A year ago, in April 2015, the French National AIDS and Viral Hepatitis Council (Conseil national du sida et des hépatites virales, known simply as ‘CNS’) following extensive research into the law, nature of complaints and prosecutions, and their impact, issued a report, opinion and recommendations.

An English language version of the report, opinion and subsequent recommendations is still being prepared.

Earlier this year, Professor Patrick Yeni (pictured), chair of the CNS, was interviewed by Jean-François Laforgerie on the French language HIV website, seronet.info. His interview is eye-opening and powerful.

It highlights that although they had only found 23 convictions up to the end of 2014, surveys of people living with HIV suggest that up to 2000 complaints may have been made since the start of the epidemic.

The survey shows that slightly more than one person living with HIV in ten claims to have been tempted to complain against the person that they believed to be the source of infection. According to the same source, 1.4% of people living with HIV surveyed reported having actually complained. Based on these figures, we estimate an order of magnitude from 1 500 to 2 000 complaints that could be filed in total since the beginning of the epidemic.

He also notes that the law currently only recognises condom use as a way to show lack of a guilty mind, and he and his colleagues are concerned that up-to-date science is not reflected in the law. He also highlights that in France disclosure of known HIV-positive status – and subsequent consent to ‘risky’ sex – is not actually a defence, although in practice only cases where no disclosure took place and where no condoms were used have reached the court.

It seems unthinkable that what is obvious in terms of public health today on the promotion of biomedical preventions is lagging behind legally.

Given the importance of this body of work, we have decided to publish the interview and a summary of the main CNS recommendations beneath it, despite no official English translation.

It is interesting that the people who complain and go to trial are not part of the so-called risk groups where prevalence is high. For example, there is virtually no migrants among the complainants. Moreover, today there is a much greater legalisation of intimacy, including sexual facts than existed in the past. Perhaps this plays on the fact that people complain more now than twenty years ago.

Below is the English translation of the seronet.info interview, further improved from Google translate’s version by Sylvie Beaumont. Version anglaise via Google translate. Le texte français est après la traduction.

Q: In 2006, the National AIDS and viral hepatitis Council (CNS) published their review of the criminalisation of HIV transmission. What led you to work again on this issue and publish, in 2015, a second opinion?

Patrick Yeni [PY]: The media coverage of some trials in France and, secondly, the situation internationally. In other countries, there was an active debate on the criminalisation of HIV transmission, while in France this reflection seemed stalled. These are the two reasons that led us to revisit this issue, trying to understand and think about how things had changed since our first review.

Q: In your 2015 recommendations, you noted that the attention paid to legal, ethical and health issues relating to criminalisation of HIV transmission was low, both on the part of public authorities and civil society actors. How do you explain that?

PY: We have no clear answer to that. This is also why we wanted to restart the debate. If one takes the point of view of government and we take stock of court cases – 23 convictions for HIV transmission since the beginning of the epidemic throughout France – one can imagine that for the state this is not a national major problem at the criminal level, at least quantitatively. I guess the debate on criminal justice focuses primarily on other issues. For HIV organisations, it is probably more complicated because legal proceedings – as we attempt to analyse them in the recommendations – somewhat undermined the historical foundations on which the fight against HIV is based. By that I mean solidarity between people living with HIV and the refusal to distinguish between “patients as victims” allegedly infected and others who simply became infected. I imagine that this problem could have induced some inertia in advancing the debate. One recommendation from the CNS is to urge organisations to resume this discussion today, because it is a lever to act on issues of stigma, discrimination … and HIV prevention in general.

Q: What is prosecuted today? And what is a crime under the law?

PY: Primarily the fact that a person who knows s/he is HIV-positive, transmits HIV to a partner while s/he has not taken preventive measures to prevent this, i.e used a condom. In almost all trials in France, this is what has been prosecuted. We have had discussions on other issues as lawyers who supported us explained that the scope of what could be prosecuted or what could be an offence is probably wider than what is actually applied today.

Q: What are you referring to?

PY: One must think on several levels. The first criterion is that they are people who know they are HIV-positive. But it’s more complicated. Thus, from a legal point of view, we cannot know that a person, while not knowing officially that they are HIV-positive would consider themselves to be negative while they are engaged in repeated risky sexual behaviour. Justice may consider that even if they did not know their status officially, their sexual behaviour should have pushed them to consider themselves as potentially HIV-positive, and therefore to do a test and take preventive measures. In this case, the absence of screening does not guarantee the absence of criminal risk. The second criterion is that there must be proof that the person has transmitted HIV. Our analysis of judgments shows that exposing someone to HIV transmission, even without actual transmission can also be penalised. There have been convictions in France for exposure to the risk of transmission. This has occurred in the case of additional convictions to convictions for actual transmission, but it exists.

Q: So you think we could one day have a conviction on the sole ground of the risk of exposure to HIV transmission?

PY: Yes. The legal elements are there. That is, according to our analysis, another possibility of expanding the criminal field. The third criterion is that the ‘victim’ is not aware of the HIV status of their partner. In criminal law, whether or not the victim is informed does not exempt the defendant from liability. One cannot argue that the partner was informed and has agreed not to protect themselves and therefore would not be responsible. The information is not enough.

Fourth criterion. In all cases today, sexual prevention is understood as the use of condoms. It is the condom which is retained as the manifestation of concerns relating to the risk of transmission. We do not know what will happen when there will be proceedings for transmission or exposure by people who do not use condoms, but are treated effectively. Some lawyers have told us that if there was transmission despite condom use, it would be a case of force majeure which is exculpatory of responsibility. We can not guarantee the same thing about treatment. In other words, even with a good track treatment, a viral load of less than 20 copies, one cannot guarantee that there is not occasionally a little HIV in semen … and therefore transmission is possible even if treatment is adhered to, and viral load is undetectable … other lawyers tell us that we are, in this case, in a random situation, which does not exempt the person with HIV from responsibility. We must think about this. It seems unthinkable that what is obvious in terms of public health today on the promotion of biomedical preventions is lagging behind legally. This is a warning that we mention in the recommendation. But unfortunately we fear that this debate will only take place when a case of transmission from someone on effective treatment will come to court.

Q: How do you explain that the role of treatment as prevention is recognised in Switzerland with all the legal consequences that this entails, and yet the same argument does not hold legally with us?

PY: We wanted to alert on this point precisely so the conclusions of judges, when they have to decide, are identical to the public health conclusions we know today. We must not get to this contradiction where a person who is effectively treated is found guilty because s/he would not use a condom. With these examples, we can see the narrow scope of what is actually prosecuted and that it is imperative to have a debate on the possible expansion of what is a crime.

Q: The argument is often made that further criminalisation would deter people from testing?

PY: The review analysed the consequences of the criminalisation of HIV transmission on testing. All the studies to which we had access, mainly foreign, do not indicate that criminal risk linked to knowing one’s status would lead to decreased use of testing.

Q: You note the paradox that legal proceedings have developed in a context of “normalisation” of the disease. In other words, cases flourished in the 2000s, after the most acute phase of the epidemic. How do you explain it?

PY: We had discussions about it. Some of us were reluctant to say that there was an increase in the number of cases. One thing is certain, we are on a low figure: 23 convictions. Especially if we compare the data of the ANRS-Vespa 2 survey. The survey shows that slightly more than one person living with HIV in ten claims to have been tempted to complain against the person that they believed to be the source of infection. According to the same source, 1.4% of people living with HIV surveyed reported having actually complained. Based on these figures, we estimate an order of magnitude from 1,500 to 2,000 complaints that could be filed in total since the beginning of the epidemic. We do not know why some complaints were accepted and others not, why some were eventually classified and others have prospered. We have, unfortunately, no way to evaluate it. We just know that few cases reach a conviction.

To respond more specifically, one must take into account the fact that there is a significant delay, sometimes ten years from the time a complaint is filed to the time when an appeal judgment is pronounced. It might be possible to say that today there is an increase in the number of procedures, but it is not certain. We must be careful about this point. If this is true, how can we explain it? One hypothesis is that in the early days of the epidemic, when many people died of AIDS, a complaint against a person who was likely to die did not make much sense. Today the situation is different. For people, this may appear more “logical” to do so. We advance this hypothesis, but we don’t have the figures to confirm it. One can also look at who is complaining. It is interesting that the people who complain and go to trial are not part of the so-called risk groups where prevalence is high. For example, there is virtually no migrants among the complainants. Moreover, today there is a much greater legalisation of intimacy, including sexual facts than existed in the past. Perhaps this plays on the fact that people complain more now than twenty years ago.

Q: What goals did you set by publishing this new advice?

PY: Firstly: to inform people living with HIV about the conditions under which their criminal responsibility may be engaged. Our thinking has focused on being able to contribute to a fair justice. How? By raising awareness of the investigators in this matter through the National Schools of Police and Gendarmerie. By working with judges and lawyers. It is not possible for judges to have the technical knowledge about different diseases, we admit. Similarly, we can not consider today that under the pretext that people no longer die of AIDS, HIV is commonplace. This is not possible even today because there is a context of social representations that make it a special disease. However, the situation is not the same today, in particular medical progress has taken place. It is very important that judges and lawyers are aware of this. We propose that the National School of Magistrates opens this debate in its initial training as well as in continuing education. We asked the school director to include a discussion on HIV in its knowledge training. A problem that does not concern judges, is that of upgrading one’s knowledge to contribute to a fair trial. One of our wishes is also to allow a reflection on the position of criminal justice. Prison sentences predominate in cases of HIV transmission and issues of rehabilitation and prevention of relapses are not taken into account, even though the court must ensure both aspects in its approach.

Q: Specifically what do you recommend?

PY: For the Department of Justice to develop a form of observatory monitoring of judgments, to document the characteristics of procedures. The tool does not exist and we had to carry out considerable work to realise our new advice and to find all cases that resulted in convictions. We must create an interdepartmental committee to work on the development and provision of information tools tailored to professional (police, lawyers, judges) and other persons concerned, so that the procedures take account of available scientific and medical data, and for doctors to be better informed about the criminal risk of HIV transmission. It’s lobbying work which we pursue, including with HIV organisations. They must reclaim this question on which they were at a standby. We must recognise that the right to resort to justice is a right for all citizens, that our struggle is not against criminal law, but rather to ensure a fair process and prevent risks of criminalisation.

Summary of the CNS’s 2015 recommendations on HIV criminalisation

| No. |

Objectives |

Recommendations |

Competent authorities

and/or recommendation targets |

| 1 |

Contribute to better information of judges |

Promote initial and continuing education of magistrates and future magistrates on HIV related issues |

French National School for the Judiciary (école nationale de la magistrature) |

| 2 |

Bolster the quality of police investigations |

Promote training actions of police officers and future officers on HIV related issues |

Ministry of the Interior |

| 3 |

Prevent reoffending, enable the integration and reintegration of convicted people and improve their support |

Apply alternatives to custodial sentences |

Ministry of Justice |

| 4 |

Promote the prevention of the prosecution risk |

Contribute to a better understanding of legal issues by the people and communities concerned |

HIV/AIDS associations |

| Support actions aiming to provide information on the legal rights and responsibilities of people living with HIV. |

Ministry of HealthFrench National Institute for Health Prevention and Education (INPES) |

| Promote actions to fight PLHIV stigmatisation and discrimination and prevention actions towards the general population |

Ministry of Health, Regional Health Agencies (ARS), French National Institute for Health Prevention and Education (INPES)Other competent ministriesHIV/AIDS associations |

| 5 |

Provide access to up-to-date and high-quality legal and scientific information |

Implement a reporting tool to follow-up the rulings issued in France and to document the characteristics of the related proceedings |

Ministry of Justice |

| Initiate the creation of a working group in charge of designing and provisioning of information tools suitable for professionals and people involved |

Health/Justice Interministerial Committee |

Article original

PÉNALISATION DE LA TRANSMISSION DU VIH : GARANTIR UNE PROCÉDURE ÉQUITABLE

Où en est-on aujourd’hui en France sur la pénalisation de la transmission de VIH ? Le professeur Patrick Yéni, président du Conseil national du sida (CNS) fait le point. Interview.

In 2006, le Conseil national du sida et des hépatites virales (CNS) avait publié un premier avis sur la pénalisation de la transmission du VIH. Qu’est-ce qui vous a conduit à travailler de nouveau sur ce sujet et à publier, en 2015, un second avis ?

Patrick Yeni : Il y a la médiatisation de certains procès en France et, d’autre part, le constat sur le plan international, dans d’autres pays concernés, qu’il y avait une réflexion active sur la pénalisation de la transmission de l’infection par le VIH alors qu’en France cette réflexion semblait marquer le pas. Ce sont ces deux raisons qui nous ont conduits à retravailler sur cette question, en essayant de comprendre et de réfléchir à la façon dont les choses avaient évolué, depuis notre premier avis.

Dans l’avis de 2015, vous jugez que l’attention apportée aux enjeux juridiques, éthiques et sanitaires de la pénalisation de la transmission est faible, tant de la part des pouvoirs publics que des acteurs associatifs. Comment l’expliquez-vous ?

Nous n’avons pas de réponse claire à cela. C’est aussi pour cela que nous avons voulu reprendre cette réflexion. Si l’on se place du point de vue des pouvoirs publics et que l’on fait le bilan des affaires judiciaires — soit 23 condamnations pour transmission du VIH depuis le début de l’épidémie pour toute la France —, on peut imaginer que pour l’Etat il ne s’agit pas là d’un problème majeur national au niveau pénal, du moins sur le plan quantitatif. J’imagine que la réflexion sur la justice pénale porte prioritairement sur d’autres questions. Pour les associations de lutte contre le sida, c’est probablement plus compliqué parce que les procédures judiciaires — comme nous essayons de l’analyser dans l’avis — mettent quelque peu à mal les fondements historiques de la lutte contre le VIH. Je citerai la solidarité entre les personnes atteintes et le refus de distinguer entre des “malades victimes” qui auraient été contaminés et d’autres qui se seraient infectés. J’imagine que cette difficulté a pu introduire de l’inertie dans la progression de la réflexion. C’est justement une recommandation du CNS que d’exhorter les associations à reprendre aujourd’hui cette réflexion, parce qu’elle constitue un bras de levier pour agir sur les stigmatisations, les discriminations… et la prévention en général.

Qu’est-ce qui est condamné aujourd’hui ? Et qu’est-ce qui est condamnable sur le plan pénal ?

C’est avant tout le fait pour une personne qui se sait séropositive d’avoir transmis le VIH à un ou une partenaire alors qu’elle n’avait pas pris de mesure de prévention pour prévenir cette transmission, en l’occurrence l’utilisation de préservatif. Dans la quasi-totalité des procès en France, c’est cela qui est condamné. Nous avons eu des réflexions sur d’autres points car les juristes qui nous ont accompagnés ont expliqué que le champ de ce qui est condamnable, de ce qui pourrait représenter un délit, est sans doute plus large que celui qui est effectivement appliqué aujourd’hui.

A quoi faites-vous référence ?

Il faut raisonner sur plusieurs niveaux. Le premier critère retenu est que ce sont des personnes qui se savent séropositives. Mais c’est plus compliqué. Ainsi, d’un point de vue juridique, on ne peut assurer qu’une personne bien que ne se sachant pas formellement séropositive puisse se considérer comme séronégative alors qu’elle est engagée dans des comportements sexuels à risques, répétés. La justice peut considérer que même si elle ne sait pas de façon formelle quel est son statut, son comportement sexuel aurait du l’inciter à se considérer comme potentiellement séropositive, donc à se tester et à mettre en œuvre des moyens de prévention. Dans ce cas, l’absence de dépistage ne garantit pas l’absence de risque pénal. Le deuxième critère est qu’il faut la preuve que la personne ait transmis le VIH. Notre analyse des jugements montre que le fait d’exposer à la transmission du VIH, même sans transmission effective, peut également être pénalisé. Il y a eu des condamnations en France pour exposition au risque de transmission. Cela s’est produit dans des cas de condamnations additionnelles à des condamnations pour transmission effective, mais cela existe.

Vous estimez donc qu’on pourrait se trouver un jour avec une condamnation au seul motif du risque d’exposition à la transmission du VIH ?

Oui. Les éléments juridiques sont là. C’est, selon notre analyse, une autre possibilité d’élargissement du champ pénal. Le troisième critère est le fait que la victime ne soit pas informée de la séropositivité du ou de la partenaire. En droit pénal, le fait que la victime soit informée ou pas n’exonère pas le prévenu de sa responsabilité. On ne peut pas arguer que le partenaire était informé et qu’il a accepté de ne pas se protéger et donc qu’on ne serait pas responsable. L’information ne suffit pas.

Quatrième critère. Dans toutes les affaires aujourd’hui, la prévention des rapports sexuels est comprise comme l’usage du préservatif. C’est le préservatif qui est retenu comme la manifestation de la préoccupation face au risque de transmission. Nous ne savons pas ce qui se passera lorsqu’il y aura des procédures engagées pour transmission ou exposition concernant des personnes qui n’utilisent pas de préservatifs, mais qui sont traitées efficacement. Certains juristes nous ont expliqué que s’il y avait transmission malgré l’usage du préservatif, il s’agirait d’un cas de force majeure qui est exonératoire de la responsabilité. On ne peut pas garantir la même chose concernant le traitement. Autrement dit, avec un traitement bien suivi, une charge virale dans le sang inférieure à 20 copies, on ne peut pas garantir qu’il n’y ait pas de temps en temps un peu de VIH dans le sperme… et donc qu’une transmission soit possible même si le traitement est bien suivi, la charge virale indétectable… D’autres juristes nous disent que nous sommes, dans ce cas-là, dans une situation d’aléa, qui, elle, n’est pas exonératoire de la responsabilité. Nous devons réfléchir à cela. Il paraîtrait impensable que ce qui est une évidence en termes de santé publique aujourd’hui sur la promotion des préventions biomédicales, soit en décalage sur le plan juridique. C’est un motif d’alerte que nous mentionnons dans l’avis. Mais il est à craindre malheureusement que cette réflexion n’ait lieu que le jour où un cas de transmission concernant une personne sous traitement efficace vienne au tribunal.

Comment expliquer que le rôle du Tasp dans la protection du rapport soit reconnu en Suisse avec toutes les conséquences juridiques que cela implique et que ce même argument ne tienne pas juridiquement chez nous ?

Nous avons souhaité alerter sur ce point afin que justement les conclusions de la justice, lorsqu’elle aura à se prononcer, soient identiques aux conclusions de santé publique que nous connaissons aujourd’hui. Nous ne devons pas arriver à cette contradiction qu’une personne qui se traiterait efficacement soit condamnée parce qu’elle n’utiliserait pas le préservatif. Avec ces exemples, on voit bien l’espace assez restreint de ce qui est effectivement condamné aujourd’hui et le fait qu’il faut absolument avoir une réflexion sur le possible élargissement de ce qui est condamnable.

L’argument est souvent avancé qu’un engagement plus avant dans la pénalisation dissuaderait les personnes de faire le dépistage ?

L’avis a analysé les conséquences de la pénalisation de la transmission en matière de recours au dépistage. Toutes les études auxquelles nous avons eu accès, essentiellement étrangères, n’indiquent pas que le risque pénal lié à la connaissance de son statut sérologique conduirait à une diminution du recours au dépistage.

Vous notez le paradoxe que les recours en justice se sont développés dans un contexte de “normalisation” de la maladie. Autrement dit, les affaires ont prospéré dans les années 2000, postérieurement à la phase la plus aigüe de l’épidémie. Comment l’expliquez-vous ?

Nous avons eu des discussions à ce sujet. Certains d’entre nous étaient réticents à affirmer qu’il y avait une augmentation du nombre de cas. Une chose est sûre, nous sommes sur un chiffre bas : 23 condamnations. D’autant plus si on le rapporte aux données de l’enquête ANRS-Vespa 2. L’enquête montre qu’un peu plus d’une personne vivant avec le VIH sur dix déclare avoir été tentée de porter plainte contre la personne qu’elle estimait être à l’origine de sa contamination. Selon la même source, 1,4 % des personnes vivant avec le VIH interrogées déclaraient avoir effectivement porté plainte. Sur la base de ces chiffres, nous avons estimé un ordre de grandeur de 1 500 à 2 000 plaintes qui auraient pu être déposées au total depuis le début de l’épidémie. Nous ne savons pas pourquoi certaines plaintes ont été acceptées et d’autres pas, pourquoi certaines ont finalement été classées et d’autres ont prospéré. Nous n’avons, hélas, aucun moyen d’évaluer cela. Nous savons juste que peu d’affaires arrivent à une condamnation.

Pour répondre plus précisément, il faut prendre en compte le fait qu’il y a un délai important, parfois dix ans, entre le moment où une plainte est déposée et celui où un jugement en appel est prononcé. Dire qu’aujourd’hui nous sommes sur une augmentation du nombre de procédures, c’est possible, mais pas certain. Nous devons être prudents sur ce point. Si c’est vrai, comment l’expliquer ? Une des hypothèses, c’est qu’aux premiers temps de l’épidémie, lorsque beaucoup de monde décédait du sida, porter plainte contre une personne qui allait sans doute mourir n’avait pas grand sens. Aujourd’hui, la situation est différente. Pour des personnes, cela peut apparaître plus “logique” de le faire. Nous avançons cette hypothèse, mais aucun chiffre ne permet de la confirmer. On peut aussi regarder quels sont ceux qui portent plainte. C’est intéressant de voir que les personnes qui portent plainte et arrivent au procès ne font pas partie des groupes dits à risques où la prévalence est très forte. Par exemple, il n’y a quasiment pas de personnes migrantes parmi les plaignants. Par ailleurs, il existe aujourd’hui une judiciarisation bien plus importante de l’intime, notamment des faits sexuels, qu’elle n’existait dans le passé. Peut-être cela joue-t-il dans le fait de porter plainte plus aujourd’hui qu’il y a vingt ans.

Quels objectifs vous êtes-vous fixés en publiant ce nouvel avis ?

Tout d’abord : informer les personnes vivant avec le VIH sur les conditions dans lesquelles leur responsabilité pénale peut être engagée. Notre réflexion a surtout porté sur le fait de pouvoir contribuer à une justice équitable. Par quels moyens ? Par une sensibilisation des enquêteurs à cette question par les écoles nationales de police et de gendarmerie. Par un travail auprès des magistrats et des avocats. Il n’est pas possible que les juges aient des connaissances techniques sur les différentes maladies, nous l’admettons. De la même façon, on ne peut pas considérer aujourd’hui, au prétexte qu’on ne meure plus du sida, que l’infection par le VIH est banale. Ce n’est pas possible parce qu’il existe un contexte de représentations sociales qui en font une maladie particulière. Pour autant, la situation n’est plus la même aujourd’hui, des progrès notamment médicaux ont eu lieu. C’est très important que les magistrats et les avocats aient connaissance de cela. Nous proposons que l’Ecole nationale de la magistrature ouvre cette réflexion dans sa formation initiale, comme dans sa formation continue. Nous avons sollicité le directeur de cette école pour lui demander d’inclure une réflexion autour du VIH dans la formation des connaissances. Un problème, qui ne concerne pas que les juges, est celui de la mise à niveau des connaissances pour contribuer à une justice équitable. Un de nos souhaits est aussi de permettre de réfléchir à la position de la justice pénale. Les peines de prison ferme prédominent dans les affaires de transmission du VIH et les questions de réinsertion et de prévention de la récidive ne sont pas du tout prises en compte, alors même que la justice doit veiller à ces deux aspects dans sa démarche.

Concrètement que préconisez-vous ?

Pour le ministère de la Justice, de se doter d’une forme d’observatoire de suivi des jugements rendus, de documenter les caractéristiques des procédures. L’outil n’existe pas et nous avons dû effectuer un travail considérable pour réaliser notre nouvel avis et retrouver tous les cas ayant abouti à des condamnations. Il faut créer un comité interministériel pour qu’il travaille à la création et la mise à disposition d’outils d’information adaptés aux professionnels (policiers, avocats, magistrats) et aux personnes concernées, pour que les procédures tiennent compte des données scientifiques et médicales disponibles, pour que les médecins soient mieux informés sur le risque pénal de la transmission du VIH. C’est du travail de lobbying que nous menons, y compris auprès des associations de lutte contre le sida. Elles doivent se réapproprier cette question, sur laquelle elles étaient un peu en situation de veille. Nous devons admettre que le droit au recours à la justice est un droit des citoyens, que notre combat n’est pas contre la justice pénale, mais plutôt pour garantir une procédure équitable et prévenir le risque pénal.

Propos recueillis par Jean-François Laforgerie.

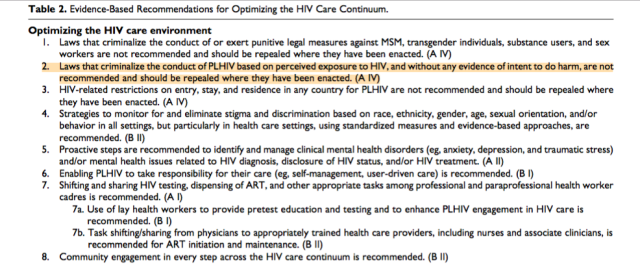

In many settings, optimizing the HIV care environment may be the most important action to ensure that there are meaningful increases in the number of people who are tested for HIV, linked to care, started on ART if diagnosed to be HIV positive, and assisted to achieve and maintain long-term viral suppression. Overcoming the legal, social, environmental, and structural barriers that limit access to the full range of services across the HIV care continuum requires multistakeholder engagement, diversified and inclusive strategies, and innovative approaches. Addressing laws that criminalize the conduct of key populations and supporting interventions that reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination are also critically important. People living with HIV also require support through peer counseling, education, and navigation mechanisms, and their self-management skills reinforced by strengthening HIV literacy across the continuum of care.

In many settings, optimizing the HIV care environment may be the most important action to ensure that there are meaningful increases in the number of people who are tested for HIV, linked to care, started on ART if diagnosed to be HIV positive, and assisted to achieve and maintain long-term viral suppression. Overcoming the legal, social, environmental, and structural barriers that limit access to the full range of services across the HIV care continuum requires multistakeholder engagement, diversified and inclusive strategies, and innovative approaches. Addressing laws that criminalize the conduct of key populations and supporting interventions that reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination are also critically important. People living with HIV also require support through peer counseling, education, and navigation mechanisms, and their self-management skills reinforced by strengthening HIV literacy across the continuum of care.