This playlist contains recordings of a training for lawyers on strategic litigation, legal defense and advocacy on HIV and TB justice from 20-23 February 2018 in Johannesburg, South Africa by the Southern Africa Litigation Centre (SALC), HIV Justice Worldwide, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), the Stop TB Partnership, the AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa (ARASA), and the Kenya Legal & Ethical Issues Network on HIV and AIDS (KELIN). The training was funded under the Africa Regional Grant on HIV: Removing Legal Barriers. Resources and more information on the training are available here: http://www.southernafricalitigationce… With thanks to Nicholas Feustel of Georgetown Media.

Webinar: PWN-USA HIV Criminalization First Responders Series: Activating Support Networks (PWN-USA, 2018)

The second webinar in the First Responder series focuses on activating support networks for people experiencing HIV criminalization. This webinar covers how to work with local coalitions and organizations, how to create fundraising campaigns, and how to create social support systems that keep people living with HIV who are incarcerated connected to their communities and community resources.

Estonia: Partners should share responsibility for their own health

Known in Estonia, as a fighter against the spread of the AIDS epidemic, Dr Nelli Kalikova, believes that a man convicted to four years in prison for sexually transmitting HIV to a woman with HIV virus is no more to blame than the woman herself.

She told this to journalist Arthur Tooman in an online interview for rus.err.ee, whose full record can be viewed on the video.

In October, a verdict was pronounced against a 34-year-old man who was found guilty that, despite knowing about his HIV diagnosis, he had sex with women and infected at least one partner with HIV. The court decision resonated when a doctor who actively engaged in HIV and AIDS issues in Estonia, Nelly Kalikova, founder of the AIDS-i Tugikeskus AIDS Support Center, contacted the media for him.

“Yes, he made a mistake, but he received a punishment, as for an unintentional murder – these things are not comparable.”

Kalikova agrees that a punishment should have followed, but it could be in the form of monetary compensation for moral damage or conditional punishment. “It brings up not the severity of punishment, but its inevitability, because the criminals are born of the realization that they will never be punished,” Kalikova is sure.

The doctor believes that women who had sexual intercourse with this man should take care of themselves and use protection – if they did not do so, then they should share responsibility for what happened with their partner 50/50.

“Yes, he could have prevented this from happening, but he did not do it, and women had to be protected.” You do not have to jump into a cot without a condom, unless it’s your regular partner. “They’re not the poor lambs that the media represent, they had to think”.

Infected unintentionally, it was just negligence

Kalikova believes that it is wrong to say that the young man infected his partner intentionally. As well as to say that he infected them. “Intentionally, in this situation, this is when a person genuinely wants other people to have his ailment, this is the so-called AIDS-terrorism, in history such people are known, but this case is not one of them,” says the experienced doctor. In her opinion, it is simply a matter of frivolity and carelessness.

“Perhaps he reads a lot – and in recent scientific articles it is said that the percentage of HIV infection during sexual intercourse is not very large – about 0.4%,” Kalikova adds.

“The lesson for HIV-positive people from this whole story is that they will always be in danger,” Kalikova said, “They can always be handed in for nothing.” All the evidence is zero. “As the woman said, they believed her that way. it’s bad, “Nelly Kalikova said,” Women who do not use condoms do not take any responsibility for themselves and for society. ”

When asked by a journalist whether HIV-positive people should warn their partners about the disease, Kalikova replied that it is not necessary to do this if a condom is used.

In addition, she believes that such confessions frightesn off partners, that it, in fact deprives the infected from the opportunity to create any close relationship. “There are only rare cases when there is a lot of love and for the sake of a relationship the partner is ready for anything,” Kalikova said.

If it breaks, the risk is great, and the partner must have the right to choose whether to take risks or not,” the journalist retorted.

“If we demand 100% of the recognition of our disease in HIV-positive people, we will put an end to the sexual life of all such people.” Of the 20 partners to whom an infected person makes a confession, he will at best have one. ”

“Let a person have a sexual life, and others should be responsible for their own health” – summed up the point of view of Kalikova Arthur Tooman. And the guest agreed with this opinion.

Kalikova also does not take responsibility for himself

In the article Õhtuleht Nelly Kalikova accuses the media, police, court, doctors, centers for working with HIV-infected people in misconduct in relation to this case. During the interview for rus.err.ee it was found out that, at the same time, she does not relieve herself of responsibility.

“Yes, if we lived in a world where the students 100% follow the behests of the teacher, our society would be different, but that’s not so.”

According to Kalikova, in a street poll of 20-year-olds on how to protect themselves from AIDS, 99% will answer the question correctly. They are informed. But the question of using a condom with the last sexual contact is positively answered only by 50%. “This suggests that people are informed, but not motivated – the reasons for this may be different,” the doctor’s statistics show.

Estonian society is immature in relation to HIV-infected people

Speaking of the response to her article-opinion in Õhtuleht, Kalikova points out that the rhetoric of comments is the rhetoric of an immature society in matters of HIV.

HIV emerged in the early 1980s in the United States – horrible discrimination against HIV-infected was occurring. Then the society began to gradually understand that this is a disease, and now in the West the society is at a fairly tolerant level. Estonia is still 15 years old.

Punished disproportionate to the crime

Kalikova certainly recognizes that the young man has committed a crime and should be punished, but she does not agree with the manner in which justice was administered over him and how severe the sentence was.

“Everything was done in a non-human way, and in this case the girl received nothing except hassle and shame, and if she had been awarded monetary compensation for moral damage, then all parties would win.”

Нелли Каликова: заразивший ВИЧ женщину мужчина виноват лишь на 50%

Известный в Эстонии борец с распространением эпидемии СПИДа, врач Нелли Каликова, считает, что осужденный на четыре года тюрьмы за заражение половым путем женщины вирусом ВИЧ мужчина виноват не более, чем сама эта женщина.

Об этом она сказала журналисту Артуру Тооману в онлайн-интервью для rus.err.ee, полную запись которого можно посмотреть на видео.

В октябре был оглашен приговор в отношении 34-летнего мужчины, которого признали виновным в том, что, зная о своем диагнозе ВИЧ, он вступал в половые связи с женщинами и заразил по крайней мере одну партнершу ВИЧ-инфекцией. Судебное решение получило резонанс, когда в СМИ за него вступилась врач, активно занимающаяся в Эстонии проблемами ВИЧ и СПИДа, учредитель центра поддержки в борьбе со СПИД-ом AIDS-i Tugikeskus Нелли Каликова.

“Да, он совершил ошибку, но наказание получил, как за непредумышленное убийство – эти вещи несравнимы”.

Каликова согласна, что наказание должно было последовать, но оно могло бы быть в виде денежной компенсации морального ущерба или условного наказания. “Воспитывает не суровость наказания, а его неотвратимость, потому что преступников плодит осознание того, что их никогда не накажут”, – уверена Каликова.

Врач считает, что женщины, вступившие в половую связь с этим мужчиной, должны были сами позаботиться о своем здоровье и использовать защиту – раз они этого не сделали, то ответственность за случившееся они должны разделить со своим партнером 50/50.

“Да, он мог предотвратить случившееся, но этого не сделал, а женщины были обязаны предохраняться. Не надо прыгать в койку без презерватива, если это не твой постоянный партнер. Они далеко не бедные овечки, какими их представляют СМИ. Они должны были думать”

Заражал ненамеренно, это была просто халатность

Каликова считает, что говорить о том, что молодой человек заражал своих партнерш намеренно – неправильно. Так же, как и утверждать, что именно он их заразил. “Намеренно, в данной ситуации – это когда человек искренне желает, чтобы его недугом обзавелись и другие. Это так называемый СПИД-терроризм, в истории такие люди известны, но данный случай – не такой”, – говорит опытный врач. По ее мнению, речь идет просто о легкомысленном и халатном отношении.

“Возможно, он много читал – а в последних научных статьях говорится о том, что процент заражения ВИЧ при половом контакте не очень велик – около 0,4%”, – добавляет Каликова.

“Ату его, ату!”

“Урок для ВИЧ-позитивных из всей этой истории – тот , что они всегда будут по жизни в опасности, – уверена Каликова, – Их всегда могут сдать ни за что. Все доказательства – нулевые. Как женщина сказала, так ей и поверили. И это плохо! – считает Нелли Каликова. – Женщины, не использующие презервативы, не несут никакой ответственности перед собой и перед обществом”.

На вопрос журналиста, должны ли ВИЧ-инфицированные предупреждать своих партнеров о недуге, Каликова ответила, что это делать не обязательно, если используется перезерватив.

Кроме того, она считает, что подобные признания отпугивают партнеров, то есть фактически лишают инфицированных возможности создать какие-либо близкие отношения. “Бывают лишь редкие случаи, когда случается большая любовь и ради отношений партнер готов на все”, – говорит Каликова.

А если он порвется. Риск большой. И право на выбор – рисковать или нет – партнер должен иметь”, – парировал журналист.

“Если мы будем требовать в 100% случаях признания своего заболевания у ВИЧ-инфицированных, то мы поставим крест на сексуальной жизни всех таких людей. Из 20 партнеров, которым инфицированный сделает признание, у него в лучшем случае останется один”.

“Пусть у человека будет сексуальная жизнь, а другие пусть несут ответственность за свое здоровье сами?” – подытожил точку зрения Каликовой Артур Тооман. И гостья согласилась с этим мнением.

С себя ответственности Каликова тоже не снимает

В статье Õhtuleht Нелли Каликова обвиняет СМИ, полицию, суд, врачей, центры по работе с ВИЧ-инфицированными в неправильном поведении применительно к данному случаю. В ходе интервью для rus.err.ee выяснилось, чтоо при этом она не снимает ответственности и с себя.

“Да, если бы мы жили в мире, где ученики 100%-но следуют заветам учителя, то наше общество было бы другим. Но это не так”.

По словам Каликовой, при уличном опросе 20-летних на тему, как уберечься от СПИДа, 99% ответят на вопрос правильно. Они информированы. Но на вопрос об использовании презерватива при последнем половом контакте положительно ответит только 50%. “Это говорит о том, что люди проинформированы, но не мотивированы – причины этому могут быть разные”, – приводит статистику исследований врач.

Эстонское общество незрело в отношении к ВИЧ-инфицированным

Говоря об отклике на ее статью-мнение в Õhtuleht, Каликова указывает на то, что риторика комментариев – это риторика незрелого общества в вопросах ВИЧ.

ВИЧ появился в начале 1980-х в США – творилась ужасная дискриминация в отношении ВИЧ-инфицированных. Затем общество начало постепенно понимать, что это болезнь, и сейчас на западе общество находится на достаточно толерантном уровне. Эстонии до него еще идти лет 15.

Наказан непропорционально преступлению

Каликова безусловно признает, что молодой человек совершил преступление и должен быть наказан, но она не согласна с тем, каким образом над ним вершилось правосудие и насколько суров был приговор.

“Все было сделано не по-людски. Да и девушка в этом случае ничего не получила, кроме нервотрепки и позора. А если бы ему присудили денежную компенсацию морального ущерба, то выиграли бы все стороны”.

Africa: Moving towards revolutionising approaches to HIV criminalisation

“We have all agreed with the Sustainable Development Goal of ending HIV and Tuberculosis by 2030. We cannot get there while we are arresting the same people we are supposed to ensure are accessing treatment and living positively,” said Dr Ruth Labode, a member of Parliament from Zimbabwe opening remarks at a two-day global meeting co-hosted by the AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa (ARASA) and HIV Justice Worldwide (HJWW) on 24 and 25 April 2017 in Johannesburg, South Africa, which focused on “Revolutionising approaches to Criminalisation of HIV Non-disclosure, Exposure and Transmission”.

The meeting was attended by advocates, civil society organisations, lawyers, judges, national human rights institutions and Members of Parliament from all over Africa and with some delegates from North America. Central to these deliberations was the draconian provisions within numerous HIV-specific laws being developed as government responses to the prevention and control of the HIV epidemic. The good intentions inherent in these pieces of legislation are often marred with provisions, which criminalise people based on their HIV status. Punitive provisions relating to ‘compulsory testing’, ‘involuntary partner notification’, ‘non-disclosure’ and ‘transmission’ of HIV are often cited, fueling stigma against people living with HIV.

The common theme binding these deliberations, was the negative impact of HIV criminalisation and the stories that were shared by colleagues. The increasing trend of imposing criminal sanctions against people living with HIV, had resulted in adverse impact on public health outcomes for certain populations, especially women. While reinforcing stigma, HIV criminalisation impedes access to sexual and reproductive health services such as condoms, HIV testing and treatment. Further, HIV criminalisation discourages HIV-positive women from accessing ante-natal care, which leads to increased maternal and child mortality. The overly broad and vague nature of most HIV specific laws, accompanied by the imposition of criminal sanctions without empirical or scientific support, further underpins the rift between public health goals and the protection of human rights.

Representing the AIDS Legal Network, one of the partners who led the development of the 10 Reasons Why Criminalisation Harms Women, Johanna Kehler mentioned the fact that, “HIV criminalisation and HIV specific laws are often set against a social milieu that is patriarchal, heteronormative and perpetuates gender inequalities and utilises punitive approaches to “correct” imbalances.” She went on to add that these laws ultimately maintain and widen the divide between public health needs and human rights obligations.

“Most prosecutions globally involve no or negligible risk of transmission. Among the thousands of known prosecutions, cases where it was clear, much less proven beyond reasonable doubt, that an individual planned on or wanted to infect another person with HIV, are exceedingly rare. People are being convicted of crimes contrary to the best public health advice, but also contrary to scientific and medical evidence”, said Dr Laurel Sprague of the HIV Justice Network, who has since become the Executive Director of the Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+).

“Most prosecutions globally involve no or negligible risk of transmission. Among the thousands of known prosecutions, cases where it was clear, much less proven beyond reasonable doubt, that an individual planned on or wanted to infect another person with HIV, are exceedingly rare. People are being convicted of crimes contrary to the best public health advice, but also contrary to scientific and medical evidence”, said Dr Laurel Sprague of the HIV Justice Network, who has since become the Executive Director of the Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+).

During the meeting, various organisations shared their experiences around litigating these matters and community advocacy mounted to reform problematic laws or specific draconian provisions. Cases from Zimbabwe, Nigeria and Niger showcased that challenges were experiences in most contexts.

The Uganda Network on Law, Ethics & HIV/AIDS (UGANET), together with other advocates and activists, continue to challenge the Ugandan law and constitutionality of the criminalisation provisions contained in the HIV Prevention and Control Act of 2014. The Southern Africa Litigation Centre (SALC) spoke to the extensive work that they furthered in Malawi, which included a focus on arbitrary arrests and dentition. Malawi has taken the centre stage where HIV criminalisation is concerned, as they are currently in the process of tabling a decade-old Draft HIV and AIDS (Prevention and Management) Bill, which contains draconian provisions around HIV criminalisation.

Amplifying the voice of survivors of HIV criminalisation, the meeting was privileged to engage with Kerry Thomas via telephone from a state correctional facility in Boise, Idaho in the United States of America. Mr Thomas, who was prosecuted for HIV non-disclosure and the sentence that he is serving, reinforced the unjust nature of these laws. Mr Thomas is currently serving his eighth year out of a 30-year sentence for non- disclosure to his ex-partner, despite there being no proof of transmission and the fact that he had consensual and protected sex. His appeal on the unconstitutionality of Idaho’s non-disclosure law, was overturned in the District courts in 2016.

The meeting concluded with very strong calls for everyone to joining the global HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE movement and organisations committed to utilise their existing resources to galvanise advocacy focusing on ending HIV criminalisation.

Participants agreed that there was a need to focus on the inter-sectionalities within the HIV criminalisation discourse, as well as a need for coordination and collaboration amongst legislators, members of the judiciary, parliamentarians, health care workers and civil society organisations to further advocacy related to this issue.

The participants also agreed that transformative approaches to HIV criminalisation, require both legal and social reforms, such as sensitisation of community members and the media. ARASA has committed to working with colleagues in developing a timeline of key events and advocacy opportunities, at which colleagues could participate.

Revolutionising approaches to Criminalisation of HIV Non-disclosure, Exposure and Transmission was supported by a grant from the Robert Carr civil society networks Fund.

Since its inception, ARASA has played an active role in addressing HIV criminalisation in the region and globally. ARASA has strengthened the capacity of civil society on the issue and supported partners to work with the media, parliamentarians, members of the judiciary and lawyers to address HIV criminalisation.

To read more about the meeting, follow #Decrim4Health on Facebook and Twitter. You can also view a gallery of photos taken during the meeting here.

US: Rolling Stone magazine covers HIV criminalisation and life as a person living with HIV in the US armed forces

What It’s Like to Be HIV Positive in the Military

Soldiers can be prosecuted for having sex, latest medications aren’t widely available – are the armed forces living in the 1980s when it comes to AIDS?

There’s not much to see in Otisville, New York. The town, with a population of just over 1,000 people, looks like an old mining village with white-painted ranch homes tucked behind the terrain’s rolling hills. The town is on the tip of Orange County, about 60 miles northwest of New York City; turn left down I-209 and you’ll pull into New Jersey, turn right and you’re in Pennsylvania.

For Kenneth Pinkela, Otisville dates back four generations with his family. The old Railroad Hotel and Bar off Main Street – one of the town’s three major roads – is the one his grandfather owned.

“Not a lot to look at, but it’s where I was raised. It’s home,” says Pinkela, driving his Ford pickup through the winding streets.

For Pinkela, Otisville is bittersweet. At 50 years old, the former Army lieutenant colonel, who still holds the shape of a weightlifter, is stuck there. He was forced to move back into his parent’s home three years ago after a military court martial had found him guilty of aggravated assault and battery back in 2012.

But Pinkela never bruised up anyone. Instead, he was tried and charged for exposing a younger lieutenant to HIV, though there was no proof of transmission. Pinkela has been HIV positive since 2007 when he was diagnosed right before deployment to Iraq during the surge.

President Jimmy Carter denounced Pinkela’s trial, and advocates argue it was one of the last Don’t Ask Don’t Tell cases the military tried and won. (Pinkela is also openly gay.) He served eight months in prison, lost his home and was dishonorably discharged from the Army.

Otisville was the only place for Pinkela to retreat to – specifically, back to his mother’s house.

Since being home, things have only gotten worse for Pinkela. His relationship with his mother is strained, he hasn’t had sex for years and doesn’t feel safe in public places.

“The post-traumatic stress I suffer now is worse than what I actually experienced in battle,” he says, pointing out a gunshot wound to his face.

Now, with a felony assault charge, Pinkela is having a hard time finding work even at a hardware store. “I was good at what I did. I loved my job. Now I can’t even get a job.”

Pinkela’s case is not unique. Other HIV positive service members interviewed say that serving their country while fighting for access to HIV care or preventative treatments is an uphill battle rife with bureaucracy, old science and misnomers within the Department of Defense on how HIV is transmitted. Much of the problem has to do with education, but both LGBTQ and HIV advocates say the issue is framed within the military’s staunch conservatism around sexual activity – particularly when it comes to gay sex.

The military isn’t alone in their policies; state laws also give prosecutors authority to charge those who have HIV with felony assault, battery and in some cases rape for having unprotected sex. As a result, gay men are facing what they say is an ethos of discrimination by the military against those who have HIV, including barring people from entering the services and hampering deployment to combat zones.

“It’s not a death disease anymore.”

Nationally, HIV transmission rates have gone down as access to medication and education have increased. But since tracking HIV within the armed forces, positive tests have “trended upwards since 2011,” according to the Defense Health Agency’s Medical Surveillance Monthly Report published in 2015. The highest prevalence of HIV is among Army and Navy men, according to the report.

In 1986, roughly five years after the HIV and AIDS epidemic began, the military began testing for HIV during enlistment, and barred anyone who tested positive. By the time the AIDS crisis began to lessen in the mid-1990s, the Army and Navy started testing more regularly. Now, service members are tested every two years, or before deployment.

Medical advocates say that the current two-year testing policy is partially to blame for the increase by creating a false sense of security against sexually transmitted diseases. The Centers for Disease Control suggest testing for HIV every three months for people who are most at risk of getting the virus, such as gay men or black men who have sex with men.

“The military, depending on how you look at it, could be seen as high risk for contracting HIV,” says Matt Rose, policy and advocacy manager with the National Minority AIDS Council in Washington D.C. “The military likes to treat every service member the same, but it makes testing for HIV inefficient.”

Former Cpt. Josh Seefried, the founder of the LGBTQ military group OutServe, said the group identified HIV as a problem within the armed forces nearly a decade ago after anonymously polling members.

“People have this mindset that since you’re tested and you’re in the military, it must be OK to have unprotected sex,” he says. “That obviously leads to more infection rates.”

Such was the case for Brian Ledford, a former Marine who tested positive right before his deployment out of San Diego. He told Rolling Stone he never got tested consistently because of the routine tests offered by the Navy. “I was dumb and should’ve known better, but I just thought, you know, I’m already getting tested so it’ll be fine.”

But a larger problem for the military is the number of civilians who try to enlist and test positive. The Defense Health Agency last year said there was a 26 percent increase of HIV positive civilians trying to sign up for the service.

All of those people, per military policy, were denied enlistment.

A Department of Defense spokesperson told Rolling Stone that the military denies HIV positive enlistees because the need to complete training and serve in the forces “without aggravation of existing medical conditions.”

But gay military groups say the policy is simply thinly-veiled discrimination.

“This policy, just like every other policy that was put in place preventing LGBTQ people from serving, is discriminatory and segments out a finite group of people,” says Matt Thorn, the current executive director of OutServe-SLDN. “Gen. Mattis during his confirmation said he wanted the best of the best to serve. If someone wants to serve their country they should be allowed to serve their country.”

The U.S. is one of the few Western nations left that have a ban on HIV positive enlistees. In Israel, where service is compulsory, their ban was lifted in 2015. In a press conference, Col. Moshe Pinkert of the Israeli Defense Forces said that “medical advancement in the past few years has made it possible for [those tested positive] to serve in the army without risking themselves or their surroundings.”

And as more countries begin to change their attitudes toward HIV and embrace a more inclusive military policy, there is hope that the U.S. might follow suit.

“Lifting the ban on transgender service members and Don’t Ask Don’t Tell was because a lot of other countries had lifted those bans, as well,” says Thorn. “In general, we don’t have a lot of good education awareness within the military on being HIV positive. People are looking back and they’re reflecting back on those initial horrors. But the truth of the matter is that it’s not a death disease anymore.”

Stuck in the 1980s

In July 2007, Pinkela was just about to be deployed out of Fort Hood when he was brought into an office; he was then told the news about his HIV status.

After the shock set in, he returned back to the D.C. area where he was required to sign what is known in the military as a “Safe Sex Order.” The order requires service members to follow strict guidelines on how they approach contact with others due to their diagnosis. If violated, soldiers can face prosecution or discharge.

“That piece of paper was a threat,” says Pinkela. “I couldn’t believe it was something that we did. Even to this day I look back on it and can’t believe that someone thought the order was okay.”

The Safe Sex Orders differ slightly between the military branches, but some of the details are troubling to medical professionals who say it appears as though the military is stuck in the 1980s.

For example, guidelines in the Air Force and Army tell soldiers to keep from sharing toothbrushes or razors. But the science and medical communities have known for decades that HIV can’t survive outside of the human body and needs a direct route to the bloodstream – something razors and toothbrushes can’t provide.

The Navy and Marine guidelines also tell service members to prevent pregnancy, as transmission of HIV between the mother and child may occur. But transmission between mother and child has become exceedingly rare.

“It’s your right to procreate,” says Catherine Hanssens, executive director of the HIV Law and Policy Center. “To effectively say to someone that because you’re HIV positive, even if you inform your partner, you shouldn’t conceive a child raises constitutional issues.”

Since 2012, HIV transmission has had a dramatic turnaround – partially due to preventative treatments that make the virus so hard to contract.

When someone is on HIV medication, they can reach an “undetectable” level of virus in their blood. At that point, transmission of HIV without a condom is nearly impossible, according to studies conducted in 2014 and released last year.

Rolling Stone reached out to the Department of Defense to specify why, given the medical advancement and low transmission rate, Safe Sex Orders were still being issued in their current format. The department defended the orders, saying “It is true that the risk is negligible if… the HIV-infected partner has an undetectable HIV viral load. However, it cannot be said that the risk is truly zero percent.”

If a service member breaks any of these rules, the military can charge them under the Uniform Code of Military Justice with assault, battery, rape or conduct unbecoming of an officer or gentleman.

Though department officials told Rolling Stone that “the Army does not use the [policy] to support adverse action punishable under UCMJ,” Hanssens’ organization currently represents service members who are facing charges as a result of not following their Safe Sex Order.

But military advocates – and even their staunch opponents – have said the U.S. military is just falling in line with other states throughout the country that criminalize HIV transmission and exposure. There are currently 32 states that have laws on the books related to HIV.

“Safe Sex Orders are unfortunately consistent with some laws enacted within certain states,” says Jonathon Rendina, an Assistant Professor at Hunter College at The City University of New York’s Center for HIV and Education Studies and Training. “What the military is doing is no different that what many civilian lawmakers are doing.”

In 2011, California Rep. Barbara Lee introduced a bill that would end HIV criminalization nationwide, though it failed to pass. In 2013, she helped push a line in the National Defense Authorization Act that forced the Department of Defense to review its HIV policies; though, only the Navy made changes to their Safe Sex Order.

“Too often, our brave service members are dismissed – or even prosecuted – because of their status,” Lee tells Rolling Stone in an email. “These shameful policies are based in fear and discrimination, not science or public health.”

Such was the case for Pinkela, who feels that the military has been using HIV as a reason to prosecute and kick out gay men since the legislative repeal of Don’t Ask Don’t Tell in 2010.

“I could not have sex. And even if I had sex and I told somebody, someone in the military could still prosecute me. They have this little piece of paper that lets some bigot and someone who doesn’t understand us, slam us and put us in jail,” he says.

And he’s not alone. Seefried, the retired Air Force captain, says he advises his gay friends – he calls them “brothers” – not to join the military.

“Right after Don’t Ask Don’t Tell was repealed, I came out and I said that gays should join to help change the culture,” Seefried says. “Now, I tell them not to not sign up… I just think that policies are very, very bad and unsafe for gays in the military right now.”

Quality care, for some

Travis Hernandez, a former sergeant in the Army, has been on the drug Truvada for just under two years now. He started using the the once-a-day blue pill while stationed at Ft. Bragg after he learned from a hook up that the drug could prevent HIV transmission by nearly 100 percent.

“A guy I was in the Army with and having sex with told me about it, and I was sexually active so it made sense for me to try it,” Hernandez says, adding how his experience getting the drug through the Army was very positive. “The doctors were really open talking about safe sex and everyone was very nice. I didn’t have any issues getting the drug.”

Hernandez finished his Army service last year and continues to receive Truvada through his veteran health benefits. But his story is not similar to everyone else’s.

The military provides access to Truvada through it’s healthcare provider TriCare, but only for certain individuals. Each military branch makes their own rules for who can get access.

Emails obtained by Rolling Stone between the National Minority AIDS Council and military health officials confirm that there are different protocols for prescribing Truvada between the service branches and its members without any specific reason.

“The military likes to set their own rules, even if it doesn’t always make sense,” says Rose, with the council. “The Army thinks they know what’s best for the Army, and Marines think they know what’s best for the Marines. But they all have different medical requirements that shouldn’t have any dissimilarities.”

In a statement, Military Health officials within the Department of Defense say they are conducting studies on the effectiveness of Truvada in certain situations, such as while on flight status or sea duty, and are also looking into barriers service members faced with access to care across the military branches. Among those barriers, Military Health noted that not every military hospital has infectious disease specialists who would prescribe the drug.

Truvada does not require a prescription from an infectious disease doctor, though. And the different policies, Seefried says, shows the lack of scientific competence within the Department of Defense and the policies they create.

“Navy Pilots, for example, can take Truvada while on the flight line, but Air Force pilots cannot while they are on the flight line,” says Seefried. “These military branches have different chains of command, so they have different policies that all agree on nothing. It’s just disjointed, and not grounded in science.”

Once a prison, now a home

The charges brought against Pinkela are confusing – even to lawyers who have reviewed his case. Hanssens, with the HIV Law and Policy Center, was one of them.

“What happened to him makes no sense,” she said.

Typically, when a prosecutor files charges, certain requirements have to be met. For assault and battery, according to the UCMJ, one of the primary actions has to be an unwanted physical and violent encounter or an action that is likely to cause death. There are no statutes that label the virus as a determinant for the charge.

Despite there not being an authorization on the books, scores of HIV positive service members like Pinkela have been brought before a court martial with felony assault and battery charges.

Pinkela’s case had gone through six prosecutors who thought the case was too weak before one finally picked it up, according to Pinkela.

And Pinkela’s court martial testimonies are even more bizarre: the soldier never said Pinkela and he had sex, nor did he ever say that Pinkela was the one who transmitted the virus to him. Instead, the evidence came down to an anal douche that may have been used and could’ve exposed the young soldier to HIV.

Not possible, says Rendina, the investigator from the City University of New York.

“Like most viruses, HIV is destroyed almost immediately upon contact with the open air,” he said. “The routes of transmission [listed in Pinkela’s case] have an extremely low probability of spreading infection due to the multiple defenses along the route from one body to the next – this is made even more true if the HIV-positive individual is also undetectable.”

When asked about the case, the Army only confirmed Pinkela’s charges but wouldn’t comment on the nature of the case or how HIV is prosecuted, generally, within the armed forces.

Pinkela has run out of appeals and is forced to now move forward with what little means he has. But in true spirit of service, he has found a new way to give back to the small town that he’s been forced to live in. In May, Pinkela plans to announce his plans to run for office in Otisville.

“I still believe in this country. And I still believe in the service, no matter that it’s the same system that allowed for this to happen to me,” he said.

In an effort to move past the experience, Pinkela and a friend went to last year’s Burning Man – the art and music festival held in Death Valley, California. There, when the fires began burning on the last day, he wrapped up his Army uniform, tied it off and threw it in a fire. He said it was one of the most cathartic moments he’s felt since being back in the Army.

Published in Rolling Stones on May 20, 2017

US: American Pyschological Association's entire March newsletter explores why HIV criminalisation "can no longer be ignored."

APA’s commitment to decriminalizing HIV

By Maggie Chartier, PsyD, and Tiffany Chenneville, PhD

In 2016, the APA joined the ranks of medical and professional organizations opposing HIV criminalization laws (Positive Justice Project Consensus Statement on the Criminalization of HIV in the U.S., n.d.). Since 1986, these laws have criminalized nondisclosure of HIV and engagement in “risk” behaviors (sexual activity, needle sharing, and in some instances spitting and biting) for those who are aware of their HIV status (Lehman, Carr, Nichol, Ruisanchez, Knight, Langford, et al., 2014). Between 1986-2011, 67 HIV-specific criminal laws were enacted in 32 states and two U.S. territories (Lehman, 2014), many or most of which do not consider the level of risk and/or intentionality of the act.

Since the beginning of the AIDS epidemic, hundreds of people living with HIV have been arrested for behaviors posing little, if any, risk of HIV transmission (CDC, 2015). It is estimated that 20-25 percent of prosecuted cases related to HIV exposure/transmission have involved spitting, biting or external exposure to bodily fluids (e.g., throwing bodily fluids) which pose negligible transmission risk (CDC, 2015; Patel, Borkowf, Brooks, Lasry, Lanksy & Mermin, 2014; Pretty, Anderson & Sweet, 2009).

Many HIV-specific criminalization laws were passed before research showed that:

- Consistent condom use significantly reduced the spread of HIV (Pinkerton & Abramson, 1997).

- Adherence to antiretroviral therapy results in undetectable viral loads which dramatically reduce HIV transmission (Dieffenbach & Fauci, 2009 [PDF, 119KB]).

- Increased efficacy of post-exposure prophylaxis and pre-exposure prophylaxis and are efficacious in preventng HIV (Celum & Baeten, 2012; van der Straten, Van Damme, Hbere & Bangsberg, 2012; Young, Arens, Kennedy, Laurie & Rutherford, 2007).

People diagnosed with HIV in states with HIV-specific criminal laws must disclose their HIV serostatus to sex partners and injection needle sharing partners and refrain from various sexual behaviors, regardless of actions taken to minimize HIV risk transmission (e.g., consistent condom use, using clean needles, consistent adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy [ART]). In the rare instances in which intentional transmission of HIV is determined, states may use general criminal laws or communicable disease laws to prosecute persons accused of intentionally trying to transmit HIV instead of HIV-specific criminal laws.

Not only do most HIV criminalization laws ignore the level of risk or intentionality of the action, they also do not reflect the current, and considerable, evidence base on HIV transmission (CDC, 2015), and in many instances, they counteract public health efforts to decrease HIV transmission by increasing stigma and discrimination (Valdiserri, 2002). As a result, in 2014, the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice issued a “Best Practices Guide to Reform HIV-Specific Criminal Laws to Align with Scientifically-Supported Factors (PDF, 117KB).”

This newsletter will present a human face to HIV criminalization laws and discuss the public health implications and the role that psychological research and practice can play in helping to address the individual and social impact of these laws. By emphasizing this issue, APA strongly encourage states with HIV criminalization laws to repeal such laws and provide psychologists practicing in relevant states with guidance on the impact that HIV-specific laws may have on their clients and the general public’s health.

For more information on APA’s resolution, visit the Background Information on the Resolution Opposing HIV Criminalization webpage.

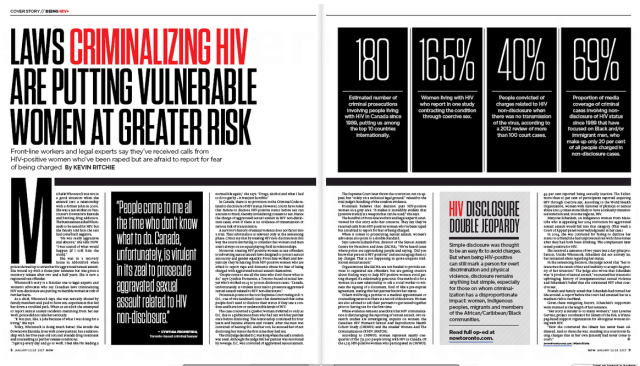

Canada: Toronto’s ‘Now’ weekly newspaper prominently features HIV criminalisation impact, advocacy and advocates

This week, Toronto’s weekly newspaper, ‘Now’, features four articles on HIV criminalisation and its impact in Canada.

The lead article, ‘HIV is not a crime’ is written from the point of view of an HIV-negative person who discovers a sexual partner had not disclosed to him. It concludes:

After my experience with non-disclosure, I felt some resentment. But while researching this article, I reached out to the person who didn’t disclose to me. We talked about the assumptions we’d both made about each other. It felt good to talk and air our grievances.

I realized I’d learned something I’d never heard from doctors during any of my dozens of trips to the STI clinic, something I’d never heard from my family, my school, in the media or from the government – that you don’t need to be afraid of people living with HIV.

A second article, Laws criminalizing HIV are putting vulnerable women at greater risk, highlights the impact HIV criminalisation is having on women in Canada, notably that it is preventing sexual assault survivors living with HIV from coming forward due to a fear they will be prosecuted for HIV non-disclosure (which, ironically, is treated as a more serious sexual assault than rape).

A second article, Laws criminalizing HIV are putting vulnerable women at greater risk, highlights the impact HIV criminalisation is having on women in Canada, notably that it is preventing sexual assault survivors living with HIV from coming forward due to a fear they will be prosecuted for HIV non-disclosure (which, ironically, is treated as a more serious sexual assault than rape).

Moreover, treating HIV-positive women as sex offenders is subverting sexual assault laws designed to protect sexual autonomy and gender equality. Front-line workers and lawyers say they’re hearing from HIV-positive women who are afraid to report rape and domestic abuse for fear of being charged with aggravated sexual assault themselves.

“People come to me all the time who don’t know what to do,” says Cynthia Fromstein, a Toronto-based criminal lawyer who’s worked on 25 to 30 non-disclosure cases. “Canada, unfortunately, is virulent in its zeal to prosecute aggravated sexual assault related to HIV non-disclosure.”

It also features a strong editorial, ‘HIV disclosure double jeopardy’ by the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network’s Cecile Kazatchkine and HALCO’s Executive Director, Ryan Peck, which notes:

It also features a strong editorial, ‘HIV disclosure double jeopardy’ by the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network’s Cecile Kazatchkine and HALCO’s Executive Director, Ryan Peck, which notes:

In a statement that mostly flew under the radar, Minister of Justice Jody Wilson-Raybould declared, on World AIDS Day (December 1), her government’s intention “to examine the criminal justice system’s response to non-disclosure of HIV status,” recognizing that “the over-criminalization of HIV non-disclosure discourages many individuals from being tested and seeking treatment, and further stigmatizes those living with HIV or AIDS.”

Wilson-Raybould also stated that “the [Canadian] criminal justice system must adapt to better reflect the current scientific evidence on the realities of this disease.”

This long-overdue statement was the first from the government of Canada on this issue since 1998, the year the Supreme Court of Canada released its decision on R v. Cuerrier, the first case to reach the high court on the subject.

Finally, the magazine features a number of promiment HIV activists from Canada, including Alex McClelland, who is studying the impact of HIV criminalisation on people accused and/or convicted in Canada.

Finally, the magazine features a number of promiment HIV activists from Canada, including Alex McClelland, who is studying the impact of HIV criminalisation on people accused and/or convicted in Canada.

HIV Criminalization: Masking Fear and Discrimination (Sero, US, 2016)

A short documentary for the Sero Project produced by Mark S King, written by Christopher King, and edited by Andrew Seger.

Canada: ‘HIV is not a crime’ documentary premieres in Montreal at Concordia University’s ‘The Movement to End HIV Criminalization’ event

Last week, Concordia Unversity in Montreal, Canada, held the world premiere public screening of HJN’s ‘HIV is not a crime training academy’ documentary, followed by three powerful and richly evocative presentations by activist and PhD candidate, Alex McClelland; HJN’s Research Fellow in HIV, Gender, and Justice, Laurel Sprague; and activist and Hofstra University Professor, Andrew Spieldenner.

The meeting, introduced by Liz Lacharpagne of COCQ-SIDA and by Martin French of Concordia University – who put the lecture series together – was extremely well-attended, and resulted in a well-written and researched article by student jounrnalist, Ocean DeRouchie, alongside a strong editorial from Concordia’s newspaper, The Link.

(The full text of both article and editorial are below.)

Presentations included:

- Edwin Bernard, Global Co-ordinator, HIV Justice Network: ‘The Global Picture: Surveying the State of HIV Criminalisation’

- Alex McClelland, Concordia University: ‘Criminal Charges for HIV Non-disclosure, Transmission and/or Exposure: Impacts on the Lives of People Living with HIV’

- Laurel Sprague, Research Fellow in HIV, Gender, and Justice, HIV Justice Network: ‘Your Sentence is Not My Freedom: Feminism, HIV Criminalization and Systems of Stigma’

- Andrew Spieldenner, Hofstra University: ‘The Cost of Acceptable Losses: Exploring Intersectionality, Meaningful Involvement of People with HIV, and HIV Criminalization’

Articles based on a number of these important presentations will be published on the HJN website in coming

weeks.

The Movement to End HIV Criminalization

Decrying Criminalization

Concordia Lecture Series Prompts Discussion on HIV Non-disclosure

The sentiment surrounding HIV/AIDS is often one of discomfort. But the reluctance to speak openly about such a significant and impactful disease is hurting the people closest to it.

Under current Canadian legislation, HIV non-disclosure is criminalized. It exercises some of the most punitive aspects of our criminal justice system, explained Alexander McClelland, a writer and researcher currently working on a PhD at Concordia.

McClelland was one of four panelists speaking under Concordia’s Community Lecture Series on HIV/AIDS on Thursday, Sept. 15 in the Hall building. The collective puts on multiple panel-based events in order to address the attitudes, laws, and intersections of political and socioeconomic stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS.

Talking About HIV, Legally

There are three distinct charges that guide prosecutors in HIV cases—transmission (giving the disease to someone without having disclosed your status), exposure (e.g. spitting or biting) and non-disclosure (not informing a sexual partner about your HIV/AIDS status).

Aggravated sexual assault and attempted murder are some of the charges that defendants often face, explained Edwin Bernard, Global Coordinator for the HIV Justice Network, during the discussion.

While there are clearly defined situations in which you are legally obligated to tell a sex partner about your HIV status, there are no HIV-specific laws. This results in the application of general law in cases that are anything but general.

In 2012, the Supreme Court of Canada established that “people living with HIV must disclose their status before having sex that poses a ‘realistic possibility of HIV transmission.’”

Aidslaw.ca presents a clear map of situations in which you’d have to tell a sex partner about your status because, in fact, it is not in all scenarios that you’d be legally required to have the discussion.

A lot of it depends on your viral load—the amount of measurable virus in your bloodstream, usually taken in milliliters. A “low” to undetectable viral load is the goal, and is achieved with anti-viral medication.

Treatment serves to render HIV-positive individuals non-infectious, and therefore lowering the risk of transmission. A “high” viral load indicates increased amounts of HIV in the blood.

If protection is used and with a low viral load, one might not have to disclose their status at all.

That said, there is a legal obligation to disclose one’s HIV-positive status before any penetrative sex sans-condom, regardless of viral load. You’d also have to bring it up before having any sex with protection if you have a viral load higher than “low.”

But not all sex is spelled out so clearly.

Oral sex, for instance, is a grey area. Aidslaw.ca says, “oral sex is usually considered very low risk for HIV transmission.” They write that “despite some developments at lower level courts,” they cannot say for sure what does not require disclosure.

There are “no risk” activities. Smooching and touching one another are intimate activities that, as health professionals say, pose such a small risk of transmission that there “should be no legal duty to disclose an HIV-positive status.”

Moving Up, and Out of Hand

Court proceedings are based on how the jury and judge want to apply general laws to specific instances. There are a lot of factors that can influence the outcome.

The case-to-case outlook leads to the criminal justice system dealing with non-disclosure in such a disproportionate way, said McClelland.

The situation begs the question: “Why is society responding in such a punitive way?” asked McClelland.

This isn’t to say that not disclosing one’s HIV status “doesn’t require some potential form of intervention,” he explained, adding that intervention could incorporate counseling, mental-health support, encouragement around building self-esteem and learning how to deal and live with the virus in the world. “But in engaging with the very blunt instrument that is the criminal law is the wrong approach.”

He continued to explain that the reality of the criminalization of HIV ultimately doesn’t do anything to prevent HIV transmission.

“It’s just ruining people’s lives,” said McClelland, who has been interviewing Canadians who have been affected by criminal charges due to HIV-related situations. “It’s a very complex social situation that requires a nuanced approach to support people.”

“It’s just ruining people’s lives. It’s a very complex social situation that requires a nuanced approach to support people.” – Alexander McClelland, Concordia PhD student

Counting the Cases

The Community AIDS Treatment Information Exchange, a Canadian resource for information on HIV/AIDS, states that about 75,500 Canadians were living with the virus by the end of the 2014, according to the yearly national HIV estimates.

That number has gone up since. On Monday, Sept. 19, Saskatoon doctors called for a public health state of emergency due to overwhelmingly increasing cases of new infections and transmission, according to CBC.

In Quebec, there have been cases surrounding transmission and exposure. In 2013, Jacqueline Jacko, an HIV-positive woman, was sentenced to ten months in prison for spitting on a police officer—despite findings that confirm that the disease cannot be transmitted through saliva.

In this situation, Jacko had called for police assistance in removing an unwelcome person from her home. Aggression transpired between her and the officers, resulting in her arrest and eventually her spitting on them, according to Le Devoir.

“[This case] is so clearly based on AIDS-phobia, AIDS stigma and fear,” added McClelland, “and an example of how the police treat these situations and use HIV as a way to criminalize people.”

Police intervention is crucial in the fight against HIV criminalization. McClelland urged people to consider the consequences of involving the justice system in these kinds of situations.

“It’s important to understand that the current scientific reality for HIV is that it’s a chronic, manageable condition. When people take [antivirals] they are rendered non-infectious,” he said. “They should then understand that the fear is grounded in a kind of stigma and historical understanding of HIV that is no longer correct today.”

The first instinct, or notion of calling the police in an instance where one feels they may have been exposed to the virus in some way is “mostly grounded in fear and panic,” he said.

“[Police] respond in a really disproportionate, violent way towards people—so I would consider questioning, or at least thinking twice before calling the police,” McClelland explained.

On the other hand, he suggested approaching the situation in more conventional, educational and progressive methods.

“I think it could be talked through in different ways—by going to a counselor, talking to a close friend, engaging with a community organization, learning about HIV and what it means to have HIV, and understanding that the risk of HIV transmission are very low because of people being on [antivirals].”

As for the current state of Canadian legislation, there are a lot of complexities that hinder heavy-hitting changes to the laws.

Due to the Supreme Court’s rulings in 2012, they are unlikely to review the decision for another decade. For now, the main course of action is “on the ground,” said McClelland. From mitigating people from requesting police involvement in order to “slow down the cases,” to raising awareness through events such as Concordia’s Community Lecture Series, and engaging with the people to resolve issues in community-based ways and collective of care.

Then, McClelland said, “trying to do high-level political advocacy to get leaders to think about how they can change the current situation” would be the next step.

Editorial: Community-Based Research is the Key to HIV Destigmatization and Decriminalization

Receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis is already a life sentence. The state of Canada’s legal system threatens to give those living with the virus another one.

An HIV diagnosis is accompanied by its own set of complexities that are not encompassed in Canada’s criminal law. By pushing HIV non-disclosure cases into the same box as more easily defined assault cases, we are generalizing an issue that frankly cannot be simplified.

This does not reflect the reality that one faces when living with HIV. Criminalizing the virus further stigmatizes what should and could be everyday activities.

This puts the estimated 75,000 Canadians living with HIV at risk of being further isolated. This takes us backwards, considering the scientific progress that has been made to make living with the virus manageable. Under the proper antiviral medication, one’s risk of transmitting the disease is incredibly low. This stigma is rooted in an antiquated understanding of what HIV is and the associated risks—much of that fear having emerged primarily as a result of homophobia.

Further, with over 185 cases having been brought to court, Canada is leading in terms of criminalizing HIV non-disclosure. This pushes marginalized communities farther away. According to estimates from 2014, indigenous populations have a 2.7 higher incidence rate than the non-indigenous Canadian average. Gay men have an incidence rate that is 131 times higher than the rest of the male population in Canada.

As of Sept. 19, doctors in Saskatchewan are calling on the provincial government to declare a public health state of emergency, with a spike in HIV/AIDS cases around the province.

In 2010, it’s reported that indigenous people accounted for 73 per cent of all new cases in the province. Outreach and treatment for these communities are at the forefront of Saskatchewan’s doctor’s recommendations for the government.

With such a highly treatable virus, however, the problem should never have gone this far. It is an excerpt from a much bigger issue.

As we can see from the available statistics, HIV—both the virus and its criminalization—is a mirror for broader inequalities that exist within society. HIV related issues disproportionately affect racialized people, gender non-conforming people, and other marginalized groups.

Discussions around HIV also must include discussions around drug use. The heavy criminalization of injection drugs has created a context where users are driven deep underground, thus putting them at an incredibly high risk for contracting the virus. Treating drug use as a health rather than a criminal issue is an integral part of any effective HIV prevention strategy. Safe injection sites, such as Vancouver’s InSite, have made staggering differences in their communities and prove to be a positive way of combating the spread of HIV.

This is just one of the many ways that we can control the spread of HIV without judicial intervention, without turning the HIV-positive population into criminals.

Using community-based research enables us to not only understand the needs of the affected population—particularly when it comes to understanding the almost inherent intersectionality associated with the spread of HIV—but also allows us to better target our resources towards those who need it most.

Often times, that stretches to include those closest to HIV-positive individuals. Spreading awareness, and developing resources and a support network for them is just as important in fighting the stigmatization of the virus.

The Link stands for the immediate decriminalization of HIV non-disclosure, and the move towards restorative justice systems in non-disclosure cases. As always, those directly affected by an issue are the ones with who are best positioned to create a solution—something that the restorative justice framework embraces.

The disclosure of one’s HIV status is important. Jailing those who don’t disclose it, however, won’t make the virus go away. It simply isolates the problem, places it out of site and out of mind.

Criminalizing HIV patients is less about justice than it is about appeasing the baseless fears of the general population. It’s time for a more effective solution.

Video and written reports for

Beyond Blame: Challenging HIV Criminalisation at AIDS 2016

now available

On 17 July 2016, approximately 150 advocates, activists, researchers, and community leaders met in Durban, South Africa, for Beyond Blame: Challenging HIV Criminalisation – a full-day pre-conference meeting preceding the 21st International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2016) to discuss progress on the global effort to combat the unjust use of the criminal law against people living with HIV. Attendees at the convening hailed from at least 36 countries on six continents (Africa, Asia, Europe, North America, Oceania, and South America).

Beyond Blame was convened by HIV Justice Worldwide, an initiative made up of global, regional, and national civil society organisations – most of them led by people living with HIV – who are working together to build a worldwide movement to end HIV criminalisation.

The meeting was opened by the Honourable Dr Patrick Herminie, Speaker of Parliament of the Seychelles, and closed by Justice Edwin Cameron, both of whom gave powerful, inspiring speeches. In between the two addresses, moderated panels and more intimate, focused breakout sessions catalysed passionate and illuminating conversations amongst dedicated, knowledgeable advocates.

WATCH THE VIDEO OF THE MEETING BELOW

A tremendous energising force at the meeting was the presence, voices, and stories of individuals who have experienced HIV criminalisation first-hand. “[They are the] folks who are at the frontlines and are really the heart of this movement,” said Naina Khanna, Executive Director of PWN-USA, from her position as moderator of the panel of HIV criminalisation survivors; “and who I think our work should be most accountable to, and who we should be led by.”

Three survivors – Kerry Thomas and Lieutenant Colonel Ken Pinkela, from the United States; and Rosemary Namubiru, of Uganda – recounted their harrowing experiences during the morning session.

Thomas joined the gathering via phone, giving his remarks from behind the walls of the Idaho prison where he is serving two consecutive 15-year sentences for having consensual sex, with condoms and an undetectable viral load, with a female partner.

Namubiru, a nurse for more than 30 years, was arrested, jailed, called a monster and a killer in an egregious media circus in her country, following unfounded allegations that she exposed a young patient to HIV as the result of a needlestick injury.

Lt. Col. Pinkela’s decades of service in the United States Army have effectively been erased after his prosecution in a case in which there was “no means likely whatsoever to expose a person to any disease, [and definitely not] HIV.”

At the end of the brief question-and-answer period following the often-times emotional panel, Lilian Mworeko of ICW East Africa, in Uganda, took to the microphone with distress in her voice that echoed what most people in the room were likely feeling.

“We are being so polite. I wish we could carry what we are saying here [into] the plenary session of the main conference.”

With that, a call was put to the floor that would reverberate throughout the day, and carry through the week of advocacy and action in Durban.

This excerpt is from the opening of our newly published report, Challenging HIV Criminalisation at the 21st International AIDS Conference, Durban, South Africa, July 2016, written by the meeting’s lead rapporteur, Olivia G Ford, and published by the HIV Justice Worldwide partners.

The report presents an overview of key highlights and takeaways from the convening grouped by the following recurring themes:

- Key Strategies

- Advocacy Tools

- Partnerships and Collaborations

- Adopting an Intersectional Approach

- Avoiding Pitfalls and Unintended Consequences

Supplemental Materials include transcripts of the opening and closing addresses; summaries of relevant sessions at the main conference, AIDS 2016; complete data from the post-meeting evaluation survey; and the full day’s agenda.

Beyond Blame: Challenging HIV Criminalisation at AIDS 2016 by HIV Justice Network on Scribd