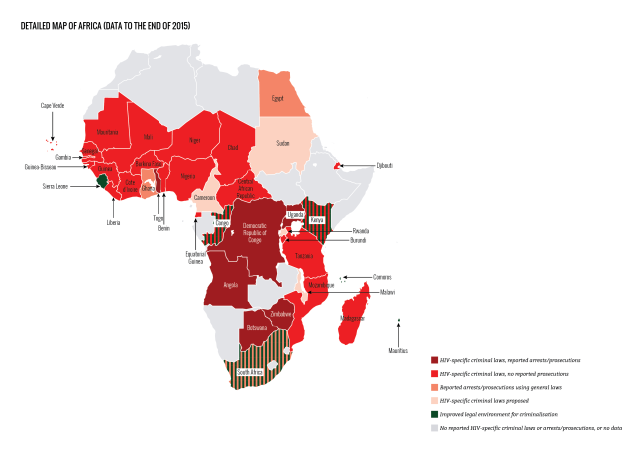

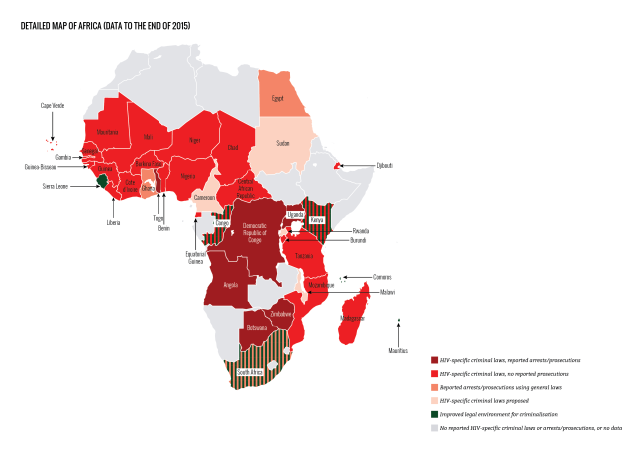

HIV criminalisation in sub-Sarahan Africa of increasing concern

Where there was no HIV criminalisation at the start of the 21st century, 30 sub-Saharan African countries have now enacted overly broad and/or vague HIV-specific criminal statutes.

Most of these statutes are part of omnibus HIV-specific laws that also include protective provisions, such as those relating to non-discrimination in employment, health and housing. However, they also include a number of problematic provisions such as compulsory HIV testing and involuntary partner notification, as well as HIV criminalisation.

During the period covered by this report four countries in sub-Saharan Africa passed new HIV criminalisation laws: Botswana, Cote d’lvoire, Nigeria and Uganda.

Very few countries in Africa are now unaffected by problematic HIV criminalisation laws. The rise of reported prosecutions in Africa during this period (in Botswana, South Africa, Uganda, and especially Zimbabwe), along with the continuing, growing number of HIV criminalisation laws on this continent, is especially alarming.

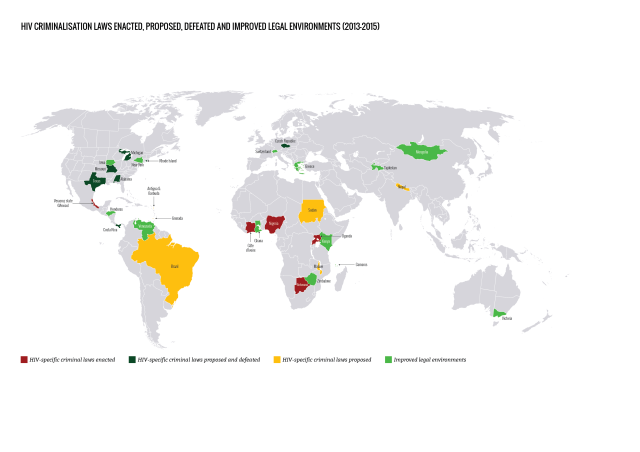

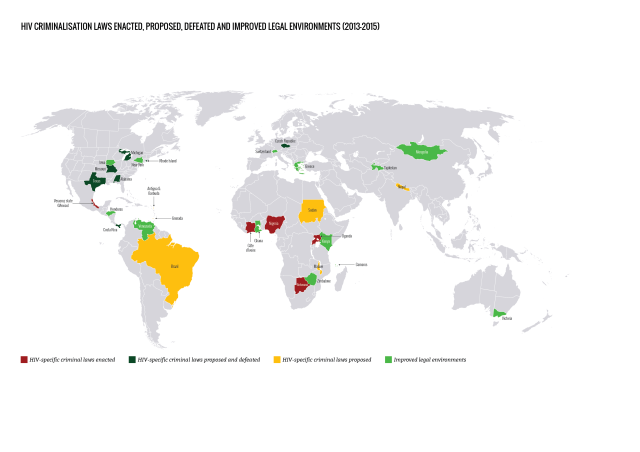

Where has advocacy improved legal environments?

Important and promising developments in case law, law reform and policy have taken place in many jurisdictions, most of which came about as a direct result of advocacy.

During the report period, although an additional 13 jurisdictions in nine countries proposed new HIV criminalisation laws, seven of these were not passed, primarily due to swift and effective advocacy against them at an early stage. Advocacy in another ten jurisdictions in seven countries challenged, improved or repealed HIV criminalisation laws.

The legal environment relating to HIV criminalisation has improved in a small number of countries in sub-Saharan Africa, most notably in Kenya. On 18 March 2015, Kenya’s High Court ruled that its HIV criminalisation provision – Section 24 of the HIV Prevention and Control Act 2006 – was unconstitutional because it was vague, overbroad and lacking in legal certainty, particularly in respect to the term ‘sexual contact’.

The Court also found it contravened Article 31 of the Kenyan Constitution which guarantees the right to privacy because the law created an obligation for people with HIV to disclose their status to their ‘sexual contacts’, with no corresponding obligation for recipients of such sensitive medical information to keep it confidential.

Using science as an advocacy tool

Increased knowledge about reduced infectiousness due to antiretroviral therapy has led to advocacy that resulted in a number of jurisdictions revising or revisiting their criminal laws or prosecutorial policies relating to HIV criminalisation, although progress has been frustratingly slow.

Following the ‘Swiss statement’, published in January 2008, a growing number of courts, government ministries and prosecutorial authorities have accepted antiretroviral therapy’s impact on reducing the risk of both HIV exposure and transmission.

However, scientific advances alone will neither ‘end AIDS’ nor end HIV criminalisation. Although the impact of antiretroviral therapy on infectiousness is an important advocacy tool, it must be remembered that many people with HIV do not have access to treatment (or are unable to achieve an undetectable viral load when on treatment) and that everyone has a right to choose not to know their status and/or start treatment and should not be stigmatised nor considered ‘second class citizens’ should they wish to delay diagnosis or antiretroviral therapy.

More work required

Despite the many incremental successes of the past few years, much more work is required to strengthen advocacy capacity. This is why a coalition of seven organisations launched HIV Justice Worldwide in April 2016.

We also need to be aware that HIV criminalisation does not exist in vacuum, and is often linked to punitive laws and policies that impact sexual and reproductive health and rights, especially those aimed at sex workers and/or men who have sex with men and other sexual minorities.

And, bearing in mind the stigma faced by those with, for example, hepatitis C and concerns over the sexual transmission of the Ebola and Zika viruses, as we move forward to eliminate – or modernise – HIV criminalisation laws, we must ensure that our work does not inadvertently lead to the further criminalisation of other communicable and/or sexually transmitted infections.

Click on this link to read or download Advancing HIV Justice 2: Building momentum in global advocacy against HIV criminalisation.

A note about the limitations of the data

The data and case analyses in this report covers a 30-month period, 1 April 2013 to 30 September 2015. This begins where the original Advancing HIV Justice report – which covered the 18-month period, 1 September 2011 to 31 March 2013 – left off. Our data should be seen as an illustration of what may be a more widespread, but generally undocumented, use of the criminal law against people with HIV.