Amsterdam, Netherlands

July 26, 2018

Introduction

Good morning.

Hello everyone. I hope everyone is doing well this morning.

I would like to thank the International AIDS Society for inviting me. It is my honour to represent Canada among such a distinguished group.

We have a lot to talk about, and we also have a lot to learn.

Central to this are the perspectives and lived experience of people living with and affected by HIV and AIDS.

To those of you who have chosen to share your stories today — thank you.

You exemplify what it means to be “anti-fragile”.

You turned your challenges into strength.

I am inspired by your determination, courage and resilience.

Over the past 30 years, we have come a long way.

Thanks to the dedication and passion of people like you, we have made once unthinkable progress toward a world without AIDS.

I am proud to say that Canada has been at the forefront of this response, through the work of our civil society as well as such extraordinary champions as Stephen Lewis, Dr. Julio Montaner and, of course, Dr. Mark Wainberg. Sadly, Dr. Wainberg is no longer with us and we keenly feel his loss at this conference.

I also want to acknowledge the invaluable global contribution of people living with HIV.

Together, we have achieved a great deal. But we still have more to do.

Many people still don’t know their status, face barriers to treatment, and lack the support they need to live healthy, active lives.

Despite our efforts, something is getting in the way.

I have spoken with many people living with HIV in my time as Canada’s Minister of Health, including during my time here this week.

And while I have heard of the many struggles faced, one thing I’ve heard repeated is that stigma is holding us back.

Stigma is a significant barrier

Stigma has many faces.

We all know about HIV-related stigma, but it is compounded by other forms of stigma.

Racism. Homophobia. Transphobia.

Stigma about mental illness.

Internalized stigma.

Discrimination against people who inject drugs and those who engage in sex work.

These are just a few of the many different faces of stigma and discrimination, which have devastating effects.

Stigma can isolate people from their intimate partners, families and communities.

Stigma can keep people from getting health care.

Stigma masks HIV …and helps fuel the AIDS epidemic worldwide.

We need to stop stigma in all its forms to ensure that all people living with HIV know their status and get the treatment they need.

A rights-based approach

So, what’s the solution? A key part of the answer lies at the intersection of human rights and public health.

Treatment alone is not enough. Fighting stigma requires an integrated approach — one that puts human rights first.

In Canada, protecting and promoting human rights is part of the social fabric of our country — and it’s essential to the way we govern.

As such, human rights guide our response to HIV in Canada and abroad.

We are working to rebuild trust with marginalized communities.

While this is an ongoing process, we’ve already taken significant steps.

One key priority is renewing our “Nation-to-Nation” relationship with Canada’s Indigenous peoples — a process based on a recognition of rights, cooperation and partnership.

Another priority is LGBTQ2 rights. In November 2017, our Prime Minister formally apologized to the LGBTQ2 community for a history of federal legislation, policies and practices that were oppressive and discriminatory.

Last summer, we passed a law that prohibits discrimination against transgender Canadians and protects them against hate crimes.

We have also made significant changes to Canada’s drug policy to recognize the needs of people who use drugs.

In 2016, we restored harm reduction to the core of public health approach to the opioid crisis.

We also introduced the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act to provide some legal protection for individuals who seek emergency help during an overdose.

We hope this Act will help reduce fear of police attending overdose events and encourage people to help save a life.

Recently, we led the charge at the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs to address stigma towards people who use drugs.

Along with nineteen of our allies, we passed a resolution that stresses the importance of fighting stigma and ensuring that no one is denied health care because of it.

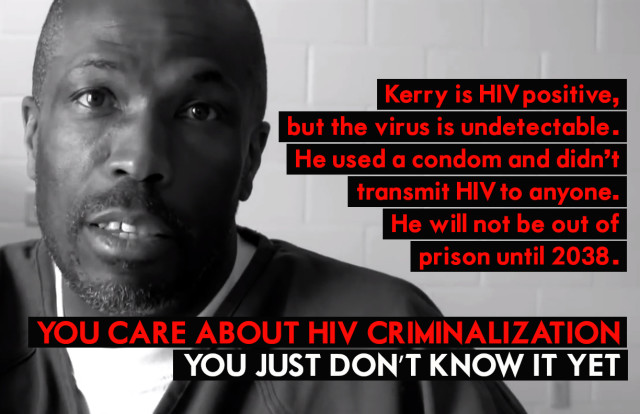

Finally, we have taken steps to prevent the criminalization of HIV non-disclosure.

We know that – U=U. Undetectable = Untransmittable. This means that there is effectively no risk of sexual transmission of HIV when an individual is being treated and maintains a suppressed viral load.

Having considered the evidence, the Government of Canada has determined that the criminal law should not apply to individuals engaging in sexual activity without disclosing their HIV status, if they maintain a suppressed viral load.

My colleague, the Minister of Justice, is working with her provincial counterparts towards addressing the criminalization of HIV.

Because we know that HIV criminalization is a manifestation, and driver, of stigma.

As such, the Government of Canada welcomes the work undertaken by experts to develop the Expert Consensus Statement on the Science of HIV in the Context of the Criminal Law which was released yesterday, and supports its conclusions that more caution be exercise when considering criminal prosecution.

The U=U message needs to be heard and has to be shared.

We have a responsibility to do reduce stigma in all its forms.

I challenge my fellow ministers of health to share this message in their respective countries.

STBBI Framework

Canada’s response to HIV takes an integrated approach involving sexually transmitted and blood borne infections, which share common risk factors and transmission routes.

Just last month, Canada launched a new Pan-Canadian Framework for Action on Sexually Transmitted and Blood-Borne Infections.

This Framework will help guide our collective efforts, including our annual investment of more than $87.5 million to reduce these infections.

Meeting our targets

At the heart of this framework are the globally recognized 90-90-90 targets.

I was happy to report on Canada’s progress just last week. Good news – Canada has achieved one of our global targets and are making progress toward the other two.

Based on 2016 data, it was estimated that just over 63,000 people are living with HIV in Canada.

Of these cases, we estimate that 86% have been diagnosed, 81% are being treated and, of these, 91% are achieving viral suppression.

I’m proud of our progress — but I know that we still have work to do to achieve our goals.

We need to get to 90 across the board, and our government supports a number of initiatives to help us get there.

For example, the Know Your Status initiative in Saskatchewan has been successful in promoting HIV testing in Indigenous communities using culturally appropriate models and is showing it is possible to decrease new diagnoses in these communities.

Other important initiatives are supported by our National Microbiology Laboratories, which work with Indigenous partners to make culturally appropriate HIV testing accessible in Canada’s rural and remote communities — which if you know anything about our country’s geography, is no small challenge.

We are also supporting efforts to address stigma and discrimination in the health sector through the development of resources and training for front-line health providers to help them provide safe — non-stigmatizing —services for people living with or at risk for HIV.

International contribution

As we take action at home, we are also looking beyond our borders and supporting the global response to HIV and AIDS.

We have and will continue to support the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

We have pledged $804 million over three years, which will help ensure people with HIV and AIDS have access to the treatment they need, no matter where they live.

I am proud that our Government supports these and other initiatives— but I also recognize these alone are not enough.

We need to keep sharing knowledge and, most importantly, we need to engage in a meaningful dialogue with people living with HIV and AIDS.

Nothing about us without us

That’s why we support organizations like the Canadian Positive People Network, a group that represents people living with HIV in Canada.

Partnerships like this help facilitate dialogue between policy makers, health care providers and people living with HIV.

As we move forward, we also have to ensure that our work is guided by the voices of youth leaders. I had the great pleasure yesterday of meeting with a group of brilliant, inspired youth from around the world.

Young people: You are the global champions in the fight against stigma, not just for the future, but for today. We need your passion, your engagement and your inspiration… to get to 90 90 90, and then to end this epidemic, for good.

Moving ahead together

We have an opportunity to elevate that conversation — to explore challenges and share solutions.

Everyone has a role to play.

Together, we can build more inclusive societies by ending stigma, prejudice and discrimination.

I wish you fruitful discussions today.

Thank you very much and enjoy the rest of the conference!

From: Public Health Agency of Canada