Earlier this week, I attended a meeting in Almaty, Kazakhstan, convened by UNAIDS and UN Women entitled ‘Leave No One Behind: Bringing needs and priorities of women living with HIV into policies and actions’.

Here, NGOs, community members, governments and human rights defenders from Central Asia came together to share best practices by and for women living with HIV and to cherish the leading role of women’s organisations and their contribution.

The meeting also sought to acknowledge achievements of the UNAIDS Unified Budget, Results and Accountability Framework (UBRAF) that contributes to improving the lives of women living with HIV. This was an important venue to discuss how global goals – e.g. Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS, new UNAIDS Strategy 2016-2021, and Key AIDS-Related SDGs For 2030 – are linked to local goals.

Among the meeting priorities were the focus on the leadership of women living with HIV presenting the outcomes of their UBRAF-funded projects, sharing their success stories.

In addition, networks of women living with HIV in Kazakhstan and Tajikistan presented summary results of the assessment of sustainability and fundraising competency and of the PLHIV Stigma Index, demonstrating the need for spaces for leadership and empowerment of networks, and showing where opportunities of reducing discrimination have taken place, through blogging, international campaigns, clips and photo projects.

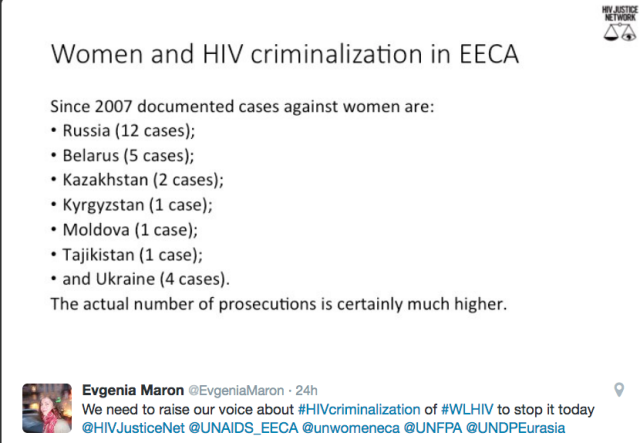

I delivered a presentation on behalf of the HIV Justice Network (HJN) on HIV criminalisation, and what women’s networks can do to challenge it, seeking to share the monitoring outcomes documented by us in the countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA).

Since 2007, we have documented over 25 criminal cases against women living with HIV for HIV alleged exposure and/or transmission, mainly in Russia, Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan. We also know about HIV-related criminalisation of marginalised groups of women in Kyrgyzstan, Moldova and Tajikistan during this period.

The actual number of prosecutions is certainly much higher.

Constituting over 50% of people living with HIV, women are seen as both victims and perpetrators in regards to HIV criminalisation, and have been impacted by criminalisation in many ways – including in their sexual relationships, violating their reproductive rights, and in the case of sex workers, being doubly criminalised for working and living with HIV.

Constituting over 50% of people living with HIV, women are seen as both victims and perpetrators in regards to HIV criminalisation, and have been impacted by criminalisation in many ways – including in their sexual relationships, violating their reproductive rights, and in the case of sex workers, being doubly criminalised for working and living with HIV.

Linking gender inequality and HIV stigma makes it obvious that women rarely have economic independence and power to make decisions about their bodies, including whether or not (male) condoms are used, and the lived experience of fear of prosecution prevents women from getting tested, knowing their status, and getting HIV treatment, because many laws are applied precisely against those who know about their diagnosis.

And there is evidence that intimate partner violence often occurs when a woman discloses her HIV status.

One of our main concerns is that the names of women arrested and prosecuted are disclosed in the media. Another is that women are usually prosecuted by their intimate male partners.

HJN has documented cases where women were prosecuted not only for alleged transmission (when the alleged transmission may have occurred from the complainant to the accused), but also for potential or perceived HIV exposure (when there may have been no exposure risk).

We need to pay special attention to prosecutions of pregnant women or for allowing vertical transmission.

We believe all of the above cases are actually the results of structural or cultural violence – these prosecutions both unjustly scapegoat individual women and justify direct violence against women living with HIV.

Alina Yaroslavska of Positive Women in Ukraine commented:

“Before HIV criminalization was not on the agenda, especially we didn’t focus on why it’s important for women, how it affects women’s lives and the epidemics as a whole. In fact, we need to gather these pieces of the puzzle. This piece is very important: on one hand, we can help people in a concrete way, on the other hand, we can take effective measure to eliminate this phenomenon. We now are forming our operational plan for the next year, and I think we will include HIV criminalization as an issue. We will meet the network of people living with HIV to join the Ukraine’s initiative to remove the corresponding criminal article. Secondly, we can include in the plan measures to support women to talk about this issue and motivate more women to join the movement for HIV Justice Worldwide.

Calling on women’s networks to work with the media, at the meeting we highlighted some media contexts, which regrettably affect the overall image of women living with HIV. Poorly written reports of such cases – without context or balance – contribute to stigma, discrimination and violence.

None of the women prosecuted had an opportunity to speak for herself, publicly. What is leading to broader devastating consequences to the women and their families is that at least half of women were subjected to public ‘slut shaming’. All of them are described in an active voice as criminals and ‘sources of infection’ in the eyes of the public health perspective is discussed, which is devastating for the future of these women.

None of the women prosecuted had an opportunity to speak for herself, publicly. What is leading to broader devastating consequences to the women and their families is that at least half of women were subjected to public ‘slut shaming’. All of them are described in an active voice as criminals and ‘sources of infection’ in the eyes of the public health perspective is discussed, which is devastating for the future of these women.

As well as introducing HIV criminalisation as an issue at the meeting, we also helped to bring a better understanding of the roots of stigma and discrimination of women living with HIV, highlighting the experiences of women’s network overseas.

On one hand, our region has badly written laws and unjust prosecutions. On the other, we don’t yet know enough about to bring about meaninful change.

By introducing HIV Justice Worldwide, and the ultimate change that we want to see as removal of discriminatory laws and practices, we are inviting organisations, advocates and communities to join us to share their experiences and learn more about successes and challenges.

The meeting was a valuable a space for dialogue, skills exchange, strategising, and networking in order to improve situation for women living with HIV in the region. Using this opportunity to talk about HIV criminalisation placed the issue within the broader context of gender, human rights, HIV, and sexual and reproductive health and rights of women.

We also discussed how we can provide rapid response and support to women criminalised under HIV-specific laws and beyond.

To think together with partners how we can focus energy and resources on creating an environment where people living with HIV can disclose their HIV status without fear of rejection, violence or discrimination is a great move towards HIV justice in the region.

With women’s networks and stakeholders, we further discussed actions required to promote implementation on HIV/AIDS and gender equality in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), notably SDG 5 – gender equality – and SDG 10 – reduced inqualities.

The need to revise and remove laws that criminalise HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission was highlighted as especially important for women living with HIV, along with introducing by law comprehensive sexual and reproductive rights and education.

The intersection of women’s rights and HIV remains an important entry point for a dialogue with governments and health authorities in Central Asia. This event had an ambitious long standing goal to address all forms of violence and harmful practices perpetrated on the basis of gender as well as prioritisation of empowerment of women and girls in developing, planning, implementing and evaluating national HIV strategic plans and policy frameworks, and, hopefully, stopping HIV criminalisation is amongst them.

Evgenia Maron is the HIV Justice Network’s EECA consultant.