This statement was issued by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the HIV Medicine Association (HIVMA) on the urgent need to repeal or modernize HIV-specific criminalization statutes and laws criminalizing transmission or exposure to sexually transmitted infections and other communicable diseases.

Nigeria passes law to stop discrimination related to HIV | UNAIDS

The President of Nigeria, Goodluck Jonathan, has signed a new antidiscrimination bill into law that protects the rights and dignity of people living with HIV.

The HIV/AIDS Anti-Discrimination Act 2014 makes it illegal to discriminate against people based on their HIV status. It also prohibits any employer, individual or organization from requiring a person to take an HIV test as a precondition for employment or access to services.

It is hoped that the new law will create a more supportive environment, allowing people living with HIV to carry on their lives as normally as possible. More than three million people are living with HIV in Nigeria.

Quotes

“This is good news coming from the President to Nigerians living with HIV. We appreciate this unprecedented development, as it will help halt all HIV-related stigma and discrimination in the country and improve the national response.”

“The signing of the antidiscrimination law by the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria is a much welcome action in the fight against AIDS. It will help more Nigerians to seek testing, treatment and care services without fear of facing stigma and discrimination.”

“By signing the antistigma bill into law, the Government of Nigeria, under the leadership of President Jonathan, has given to all Nigerians living with or affected by HIV a guarantee to access justice and to regain their human rights and dignity in society while enjoying productive lives. Zero discrimination is the only environment conducive to ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030.”

UK: Law Commission scoping consultation deadline this week; key findings and outputs from ‘Criminalizing Contagion’ seminar series may help inform the process

This week, the Law Commission – which reviews areas of the law in England and Wales that have become unduly complicated, outdated or unfair – will conclude its scoping consultation of the reform the Offences Against The Person Act, the law that is currently used to prosecute people living with HIV (and occasionally other sexually transmitted infections; one each so far for gonorrhoea, hepatitis B and genital herpes) for ‘reckless’ or ‘intentional’ transmission, as grievous bodily harm.

The deadline for responses is this Wednesday 11 February 2015.

The consultation is a scoping review – it is looking at the scope of whether a further full review of the existing law should take place, rather than examining what the law should be.

The consultation asks six key questions (out of 38) specifically relating to HIV (and STI) criminalisation:

- We consider that future reform of offences against the person should take account of the ramifications of disease transmission. Do consultees agree?

- We also consider that in such reform consideration should be given to: (1) whether disease should in principle fall within the definition of injury in any reforming statute that may be based on the draft Bill; (2) whether, if the transmission of sexual infections through consensual intercourse is to be excluded, this should be done by means of a specific exemption limited to that situation. This could be considered in a wider review; alternatively (3) whether the transmission of disease should remain within the offences as in existing law. Do consultees agree?

- If the transmission of disease is to be included in any future reform including offences causing injury, it will be necessary to choose between the following possible rules about the disclosure of the risk of infection, namely: (1) that D should be bound to disclose facts indicating a risk of infection only if the risk is significant; or (2) that D should be bound to disclose facts indicating a risk of infection in all circumstances; or that whether D was justified in exposing V to that risk without disclosing it should be a question for the jury in each particular case. Do consultees have any preference as to these possible rules?

- We consider the reform of offences against the person should consider the extent to which transmission of minor infections would be excluded from the scope of injury offences. Do consultees agree?

- Do consultees consider that future reform should pursue the possibility of including specialized offences of transmission of infection, endangerment or non-disclosure?

- Do consultees have observations on the use of ASBOs, SOPOs or other means of penalizing non-disclosure?

Responses to the scoping consultation, including those from the HIV Justice Network, will be published soon. Following the consultation, the Law Commission will decide on their recommendations for the scope of reform in this area and present them to Government in the form of a scoping report.

In the meantime, the summary of key findings and outputs from the Economic and Social Research Council’s seminar series ‘Criminalizing Contagion: legal and ethical challenges of disease transmission and the criminal law’, which took place at the Universities of Southampton and Manchester from January 2012 until September 2014, provides a comprehensive legal and academic overview regarding how the law should treat a person who transmits, or exposes others to the risk of, a serious infection such as HIV.

Written jointly by David Gurnham, Catherine Stanton and Hannah Quirk, the report provides a detailed overview of the discussions in the seminars as well as the numerous publications arising from them, and acknowledges contributions made by various groups and individuals.

South Africa: Forced or involuntary disclosure in healthcare settings disproportionately affecting women resulting in discrimination and gender-based violence, despite constitutional protections

Editor’s note: This story is part of a Special Report produced by The GroundTruth Project called “Laws of Men: Legal systems that fail women.” It is produced with support from the Ford Foundation. Reported by Tracy Jarrett and Emily Judem.

An HIV diagnosis is no longer a death sentence, thanks to advances in medicine and treatment in the last 30 years. But stigma against HIV/AIDS and fear of discrimination still run strong in South Africa, despite legal protections, as well as drastically improved treatment, prevention techniques and education. Today an estimated 19 percent of South African adults ages 15-49 are living with HIV.

And women, who represent about 60 percent of people living with HIV in South Africa, face a disproportionately large array of consequences, including physical violence and abuse.

“Upon disclosure of women’s HIV positive status,” reads a 2012 study by the AIDS Legal Network on gender violence and HIV, “women’s lives change, due to fear and the continuum of violence and abuse perpetrated against them.”

Although forced or involuntary disclosure of one’s HIV status — along with any discrimination that may result from that disclosure — was made illegal by South Africa’s post-apartheid constitution, experts and advocates say that public knowledge of these laws is limited and the legal system is not equipped to implement them.

Not only are women disproportionately affected by HIV, but they are also more likely to know their status. More women get tested, said Rukia Cornelius, community education and mobilization manager at the NGO Sonke Gender Justice, based in Johannesburg and Cape Town, because unlike men, women need antenatal care.

And often, she said, clinics give women HIV tests when they come in for prenatal visits.

The way hospitals and clinics are set up also are not always conducive to protecting privacy, said Alexandra Muller, researcher at the School of Public Health and Family Medicine at the University of Cape Town.

“People who provide services in the public system, at the community level, are community members,” said Muller. “This is an important dynamic when we think about stigma and disclosure.”

Doctors and nurses can see 60 to 80 patients per day in an overcrowded facility with shared consultation rooms, Muller said.

“There’s not a lot of consideration for how is a clinic set up,” added Cornelius, so that “a health care worker who has done your test and knows your status doesn’t shout across the room to the other health care worker, ‘okay, this one’s HIV-positive, that file goes over there.’”

Once HIV-positive women disclose their status, willingly or not,they are disproportionately affected by stigma because of the direct link between HIV and gender violence.

[Feature] Beyond Blame: Challenging HIV Criminalisation

Beyond Blame: Challenging HIV Criminalisation

A pre-conference meeting for AIDS 2014

In July 2014, at a meeting held to just prior to the International AIDS Conference in Melbourne, Australia around 150 participants from all regions of the world came together to discuss the overly broad use of the criminal law to control and punish people living with HIV – otherwise known as ‘HIV criminalisation’.

The meeting was hosted by Living Positive Victoria, Victorian AIDS Council/Gay Men’s Health Centre, National Association of People Living with HIV Australia and the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations, with the support of AIDS and Rights Alliance of Southern Africa, Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, Global Network of People Living with HIV, HIV Justice Network, International Community of Women Living with HIV, Sero Project and UNAIDS.

The meeting was financially supported by the Victorian Department of Health and UNAIDS.

This highlights video (12 mins, 50 secs) was directed, filmed and edited by Nicholas Feustel, with interviews and narration by Edwin J Bernard. The video was produced by georgetown media for the HIV Justice Network.

Download the highlights video from:http://vimeo.com/hivjustice/beyondblame

Below is a feature story based on the transcript of the highlights video, with additional links and information. You can also read Felicita Hikuam’s excellent (and remarkably quickly-written) summary of the day in ‘Mujeres Adelante’ and Daniel Reeders’s impressive collection of tweets from the meeting.

FEATURE STORY

A day to come together, find solutions, and move forward

Paul Kidd: On behalf of Living Positive Victoria, the Victorian AIDS Council, Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations, and the National Association of People with HIV Australia, welcome to Beyond Blame: Challenging HIV Criminalisation. We hope today’s event is inspiring and productive and that it kicks off the discussion about HIV criminalisation that will continue through the week and beyond.

Edwin Bernard: I think this is the largest HIV Criminalisation Pre-Conference to date at an International AIDS Conference. So the idea of the meeting is to bring people together. People who are working on this issue, who are interested in learning more about it, and we’re going to really work hard to come together, find solutions, and move forward.

Julian Hows: GNP+ has been involved in this issue of criminalisation since 2002, 2003, when we noticed an increase in the rates of prosecution in Europe effectively and started the first scan of the 53 signatory countries of the European Convention on Human Rights.

This has since become the Global Criminalisation Scan, an international ‘clearing-house’ of resources, research, and initiatives on punitive laws and policies impacting people living with HIV.

Jessica Whitbread: And ICW are really, really excited to be here and part of this. Criminalisation is a huge issue for us. Over 50% of people living with HIV are women and many of these laws initially and still continue to be created as a way to protect women when actually they put us more at risk.

Getting the criminal law changed and out of the HIV response

The meeting began with a surprise announcement by the Minister of Health for Victoria, David Davis, about Australia’s only HIV-specific criminal law, Section 19A of the Victorian Crimes Act. Read more about the campaign to reform the law here.

David Davis: And as a further step in our efforts to reduce the impact of HIV and reduce stigma and discrimination, the coalition government will amend section 19A of the Crimes Act 1958 to ensure that it is non-discriminatory.

Following the announcement Victoria’s Shadow Health Minister, Gavin Jennings, committed to removing (and not just amending) Section 19A within the next 12 months, should Labor win the state election in November.

A keynote address by the Honourable Michael Kirby, a former Justice of the High Court of Australia, and a member of the Global Commission on HIV and the Law, reminded us why an overly broad criminal justice apporach to prevention does more harm than good.

Michael Kirby: In the big picture of this great world epidemic, the criminal law has a trivial role to play. What is most important is getting the law changed and out, not getting the law into the struggle against HIV and AIDS.

The Iowa example: laws are subject to change and should be subject to change

The meeting then focused on Iowa in the United States where both law reform and judicial rulings have limited the overly broad use of the criminal law.

Matt McCoy: You know, in Iowa, we had a very bad law on the books, but it’s not unlike a lot of other places in the country in the United States and in the world. So there was no need for transmission, and with it, the penalty was so extreme, a mandatory lifetime sex offender registry and 25 years in prison.

Watch the video that Senator McCoy showed at the meeting explaning how law reform in Iowa happened.

Sean Strub: Iowa is a conservative farm-belt state. And the effort there began with a small group of people with HIV who started organising others with HIV and educating their own communities and then educating public health officials and reframing the issue in terms of a public health issue rather than simply an issue of justice for people with HIV. Last month, we held a conference at Grinnell College in Grinnell, Iowa. It was the first national conference on HIV criminalisation in the US. The Friday before our conference began, Governor Branstad in Iowa signed a criminalisation reform measure and made Iowa the first state in the United States to subtantively reform and modernise their statute.

Two videos of the HIV Is Not A Crime conference (also known as the Grinnell Gathering) are available. One shows the opening ceremony and can be viewed on the Sero website. A second video highlights the voices of US HIV criminalisation survivors featured at the meeting, and can be viewed on the Sero website.

Nick Rhoades: About a week after the conference was over, the timing was just a little bit off, nonetheless, it’s fantastic. My conviction was overturned by the Iowa Supreme Court. Yeah. Thank you… It’s kinda groundbreaking, their decision, and I, first of all, think that it’s going to have an effect beyond Iowa’s borders, but it basically said that there has to be more than a theoretical chance of transmission to be prosecuted under the law. And previously, that’s not been the case. Basically, it was just if you didn’t disclose, and you had sex, that that would be enough to convict someone. So, for the first time, they basically said that factors such as using protection, being on antiretroviral medication, having an undetectable viral load specifically, should affect whether or not prosecution is able to happen.

Senator McCoy took the opportunity to urge parliamentarians to rethink how they treat HIV in a criminal context.

Matt McCoy: Many of these laws went into effect in the United States during the AIDS crisis and the scares that society had around the issue, and in many cases they were put into effect using a one-size-fits-all measure. And so this is a great opportunity to go back and to revisit that and to realise that our laws are subject to change and should be subject to change.

Science can change laws and limit prosecutions

A number of countries in Europe have also recently revisited their criminal laws, policies or practices. A poster, Developments in criminal law following increased knowledge and awareness of the additional prevention benefit of antiretroviral therapy, presented at AIDS 2014 by the HIV Justice Network, showed where and how this has taken place.

Edwin Bernard: We have to salute the Netherlands, the very first place in the world that actually, way before the Swiss statement, between 2004 and 2007, managed to change the application of the law through a variety of Supreme Court rulings, but also because of advocacy that happened with advocates and healthcare workers and people in the community who limited the role of the criminal law to only intentional exposure or transmission. Denmark was the only country in Western Europe that had an HIV-specific criminal law, and a huge amount of advocacy went on behind the scenes and that law was suspended in 2011 based on the fact that the law was about a serious, life-threatening illness, and the reality was that in Denmark, people living with HIV have exactly the same life expectancy as people without HIV. And so the law just couldn’t apply anymore. And so, we hope that the places like Denmark and the Netherlands will provide inspiration for the rest of us.

Urgent need to focus on global South

But with two-thirds of all HIV-specific criminal laws enacted in the global South, there is now an urgent need to re-focus our efforts.

Patrick Eba: For a long time, we have been saying that there is no prosecution happening in the Global South, particularly in Africa, because we were lacking the information to be able to point to those instances of criminalisation. In fact, there is a lot of prosecution that is happening, and in the past year, if you look at the data that is being maintained by the HIV Justice Network, it is clear. We’ve seen the case in Uganda. We know of a decision that came out some time late last year in South Africa. We know of a number of cases in Kenya, in Gabon, in Cameroon [and especially in Zimbabwe]; and these really show that where we celebrate and are able today to know what is happening in the Global North, our lack of understanding of the situation in the Global South is one that requires more attention.

Dora Musinguzi: Uganda is right now grappling with lots of human rights and legal issues, and it’s going to be such a high climb to really convince our governments, our people, government agencies to make sure that we really have this reform of looking at HIV from a human rights angle, public [health] angle, gender justice angle, if we are going to achieve the gains that we have known to achieve as a country. …But we stand strong in this, we are not giving up. We are looking to a future where we shall challenge this criminalisation, and we hope to come back with a positive story.

Workshops on advocacy messages, science and alternatives to a punitive criminal justice approach

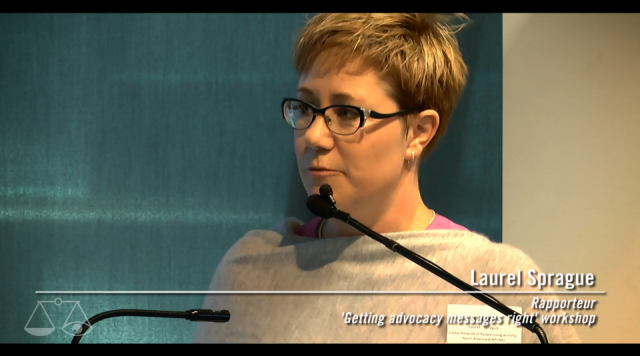

After the morning plenary sessions, participants then attended one of three workshops. The first workshop explored how to get advocacy messages right, in terms of what arguments need to be delivered by whom and to whom.

Laurel Sprague: We talked about the importance of stories. In particular, the stories of people who have been prosecuted, both because of the dignity it gives them to be able to share their own experience, and also because what we’re seeing is so broadly understood to be disproportionate once the details come out.

Laurel’s rapporteur notes can be downloaded in full here. For an example of advocacy messagaging aimed at communities impacted by HIV see this video from Queensland Positive People.

A second workshop highlighted the way that up-to-date science on HIV-related risks has limited the application of the criminal law in Sweden and Canada.

David Mejia-Canales: Really mobilising their scientists, their researchers and really connecting with the lawyers, the judiciary, the prosecutors and putting to them the best evidence that they have.

Download the Powerpoint presentation given by Cecile Kazatchine of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network here.

The third workshop examined alternatives to a punitive criminal justice system approach, and the risks and benefits of using, for example, public health law or restorative justice.

Daniel Reeders: So if someone shows up at a police station or talks to their doctor about being exposed or infected with HIV, a restorative justice approach would talk about giving them an opportunity to work that issue through with the person who they are otherwise trying to report, either for criminal prosecution or public health management. It acknowledges that people experience HIV infection as an injury and that there is a lack of a process offering them an opportunity to heal.

Daniel’s entire rapporteur report can be read on his blog.

Going home with more ideas and tools and inspiration to continue our work

As the meeting came to a close participants appreciated the day as a rare and much needed opportunity to discuss advocacy strategies.

Paul Kidd: What a day! It is just so amazing to be in this room with all of these incredible people and the sense you have of how much passion and energy and commitment there is around this issue.

Richard Elliott: Even as we face numerous setbacks in our own context sometimes, we see that in fact people are making breakthroughs elsewhere and then that helps us put pressure domestically on decision makers, on legislators, on judges.

Michaela Clayton: It’s important to learn from how people have achieved successes and what have been peoples’ problems in achieving successes in different countries in addressing criminalisation. So for us it’s a wonderful opportunity to learn from others.

Dora Musinguzi: I was encouraged to know that the struggle is not only for us in Africa, in Uganda, and I was also encouraged to know that our colleagues have made progress, and so we can.

Sean Strub: I think everywhere that there is an effort for this advocacy for reform, it is a constantly evolving effort. And the fact that the HIV Justice Network and others brought together this global community which is incredibly mutually supportive. I think of any aspect of the epidemic, I can’t think of an area where there is more collegiality and mutual respect than those of us who’ve centered our work around criminalisation reform. That’s what we’re seeing here in Melbourne, just an expansion of that, and all of us going home with more ideas and tools and inspiration to continue our work.

To remain connected with the global advocacy movement against overly broad HIV criminalisation, like us on Facebook, follow us on Twitter and sign the Oslo Declaration on HIV Criminalisation to join our mailing list.

Venezuela: National Assembly unanimously passes new rights-based law that protects people living with HIV from discrimination in all areas of life

On August 14th, the National Assembly (NA) of Venezuela passed a set of laws that, among other functions, ensure the rights of people carrying the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and their families. The Law on Protection of People with HIV will aim to prevent discrimination and provide health care to AIDS patients as well as those who are HIV positive. “This law is born of the living history of these patients and family, who suffers discrimination he faced, he had no right to health, education, work, sport, recreation, housing, vehicle, and this law lay that story they told us the family and patients, “ said Vice President of the Permanent Commission for Integrated Social Development, Henry Ventura. (from http://lainfo.es/en/2014/08/14/venezuela-will-protect-people-with-hiv/)

The bill guarantees HIV-positive people equal conditions in terms of the right to work and hold public office, to education, healthcare, culture and sports, the benefits of social programmes, bank loans, confidentiality about their health status and respect for their prívate lives. It also states that having AIDS cannot be grounds for the suspension of paternity rights, while establishing that families are responsable for caring for and protecting people living with HIV.

The law guarantees equality for young people, because 40 percent of new cases are in the 15-24 age group. It also does so in the case of women, for whom it orders that special care be provided during pregnancy, birth and the postpartum period, as well as for people with disabilities and prisoners. The bill establishes penalties, disciplinary measures and fines for those found guilty of discrimination.

The idea is to prevent a repeat of situations such as one faced by a schoolteacher in a city in western Venezuela, who remains anonymous at her request. She was fired after a campaign against her was mounted by parents who discovered that she had gone to the AIDS unit in a hospital to undergo exams. However, the miliary and the police are exempt from the protective provisions against discrimination.

“We do not agree with that exception,” Estevan Colina, an activist with the Venezuelan Network of Positive People, told IPS. “No one should be excluded and we hope for progress on that point when parliament’s Social Development Commission studies it and it goes to the plenary for the second debate,” which will be article by article.

Nieves is confident that the second reading will overturn the military-police exception. But more important, said the head of ACCSI, “is the positive aspect of the law, starting with the unanimous acceptance of a human rights issue by political groups that are so much at loggerheads in Venezuela’s polarised society.”

The law, which NGOs and activists expect to pass this year, will give a boost to anti-AIDS campaigns. The support will be similar in importance to that given by a July 1998 Supreme Court ruling that ordered public health institutions to provide free antiretrovial treatment to all people living with HIV.

India: Supportive, protective HIV law introduced in the Rajya Sabha (upper house)

Bill to end HIV/AIDS discrimination introduced – A bill aiming to protect people with HIV/AIDS against discrimination was introduced in the Rajya Sabha Tuesday. The HIV/AIDS (Prevention and Control) Bill 2014 was introduced in the upper house amid din.

The draft of the bill was finalised in 2006, and civil society groups and HIV/AIDS-affected people have long been demanding passage of the draft legislation. Under the proposed law, HIV/AIDS-affected people will be provided protection against discrimination in employment, healthcare, education, travel and insurance, in both public as well as private sectors.

The bill proposes imprisonment and fine for those spreading hatred and discrimination against HIV patients. According to official information, a fine up to Rs.10,000 and two years’ imprisonment has been proposed as punishment for spreading hatred against people with HIV/AIDS.

The bill also proposes a legal commitment to provide Anti-Retroviral Therapy (ART) by the government to the patients as far as possible.

Switzerland: New handbook for parliamentarians on effective HIV laws includes case study and interview with Green MP Alec von Graffenried

A new publication from the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), written by Veronica Oakeshott, is an excellent new resource to help inform advocacy efforts to remove punitive laws and policies that impede the HIV response.

Aimed at parliamentarians, ‘Effective Laws to End HIV and AIDS: Next Steps for Parliaments’ (aussi disponible en français) is a practical handbook showing which types of laws are helpful and unhelpful in the HIV response, and provides examples of legislation from around the world that have been effective in limiting new HIV infections.

It also includes case studies and interviews with some of the parliamentarians involved in law reform, most notably with Swiss MP Alec Von Graffenried whose last minute amendment resulted in the new Law on Epidemics containing a clause that only criminalised intentional disease transmission.

Other case studies highlighted in the handbook include: decriminalisation of sex work in New Zealand; decriminalisation of personal drug use in Portugal; ending discrimination against people living with HIV in Mongolia: and legal recognition for transgender and intersex people in South Africa.

The Swiss Law on Epidemics was finally passed, following a national referendum, in September 2013. However, it won’t come into effect until January 2016.

Below is the section explaining how and why the Swiss law reform process took place. It’s an excellent example of how advocates saw an opportunity to work with clinicians, scientists and key parliamentarians in order to make a difference. It also shows that the law reform process can be a slow and complex undertaking. Patience here is definitely a virtue.

Switzerland: Decriminalisation of unintentional HIV transmission and exposure

Name of act

The Epidemics Act 2013

Summary

Repeals and replaces the old Epidemics Act and in doing so, changes Article 231 of the Swiss Penal Code, which in the past has been used to prosecute people living with HIV for transmission and exposure, including cases where this was unintentional. The changes mean that a prosecution can only take place if the motive of the accused is to infect with a dangerous disease. Therefore, there should be no further cases for negligence or cases where the motive was not malicious (i.e. normal sexual relationships).

Why the law is important for HIV

Criminalization of HIV transmission, exposure or non-disclosure creates a disincentive for testing and gives non-infected individuals false confidence that they will be informed of any infection. In reality, their partner may not even know his or her HIV status and everyone should be responsible for protecting their own sexual health. The latest scientific findings have shown that people on HIV treatment who have an undetectable viral load and no other sexually transmitted infections are not infectious. Such people may want to have consensual unprotected sex. Criminalizing them for doing so has no positive public health impact and is an intrusion into their private life. UNAIDS is calling for the repeal of all laws that criminalize non-intentional HIV transmission, non-disclosure or exposure.

How and why was decriminalization of HIV transmission and exposure introduced in parliament?

In 2007, the Swiss Government decided to revise the Swiss law on epidemics. This was not an HIV-specific law and the decision to review it was not HIV-related but due to concerns that Switzerland was not well-placed to deal with other global epidemics, such as severe acute respiration syndrome (SARS) and H1N1. However, HIV campaigners and persons working in public health saw an opportunity to insert a clause into the Act that would amend Switzerland’s current Penal Code, Article 231 of which has been used to prosecute people living with HIV for transmission and exposure. Since 1989, there have been 39 prosecutions and 26 convictions under Article 231 in combination with the Swiss law on “grievous bodily harm”.

In December 2007, the government began a consultation on a draft Epidemics Bill and campaigners proposed a clause in it amending Article 231 of the Penal Code. In 2010, the government introduced the draft Bill into parliament. However, HIV campaigners were not happy with the new Bill as tabled and campaigned for changes throughout its passage through parliament. Improvements to the Bill were made at the Committee stage but it was not until the final vote at the National Council in 2013 that a last-minute amendment was tabled by Green MP Alec von Graffenried, which achieved campaigners’ core aim of decriminalizing unintentional transmission or exposure.

Was cross-party support secured and, if so, how? How was a majority vote secured?

The last-minute amendment was tabled and passed with 116 votes to 40. The key arguments made in favour of the amendment centred on the unsuitability of public health law to deal with private criminal matters. This rather theoretical argument appealed to legislators, many of whom are practising lawyers or have a legal background. However, the wider case for decriminalization had been made to parliamentarians over a period of many years inside and outside parliament and was reinforced by new sci- entific announcements and court decisions. MPs across the political divide realized that HIV is no longer a death sentence, but a manageable condition and that the right treatment can reduce an individual’s infectiousness to zero. In this context, MPs were more open to the idea of legal change.

During the campaigning period of many years, different arguments were made to appeal to different MPs across the political spectrum. Those on the right often responded best to the notion of an individual’s responsibility to protect their own sexual health and those on the left responded better to public health arguments. Efforts were also made to lobby the head of health departments at the regional level, who were then able to communicate their support for the change to colleagues at the national level.

How long did it take to pass the law?

It took almost six years from the consultation on the first draft of the Bill until it was confirmed by referendum in September 2013. The law will come into effect in January 2016.

Read and/or download the entire publication below.

Effective Laws to End HIV and AIDS: Next Steps for Parliaments. Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2013

Research agenda into the public health impact of overly broad HIV criminalisation highlights five areas where researchers and advocates can collaborate

A newly published report suggests a number of concrete ways that research into the impact of overly broad HIV criminalisation on public health can move the policy agenda forward, and help reform laws and create better policies for people living with HIV and most affected communities.

The report is the result of an international workshop on HIV Prevention and the Criminal Law held in Toronto, Canada on April 27th and 28th 2013 that also led to the creation of the HIV Justice Network’s video documentary, More Harm Than Good.

The workshop’s aim was to support, encourage and further develop emerging research on the public health implications of criminalising HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission. It was the first international meeting focused exclusively on sharing, critiquing and strengthening new empirical research on this topic.

The report explores three key themes that arose over the course of workshop discussions – (1) the relationship between research and advocacy; 2) the implications of HIV-related criminalisation for public health practice; and (3) the potential and limits of public health research for criminal law reform – and offers suggestions for new directions for future research on the public health implications of criminalizing HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission.

Workshop discussions emphasised that research on the public health implications of HIV-related criminalisation is able to do the following:

- Identify the impacts of HIV-related criminalisation on HIV prevention, care, treatment and support. Research into such impacts is especially important in light of new approaches that respond to the HIV epidemic by increasing the uptake of HIV testing and counselling, linking HIV-positive people to health and social services, initiating HIV antiretroviral therapy as early as possible, and retaining people living with HIV/AIDS in medical care.

- Elucidate the influence of criminalising HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission on the attitudes, opinions, beliefs and activities of people living with HIV/AIDS, people and communities at risk, service providers in public health and clinical settings and staff in ASOs and community-based organisations.

- Inform efforts to respond to the potential discriminatory enforcement of criminal laws by identifying the demographic patterns associated with HIV-related criminal prosecutions.

- Provide public health authorities with evidence required to become more engaged in the issue, to develop policy and programmes, and to comment publicly on an increasingly important facet of the HIV epidemic.

- Identify legal, ethical and practice issues faced by public health and clinical staff as a result of HIV criminalisation, and provide evidence to support legally and ethically sound policy and practice.

- Assess the efficacy and costs and benefits of different policy options to address HIV transmission.

- Inform decisions by legislators, criminal prosecutors and courts in a number of jurisdictions.

The meeting identified five main suggestions for moving the research field forward.

1. Explore novel analytical and methodological approaches

Given the complexity of HIV criminalisation, applied and theoretical research agendas should be structured broadly, inquire into a wide range of possible “implications” and account for the intersectionality of factors such as race, class, migration, colonisation and gender. New research would benefit from a deeper engagement with socio-legal studies and criminology.

Further suggestions:

- Ground research questions in a health and human rights or an intersectional/anti-oppression framework as alternatives to a public health implications framework.

- Critically engage with mainstream feminist analysis that supports HIV criminalisation.

- Use qualitative approaches, including narrative analysis, ethnographic methods and participatory action research to:

- Capture issues of importance to, and respond to the needs of, communities of people living with and at risk of HIV;

- Document and explore experiences of people who have been criminally charged and/or prosecuted as well as those who have brought forward police complaints;

- Explore HIV criminalisation as a complex, constructed and varied social phenomenon.

2. Conduct intervention research

Research on the public health implications of criminalising HIV non-disclosure would be enhanced by studies exploring the processes and outcomes of interventions that offer alternatives to criminalisation and/or that seek to prevent HIV transmission.

Further suggestions:

- Conduct research on and explore the implications of using restorative justice approaches for criminal offences related to HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission.

- Evaluate the impact of new or existing case management strategies that focus on sexual activities that risk incarceration and HIV transmission:

- Explore collaborations with HIV/AIDS Service Organisations (ASOs) and other community-based organisations as sites for intervention research. ASOs offer a less coercive and more supportive environment to address challenges of concern to the public health and the criminal justice systems;

- Conduct ethnographic research on the “Calgary Model.” (See ‘A framework to consider for the non-disclosure of HIV/AIDS – the Calgary Health Region model’ halfway down this page) The Calgary Model is a policy-informed public health case management model that has been endorsed by policy makers in Canada, yet has not been empirically studied.

3. Conduct research on factors that underpin and drive HIV criminal prosecutions

Research on the criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission has yet to rigorously explore the various factors that encourage criminal prosecutions. There has been very little research involving people who initiate criminal complaints, their motivations

for doing so, their relationships with people living with HIV/AIDS and their experience of the criminal justice system. Relatedly, we know very little about police and prosecutors, their understandings of laws related to HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission, their knowledge of HIV and HIV transmission, and their attitudes towards people living with HIV/AIDS. There is a strong need for research that explores the underlying social, structural, behavioural and cultural factors that drive HIV-related criminalisation.

Further suggestions:

- Prioritize police, prosecutors and complainants in new research.

- Conduct research on the moral and other discourses that underpin criminalization and that inform the perspectives of the general population, those living with and at risk of HIV, legislators and policy makers and those who work in the criminal justice and public health systems.

Potential research foci include:

- norms of sexual practice in communities as contrasted with principles of “good behaviour” applied by courts;

- lessons from harm reduction and drug policy reformists who have had some success in working with police in opposing drug prohibition and the “war on drugs”;

- critical analysis of how the “good versus bad” person living with HIV/AIDS is discursively constructed in media and elsewhere;

- how issues of “personal responsibility” and “wrong” conduct get constructed, expressed and enacted, and to what end;

- redesigning existing quantitative surveys to more robustly inquire into the attitudes, opinions and beliefs of respondents;

- a moral mapping and deconstruction of pro-criminalisation arguments.

4. Continue to research the implications of criminalization for those who work in HIV prevention and in clinical and support services for people living with HIV/AIDS

Additional research on how criminalisation affects the work of various practitioners engaged in HIV prevention and the treatment, care and support of people living with HIV/AIDS can further our understanding of the broad implications of criminalizing processes. Comparative studies across national jurisdictions would yield important results.

Further suggestions:

- Build on existing studies by incorporating mixed methodologies into research designs:

- Investigate innovative and more rigorous approaches to sampling than has been the case in existing studies.

- Explore how changes in front-line practice related to criminalisation may be connected with broader policy and program changes.

- Investigate the discursive and other bases of public health response (e.g. explore the origins and impact of “unwilling and unable” terminology in Canadian public health policy).

5. Conduct media research

The mass media are an important source of public information about the criminalisation of HIV non-disclosure, exposure and transmission. While we have many accounts of how the media coverage of HIV criminal cases contributes to HIV-related stigma, we have little published research that draws on rigorous sampling methods to explore this question.

Further suggestions:

- Conduct research to understand the impact of media coverage on communities and people living with and affected by HIV, the general public and legal and policy decision makers.

- Inquire into the association between media coverage and stigma especially in relation to African, Caribbean and Black communities.

- Systematically analyze the narrative and rhetorical conventions used by mainstream media when reporting on and editorialising about HIV criminal cases.

- Investigate the use of media by police as an investigative tool.

This article is only a summary of the highlights of the report, and the entire meeting report is well worth reading.

The Criminalization of HIV Transmission and Exposure Working Group from Yale University’s Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (CIRA) have also published a research agenda focused primarily on the the research needs of advocates in the United States. This was based on a meeting held in November 2011 and authored by some of the same participants that attended the Toronto workshop, including Carol L. Galletly, Zita Lazzarini and Eric Mykhalovskiy.

This meeting concluded that the research agenda should include studies of:

(1) the impact of US HIV exposure laws on public health systems and practices;(2) enforcement of these laws, including arrests, prosecutions, convictions, and sentencing; (3) alternatives to HIV exposure laws; and (4) direct and opportunity costs of enforcement.

You can read the full research agenda, originally published in the American Journal of Public Health in August 2013, below.

Criminalization of HIV Transmission and Exposure – Research and Policy Agenda (August 2013)

Global Commission on HIV and the Law Jan 2014 newsletter highlights important legal and policy developments as well as new resources

We are pleased to share this first Newsletter Issue of 2014 containing several important developments. Perhaps most significantly, there have been a number of controversial recent anti-LGBT rulings and legislation around the world. In the same week in December, both Nigeria and Uganda adopted harsh new anti-LGBT related laws, which no doubt will have repercussions on the HIV response in those countries. Also, in December in response to the Supreme Court of India’s overruling of an earlier lower court decision to strike down an anti-sodomy law, effectively recriminalizing same sex behavior, former Commissioners of the Global Commission on HIV and the Law jointly issued a statement expressing dismay at the decision of the country’s top court. On a more positive note, in October Uzbekistan lifted all restrictions on entry, stay and residence for people living with HIV – see this UNAIDS infographic on current travel restrictions for PLHIV.

Several national and local level dialogues on HIV, human rights and the law were held in recent months, including in Brazil (November), China (December), Democratic Republic of Congo (November), and Dominican Republic (June). On 28-31 October, the first Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Judicial Dialogue on HIV and the Law was held in Nairobi. Also in October, UNDP and UNAIDS organized an information session on access to affordable medicines in Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, attended by more than 30 parliamentarians. Visit our recently updated interactive map for more information on efforts by UN agencies, including UNDP and UNAIDS, in partnership with governments, civil society and international donors, to support countries in creating enabling legal environments for HIV responses and advance the findings and recommendations of the Global Commission on HIV and the Law.

A number of key knowledge products were published this past quarter, such as: Judging the epidemic: A judicial handbook on HIV, human rights and the law (UNAIDS, 2014); Protecting the rights of key HIV-affected women and girls in health care settings: A legal scan (UNDP, SAARCLAW, WAP+, 2013); HIV and human rights manual for the Democratic Republic of the Congo (French) (UNDP, 2013); Young people and the Law in Asia and the Pacific: A review of laws and policies affecting young people’s access to sexual and reproductive health and HIV services (UNESCO, UNFPA, UNAIDS, UNDP, Youth Lead, 2013); and Compendium of Judgments for Judicial Dialogue on HIV, Human Rights and the Law in Eastern and Southern Africa (UNDP, 2013).