On June 14, I travelled to Toronto to meet with leading activists, researchers and experts working to end the criminalization of HIV in Canada for the 8th Symposium on HIV, Law and Human Rights. Organized by the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, the annual forum for the past few years has focused solely on advocacy to end Canada’s position as a global leader in the criminalization of people living with HIV for alleged non-disclosure, exposure and transmission.

At a time when HIV has lost traction on both the political and public radar, years of dedicated advocacy to reform HIV criminalization have commanded political will to address change on this issue. This year, I felt the impact of our advocacy and the increased political will in the presence of Canada’s Minister of Justice and Attorney General the Hon. David Lametti and in the remarks that he made. Mr. Lametti opened the day with a promise to continue the process, initiated by his predecessor Jody Wilson-Raybould in 2016, to reform the “over-criminalization” of HIV. He acknowledged that the recent federal directive (which is only applicable to the territories) was not enough, further committing to engage with provinces to motivate similar directives in the provinces to address ongoing criminalization.

During the Q and A, he was pressed on the Ontario government’s recent cuts to legal aid, which will have a devastating impact on people’s right to access justice, including people living with HIV who are criminalized. Lametti promised to work to support legal aid services and also told the media afterwards that, if re-elected, he would continue reform efforts, even making HIV criminalization an election issue.

The real-life impact of criminalizing HIV non-disclosure

Following Mr. Lametti came the panel on the lived experiences of people who have been criminalized. Here, I presented outcomes from my doctoral research, where I interviewed people across Canada who had been charged or prosecuted with aggravated sexual assault due to alleged HIV non-disclosure. Many of these individuals are now registered as sex offenders. Research was also presented from the Women, ART and the Criminalization of HIV (WATCH HIV) study, revealing how women with HIV live in fear, under constant surveillance due to HIV criminalization.

During this panel session of lived experiences came the most powerful moment of the day: Michelle W., a member of the Canadian Coalition to Reform HIV Criminalization and survivor of HIV criminalization, spoke of her experiences as an Indigenous woman, surviving years of sexual abuse at the hands of men, and of her life as a former sex worker and drug user in Vancouver’s Downtown East Side. She is now a registered sex offender, having served an over two-year sentence on charges of aggravated sexual assault for alleged HIV non-disclosure. The charge came about after she fled her abusive ex-boyfriend, who then went to the police out of revenge. Michelle brought the room to tears, garnering a standing ovation. Her experiences outline the vital importance of centring our advocacy efforts on lived experiences, and the need for an intersectional analysis of the issue of HIV criminalization to hold the legal system accountable for the devastating impact it has had on women, particularly Indigenous women.

Canada “one of the worst in the world”

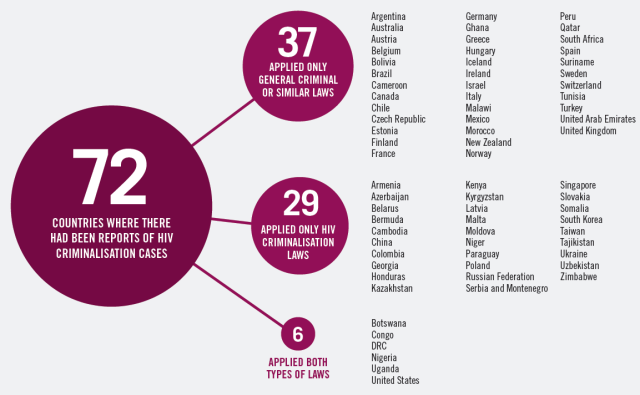

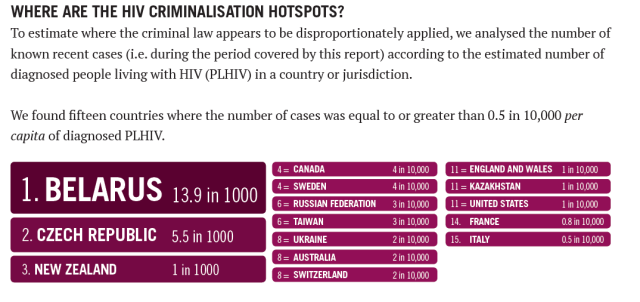

A particularly eye-opening moment during the day was when Edwin Bernard, global coordinator for the HIV Justice Network, presented an overview of the global environment of HIV criminalization. He mentioned his own fears of the distinctively harsh context in this country, noting that as someone living with HIV, he feels scared when visiting from the United Kingdom that he could become subject of our harsh laws. He further stated, “Canada’s criminalization context for people living with HIV remains one of the worst in the world.” But he also said that activism here is mobilizing for change in inspiring and pioneering ways.

To address next steps for changing our global distinction and the ongoing harms of the criminal law, further sessions focused on how to achieve legislative reform, as well as the consequences of changing the current legal approach. This included discussions of removing the laws of sexual assault from being applied to cases of HIV non-disclosure, meaning that the sex offender registry would no longer be a mandatory outcome of prosecutions.

Next steps and potential pitfalls

Discussions also focused on the double-edged sword of mobilizing science for legal reform. Science has so far helped to inform reform efforts, such as the recommendation that criminal laws no longer be applied to people who have an undetectable viral load. However, this has the potential to turn viral suppression into a dividing line for criminalization, opening the door to further marginalize and criminalize people without (or with limited) access to medication coverage, such as migrants and homeless people.

A further complication with reform efforts is that a shift away from criminal laws may mean a greater reliance on public health authorities, who are also known to apply coercive and stigmatizing practices. This might mean intensified forms of surveillance of people living with HIV, such as mandatory viral load reporting, and the increased use of public health legislation to mandate treatment.

The week after we met, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights released their report on the criminalization of HIV non-disclosure. The report included a major positive recommendation, to remove HIV non-disclosure from the laws of sexual assault ̶ This development was many years in the making. However, the report also asks for a new law to be developed, one that would apply to all communicable diseases. There’s still more work to do.

Strategizing collectively has been a success of the movement to reform HIV criminalization in Canada, one of the inspiring things about Canada’s response that Bernard noted in this presentation. In the end, this symposium helped to continue to strengthen and galvanize our work to change Canada’s heinous distinction as a global leader in criminalizing our community.

Author: Alexander McClelland