Criminal Charges for HIV Non-disclosure, Exposure and Transmission: Legal Violence and the Lives of People Living with HIV

The following is an edited version of remarks presented by Alexander McClelland as part of ‘The Movement to End HIV Criminalization’ panel, held on September 15 2016 at Concordia University, Montreal, Canada.

Introduction

My work examines the relationship between the law, life and disease. I look at what takes place at the intersection of legal and medical knowledge, including what kinds of processes are deployed and enacted onto people as a result of that intersection. In relation to studying law and society, I examine law from a perspective that there is no absolute legal truth, but rather, that laws and who is understood as ‘criminal’ are developed over history and change based on social norms and contexts.

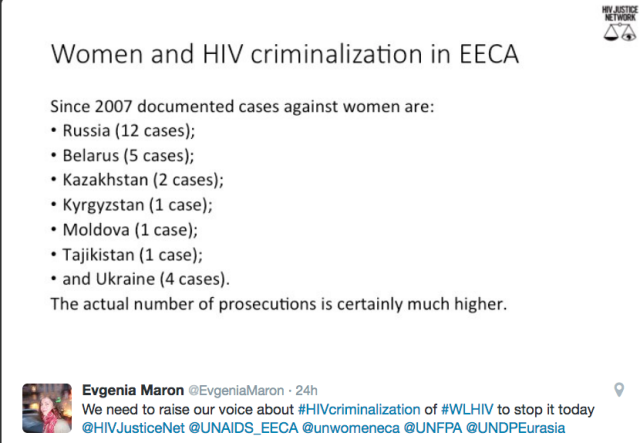

My research is examining the lived experiences of people who have been criminally charged in Canada in relation to HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission. As we know, Canada is a country recognized with having high rates of criminalization towards people living with HIV. Canada is one of the leading countries in the world to prosecute people with HIV who have not told a sex partner they are HIV-positive if that sex poses a ‘realistic possibility of transmission’, this is defined by the Supreme Court of Canada as sex without a condom and a low viral load combined. Under this application of the law people have been imprisoned when they were uninfectious due to HIV medications and when there was no transmission of HIV. It is estimated that there are approximately 180 cases that have taken place since 1989, when the first criminal charges were laid. And the trend indicates that the number of new cases is on the rise.

These approximately 180 cases have been applied asymmetrically and do not follow the epidemiological trends of the HIV epidemic, which if the law was objective, might be the case. Rather, through enumerating the cases with demographic data, social researchers have been able to reveal the biased racialized and gendered dimensions of this criminalization phenomenon. As a majority of those charged and prosecuted have been black men who have had sex with women.

Using a feminist form of sociological ethnographic inquiry[i], my approach has been to examine the impact of these laws on the people who they have targeted, from their own perspective. This kind of research aims to ensure that people do not become just objects to be studied, but are rather understood as people who are active agents. The premise of my work is to centrally place the experiences of people with HIV who have experienced criminalization first-hand so that efforts to address injustice and over-criminalization are directly informed by people’s lived realities.

I am a qualitative researcher and my work consists of archival research and a series of qualitative interviews. So far I have spoken with 14 people from across Canada. Through these interviews I aim to understand how being criminalized has materially shaped people’s lives. My research is still ongoing so what I am presenting is preliminary and still in process.

Every person I have spoken with who was charged criminally (12 of the 14) was charged with aggravated sexual assault, often more than once, along with a diverse range of other charges. Aggravated sexual assault is one of the harshest and most serious charges in the criminal code reserved for violent rapes involving a weapon, which can receive a sentence of life in prison. In the cases I looked at, the aggravating factor is understood by the courts to be HIV.

Living in a negative relation to the law

The people I have worked with live their lives in a negative relation to the law[ii] due to being labelled a ‘criminal’ and a ‘risk to public safety’ through being charged and/or prosecuted in relation to HIV non-disclosure, exposure or transmission. Living in a negative relation to the law means that one is rendered less of a person with codified rights, less of a person who is in need of protection from the law, and is rather regarded more as object of risk that legally constituted persons are to be protected from– protected from through forms of control, coercion and incapacitation. Being placed in a negative relation to the law is something that is enacted onto people of colour, people in poverty, people deemed deviant. This is a practice of extending the power of colonization, white supremacy, misogyny and homophobia, among others forms of marginalization and oppression.

People living with HIV today in Canada often live in a negative relation to the law just due to the fact that they are HIV-positive. We can very easily be placed in a tenuous relationship with our legally regarded personhood.

At its most severe, living with HIV in a negative relation to the law means your body can be disappeared by the state with impunity. Here I am thinking of the lives of H. Matthews and I. Williams.[iii]

Matthews, at 26 years old, a black man and newcomer to Canada, was convicted of 2 counts of aggravated sexual assault, one count of assault, and two other minor charges for not telling 4 women his HIV status before having sex with them. None of the women contracted HIV. He was sentenced to 40 months in prison. When he entered prison his CD4 count was 560. But while in prison he reported a series of health issues to the staff and in less than a year his CD4 count was 160 and he had lost 36 pounds. Despite seeing a number of medical experts, at no time over the course of his engagement with the criminal justice system was he put on any anti-HIV treatments despite being incarcerated because he potentially exposed others to HIV.

Matthews, at 26 years old, a black man and newcomer to Canada, was convicted of 2 counts of aggravated sexual assault, one count of assault, and two other minor charges for not telling 4 women his HIV status before having sex with them. None of the women contracted HIV. He was sentenced to 40 months in prison. When he entered prison his CD4 count was 560. But while in prison he reported a series of health issues to the staff and in less than a year his CD4 count was 160 and he had lost 36 pounds. Despite seeing a number of medical experts, at no time over the course of his engagement with the criminal justice system was he put on any anti-HIV treatments despite being incarcerated because he potentially exposed others to HIV.

Matthews died of AIDS on 12th of August 2007 in Central North Correctional Centre in Penetanguishene Ontario at 27 years old in a country in an era and country where, due to supposed access to life-saving medications, dying of AIDS has been increasingly rendered a rare occurrence, but where incarceration for HIV non-disclosure has been on the rise. There was an inquest into Matthews’ death, but in inquests into prison deaths in Canada, no one can be found culpable, and no one was held accountable for his death. The only reason information was released about his cause of death was because corrections staff were subpoenaed to testify at the inquest. Otherwise the ministry of corrections did not release any information about his death despite repeated requests from Matthews’s family and community organizations. A series of nine recommendations were made from the inquest to prevent future deaths, none of which have been implemented by the ministry of corrections. In the coroners report it indicated that he died of ‘natural causes’.

Another life that was disappeared was that of I. Williams, at 49 years old, who was first person sentenced after the Mabior Supreme Court decision in 2012. This was the second conviction for the father, who was sentenced to 4 years 9 months, which he served in Warkworth Institution in Ontario. As a Trinidad-born permanent resident, he would be deported after completion of his sentence. He pled guilty to charges of aggravated sexual assault. HIV was not transmitted to any of the women involved in the case. At the trial Williams stated he had been diagnosed with HIV in 1996, and had since been lonely and was been shunned by family and strangers alike soon as they learn of his status, as reported by the Toronto Star, he stated: ‘I feel very sorry for them people that I put that fear in them because I’m afraid, I’m afraid to be rejected, It is inhumane,’ he wept. ‘It’s very cruel,’ he said to the judge. He also told that court that convicting him and deporting him to Trinidad would be akin to a death sentence, because there he would not receive the health care he needs.

Another life that was disappeared was that of I. Williams, at 49 years old, who was first person sentenced after the Mabior Supreme Court decision in 2012. This was the second conviction for the father, who was sentenced to 4 years 9 months, which he served in Warkworth Institution in Ontario. As a Trinidad-born permanent resident, he would be deported after completion of his sentence. He pled guilty to charges of aggravated sexual assault. HIV was not transmitted to any of the women involved in the case. At the trial Williams stated he had been diagnosed with HIV in 1996, and had since been lonely and was been shunned by family and strangers alike soon as they learn of his status, as reported by the Toronto Star, he stated: ‘I feel very sorry for them people that I put that fear in them because I’m afraid, I’m afraid to be rejected, It is inhumane,’ he wept. ‘It’s very cruel,’ he said to the judge. He also told that court that convicting him and deporting him to Trinidad would be akin to a death sentence, because there he would not receive the health care he needs.

On October 1st 2013 Williams was reported as dead while in custody. Informal reports from people close to Williams indicated that he had been trying to get medical care for an injury for over six days before he was found dead due an untreated abscess on his leg. No details were released from Corrections, and there was no inquest into his death.

Amplification of penality: The compounding violence of HIV & criminal charges

Very plainly, living in a negative relation to the law in Canada when having HIV results in an amplification of penality. In Canada, the intersection of HIV and law in relation to non-disclosure, transmission and exposure makes possible a range of legal and bureaucratic punishments, including the most severe and harsh available, along with a range of interpersonal, casual forms of stigma, discrimination, punishment and violence. Understanding the different ways that violence manifests can help us understand the best course of action to call for accountability.

All of these types of punishment result in violence, violence that can be called legal violence.[iv] Legal violence being the forms of violence that are made possible once someone has engaged with the law. Examining the phenomena of HIV criminalization with the concept of legal violence can help us to understand the relationship between law and violence and how people become targets of violence because they are targets of the law.

The amplification of penality that manifests in these cases means that mechanisms usually reserved as exceptions can easily become the rule. Exceptions such as the police releasing a photo to the public before prosecution for reasons of ‘public safety’, denying people bail even if they have never been charged before and present themselves with their family as not being a flight risk, denying people a pre-trail assessment, being tried as an adult and being placed in an adult jail when under-age, placing people in solitary confinement for long periods of time for reasons of security, or labelling people with dangerous offender status (meaning someone can be confined indefinitely after a sentence is served). These exceptions can come to be the norm in cases of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission.

Guilty before proven innocent

The amplification of penality begins as soon as the charges are applied and does relate to a guilty verdict: People who are accused can be treated as guilty before proven innocent, and not the other way around.

For example, after being charged with one count of aggravated sexual assault, one indigenous man I spoke with was fired from his job due to being charged with rape and by having his HIV-positive status widely disclosed without his consent by people close to the woman who accused him. The man told to me that he had been in a relationship with the woman and had previously disclosed to her, when he broke up with her she went to the police. The aggravated sexual assault charge and loss of his job caused the man to have a mental breakdown. He then lost his housing and ended up living out of a McDonald’s bathroom. All of his friends turned against him, and he removed himself from social media due to the intense levels of daily harassment he faced online. The mark of just the accusation caused his entire reality to be drastically altered for the worse. He is still awaiting trial.

A white woman whom I spoke with attended a hotel party and blacked out at the party, where she was then gang-raped. She told me she did not have the capacity to disclose her HIV-positive status, as she was extremely intoxicated at the time of the assault against her. The next day she went to the police, who took a statement from her. The following day she was charged with multiple accounts of aggravated sexual assault. Her photograph, HIV-positive status and biometric details were widely distributed by the police, at which time multiple media articles were written about her. Because she had a history as a sex worker the articles painted her as a predator with HIV who was trying to spread HIV to others. Her privacy breached, her social life ruined. HIV was not transmitted to any of the men involved. She was prosecuted and ultimately served over 5 years in a corrections institution.

A black man I spoke with, after being called by the police about his charge of aggravated sexual assault, went to the police station to turn himself in. At the police station he was questioned without a lawyer present, and then was taken into a separate room and severely beaten by police. He was knocked unconscious and unaware of what had happened to him. Afterwards the police put him back in the questioning room and told him that nothing had happened and that he was fine. He is certain he was beaten due to having HIV and being charged with a rape charge. The accuser did not acquire HIV and the man mentioned that she tried to come back to him after initially calling the police. In his case, he ultimately appealed to the superior court in the province and his charges were stayed – meaning he was not found guilty. This was only after serving approx. four years in a combination of house arrest and prison.

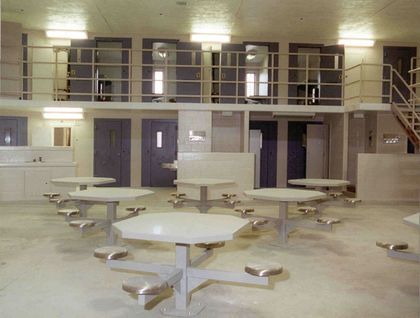

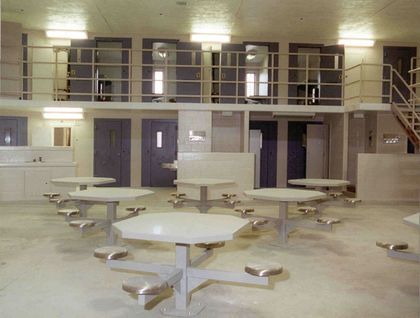

The violence of incarceration

The amplification of penality continues and becomes more formalized once someone is prosecuted. All people who are incarcerated in Canada are vulnerable to violence, but when HIV is introduced the vulnerabilities can be compounded.

A white man I spoke with who was prosecuted told me his ex-boyfriend called the police after the man disclosed to him. The man says he hadn’t disclosed his status previously, as he said he didn’t have the skills to do so. He also understood from his doctor that he was uninfectious as he had been on HIV medications. There was no allegation of HIV transmission. He had no previous criminal record and had never been in prison. One his first day inside prison, he was placed in general population, and was not given choice for protective custody.[v] During his first few days inside in general population, the man was surrounded on the range while using the phone to talk to his lawyer. The inmates who surrounded him asked the man what his charge was, saying he was lying and they knew he was a rapist with HIV. He was publicly beaten very severely by the inmates, all this in front of guard staff who didn’t intervene for a long period of time. Once the staff intervened, the man was then asked if they wanted to go into protective custody. He is certain that the staff leaked his charges and HIV-positive status to the men on his range, knowing he would then face physical violence. Eventually the man was placed in administrative segregation ‘for his own protection’. In administrative segregation he was stripped nude, only had a concrete floor, no bed, or blankets, and was given a just one sheet of paper and a pencil to occupy his 23.5 hours a day on lockdown. He served out the end of his sentence in those conditions. He is now suing corrections for his treatment by the guards.

An indigenous woman I spoke with was also placed into administrative segregation. She was sentenced to 2-years on charges of aggravated sexual assault. When incarcerated she was asked if she wanted to be by herself or in general population. She asked to be by herself – the conditions of which we not explained to her beforehand. This meant administrative segregation, which also included requirements for suicide watch. Under those conditions the woman was striped naked, placed in a cell with only a concert floor, a video camera watching her, and a window that a male guard would watch her through at all hours. She did not have access to her anti-anxiety or HIV medications.[vi] Eventually her lawyer got her released from these conditions and she is currently appealing her conviction.

An indigenous woman I spoke with was also placed into administrative segregation. She was sentenced to 2-years on charges of aggravated sexual assault. When incarcerated she was asked if she wanted to be by herself or in general population. She asked to be by herself – the conditions of which we not explained to her beforehand. This meant administrative segregation, which also included requirements for suicide watch. Under those conditions the woman was striped naked, placed in a cell with only a concert floor, a video camera watching her, and a window that a male guard would watch her through at all hours. She did not have access to her anti-anxiety or HIV medications.[vi] Eventually her lawyer got her released from these conditions and she is currently appealing her conviction.

A Métis man who I spoke with, who was serving a 5.5-year sentence in protective custody, while inside got very serious bacterial infection is his genital area. The infection persisted for over a month during which time he made repeated requests to see a doctor, which were delayed or denied. At one point a guard whom had previously let the man know that he was aware of his HIV-positive status, took the man’s written request to access the doctor and ripped it up on front of the man and threw it in the trash. It was not until the situation nearly threatened the man’s life that he was taken to the doctor for the emergency – this was months after the initial request by the man. This story becomes even more disturbing when we remember the deaths of Williams and Matthews.

The mark of criminality in daily life: Stigma & ongoing surveillance

The impact of penality extends well beyond prosecution, if there is a prosecution. A white man who I spoke with was under house arrest for over 3-years. His charges were ultimately stayed, as his case only involved a ‘blowjob’ and the Crown prosecutor was likely to lose at trial. No HIV transmission was alleged in the case. Under house arrest, he was to live in the houses of different sureties. He was reliant on the surety, couldn’t work, or go to school, and was severely isolated. Once the charges were stayed, he went to find his own housing. His case had been in the media, and despite the charge being stayed, his and his name when searched in Google revealed details about his HIV-positive status and the aggravated sexual assault charges. When applying for one apartment, he got a call back, and the landlord asked him to come back to visit the place, a good sign he thought. When he showed up the landlord opened the door and yelled at the man ‘I don’t rent to rapists’ and then pushed the man down the flight of stairs to the home. The man has also been denied jobs for the same reason.

In regards to extending penality beyond a prosecution, seven of the people I have spoken with are now registered sex offenders. The registry is a mechanism for continued police surveillance after prison release. A number of these people prior to incarceration used to work in professions that require background checks, which would now turn up badly due to the criminal record and Sex Offender Registry listing. One woman I spoke with used to do childcare for her job, and as a result of being on the registry she cannot get the job she used to have. This is also the case with others, which means they live of social assistance support even though they want to work. The result of their prosecution continues to extend into their daily lives today through threatening their economic security.

As a result of their experiences, every person I have interviewed has noted that they have either tried to commit suicide, or has had periods of regular suicidal ideation. Today, a majority of the people I spoke with live with post-traumatic stress disorder, which has a wide range of impacts on their daily lives. All of them also now have a complex and strained relationship with society. Many are very angry at society, a society, which took their personhood away and has treated them as less than human.

Bearing witness to call for action

All of this violence enacted towards them because of a supposed ‘crime’ that is entirely non-violent, and in which the notion of harm is an ideological one rooted in HIV-related stigma and AIDS-phobia. A crime where proving the intent to harm is extremely difficult, but due to fear and out-dated notions of AIDS as infectious and deadly, proving intent has been replaced by the fact that someone just has HIV. In many cases those who were charged and/or prosecuted explained to me that they understood that they took steps to protect their partners, such as using condoms, or regular taking medications so that they would be rendered uninfectious. What does it say about our society that the criminal justice system we have employs its most punitive functions towards people who have done no violence except perhaps that they have not told someone else that they have a medically controllable chronic disease?

Revealing these forms of legal violence is part of a deliberate political project – forms of violence that are simultaneously institutional and interpersonal, and both physical and psychological. These forms of violence are often obscured through bureaucracy, and forms of marginalization because the people onto whom these forms of violence are enacted have been deemed unworthy of living as legally safeguarded persons. These forms of violence are rooted in stigma and a fear of the ‘other’. These forms of violence are an extension of white supremacy, homophobia, colonization and misogyny. Many of the people I have spoken with live in poverty and are racialized. Women I have spoken with have been assaulted, but they are the ones who are criminally charged. Through revealing these forms of legal violence I hope we will be better positioned to deem thus situation unacceptable. To bear witness so we can call for action. Our work on this issue should be an act of refusal, a refusal to accept this current situation and a refusal to let these lives be rendered disposable by institutions of the state.

People living with HIV are a people who are over-policed but are under-protected. We live under heightened state and community surveillance due to criminalization. But we are provided limited protections when we call for help. We are deemed unworthy of care and support, unless that support is instrumental in helping us not transmit HIV to others. Despite all of this, all of the people I have spoken with for my project are passionate, kind, funny, charming and dynamic people. People with a visions for the future, and who wanted to share their stories for this project as an act of healing, as a way to seek justice, and as a way to turn what happened to them into a positive force for change.

Alexander McClelland is a researcher who is currently working on a doctorate at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies on Culture and Society, Concordia University. His work is supported through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Concordia University.

Endnotes

[i] See: Smith, Dorothy. E. (2005). Institutional Ethnography: A Sociology for People. Toronto: AltaMira Press.

[ii] Existing in a negative relation to the law means people who are institutionally marked as criminals, who are then rendered civilly and socially dead under legal regimes, people who through being labelled a criminal are deemed worthy of being dehumanized through forms of state institutional punishment. I draw on this notion he living in a negative relation to the law as elaborated through the work of Colin developed in the work of Colin Dayan (see: Dayan, Colin. 2011. The Law is a White Dog: How Legal Rituals Make and Unmake Persons. Princeton University Press: Princeton).

[iii] I have provided some privacy through not indicating full names.

[iv] Legal violence helps us examine Including how law makes possible forms of violence through forms of legal interpretation, incarceration, and sentencing, which are acts of violence through taking one’s legal personhood away. The violent actions made possible by the law are also often themselves deemed illegal. But because legal violence is often targeted towards people whose legal personhood has been deconstituted, the illegality of these forms of violence can go unrecognized or unquestioned. This concept has been elaborated in the work of Robert Cover (see: Cover, Robert. 1986. Violence and the Word. The Yale Law Journal, 95, 1601-1629.)

[v] It is required that someone be given the choice to go into protective custody, especially if the person has a charge such as aggravated sexual assault, know as a “dirty charge” inside prison, where you would go into protective custody to avoid violence from other inmates.

[vi] It should also be noted that all of the people who I spoke with that were incarcerated had numerous difficulties in accessing their HIV medications – despite being incarcerated for having HIV, in a country where being detectable can result in a crime, people with HIV who are incarcerated have a very hard time accessing their HIV medications due to a range of bureaucratic, logistical and punitive barriers