PWN’s Barb Cardell’s webinar on Molecular HIV Surveillance and its implications for marginalized communities living with HIV, including intersections with HIV criminalization.

Canada: Review undertaken as part of government’s examination of HIV nondisclosure laws confirms risk of sexual transmission when viral load is suppressed is virtually zero

Risk of sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus with antiretroviral therapy, suppressed viral load and condom use: a systematic review

Abstract

Background: The Public Health Agency of Canada reviewed sexual transmission of HIV between serodiscordant partners to support examination of the criminal justice system response to HIV nondisclosure by the Department of Justice of Canada. We sought to determine HIV transmission risk when an HIV-positive partner takes antiretroviral therapy, has a suppressed viral load or uses condoms.

Methods: We conducted an overview and systematic review update by searching MEDLINE and other databases (Jan. 1, 2007, to Mar. 13, 2017; and Nov. 1, 2012, to Apr. 27, 2017, respectively). We considered reviews and studies about absolute risk of sexual transmission of HIV between serodiscordant partners to be eligible for inclusion. We used A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) for review quality, Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) instrument for study risk of bias and then the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the quality of evidence across studies. We calculated HIV incidence per 100 person-years with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We assigned risk categories according to potential for and evidence of HIV transmission.

Results: We identified 12 reviews. We selected 1 review to estimate risk of HIV transmission for condom use without antiretroviral therapy (1.14 transmissions/100 person-years, 95% CI 0.56–2.04; low risk). We identified 11 studies with 23 transmissions over 10 511 person-years with antiretroviral therapy (0.22 transmissions/ 100 person-years, 95% CI 0.14–0.33; low risk). We found no transmissions with antiretroviral therapy and a viral load of less than 200 copies/mL across consecutive measurements 4 to 6 months apart (0.00 transmissions/100 person-years, 95% CI 0.00–0.28; negligible risk regardless of condom use).

For full study see: http://www.cmaj.ca/content/190/46/E1350

Beyond Blame 2018 Meeting Report and Evaluation Now Available

Beyond Blame 2018: Challenging HIV Criminalisation was a one-day meeting for activists, advocates, judges, lawyers, scientists, healthcare professionals and researchers working to end HIV criminalisation. Held at the historic De Balie in Amsterdam, immediately preceding the 22nd International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2018), the meeting was convened by HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE and supported by a grant from the Robert Carr Fund for Civil Society Networks.

The Meeting Report and Evaluation, written by the meeting’s lead rapporteur, Sally Cameron, Senior Policy Analyst for the HIV Justice Network, is now available for download here.

The meeting discussed progress on the global effort to combat the unjust use of the criminal law against people living with HIV, including practical opportunities for advocates working in different jurisdictions to share knowledge, collaborate, and energise the global fight against HIV criminalisation. The programme included keynote presentations, interactive panels, and more intimate workshops focusing on critical issues in the fight against HIV criminalisation around the world.

The meeting discussed progress on the global effort to combat the unjust use of the criminal law against people living with HIV, including practical opportunities for advocates working in different jurisdictions to share knowledge, collaborate, and energise the global fight against HIV criminalisation. The programme included keynote presentations, interactive panels, and more intimate workshops focusing on critical issues in the fight against HIV criminalisation around the world.

The more than 150 attendees at the meeting came from 30 countries covering most regions of the world including Africa, Asia and the Pacific, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Latin and North America and Western Europe. Participation was extended to a global audience through livestreaming of the meeting on the HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE YouTube Channel, with interaction facilitated through the use of Twitter (using the hashtag #BeyondBlame2018) to ask questions of panellists and other speakers. See our Twitter Moments story here.

Following the meeting, participants were surveyed to gauge the event’s success. All participants rated Beyond Blame 2018 as good (6%), very good (37%), or excellent (57%), with 100% of participants saying that Beyond Blame 2018 had provided useful information and evidence they could use to advocate against HIV criminalisation.

A video recording of the entire meeting is available on HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE’s YouTube Chanel.

Key points

- The experience of HIV criminalisation was a poor fit for individual’s actions and the consequences of those actions, particularly where actions included little or no possibility of transmission or where courts did not address scientific evidence

- The consequences of prosecution for alleged HIV non-disclosure prior to sex are enormous and may include being ostracised, dealing with trauma and ongoing mental health issues, loss of social standing, financial instability, multiple barriers to participation in society, and sex offender registration

- Survivors of the experience shared a sense of solidarity with others who had been through the system, and were determined to use their voices to create change so that others do not have to go through similar experiences

- Becoming an advocate against HIV criminalisation is empowering and helps to make sense of individuals’ experiences

- The movement against HIV criminalisation has grown significantly over the last decade but as the movement has grown, so has understanding of the breadth of the issue, with new cases and laws frequently uncovered in different parts of the world.

- As well as stigma, there are multiple structural barriers in place enabling HIV criminalisation, including lags in getting modern science into courtrooms and incentives for police to bring cases for prosecution.

- Community mobilisation is vital to successful advocacy. That work requires funding, education, and dialogue among those most affected to develop local agendas for change.

- Criminalisation is complex and more work is required to build legal literacy of local communities.

- Regional and global organisations play a vital role supporting local organisations to network and increase understanding and capacity for advocacy.

- There have already been many advocacy successes, frequently the result of interagency collaboration and effective community mobilisation.

- It is critical to frame advocacy against HIV criminalisation around justice, effective public health strategy and science rather than relying on science alone, as this more comprehensive framing is both more strategic and will help prevent injustices that may result from a reliance on science alone.

- There have been lengthy delays between scientific and medical understanding of HIV being substantiated in large scale, authoritative trials, and that knowledge being accepted by courts.

- Improving courts’ understanding that effective treatment radically reduces HIV transmission risk (galvanised in the grassroots ‘U=U’ movement) has the potential to dramatically decrease the number of prosecutions and convictions associated with HIV criminalisation and could lead to a modernisation of HIV-related laws.

- Great care must be exercised when advocating a ‘U=U’ position at policy/law reform level, as doing so has the potential to deflect attention from issues of justice, particularly the need to repeal HIV-specific laws, stop the overly broad application of laws, and ensure that people who are not on treatment, cannot access viral load testing and/or who have a detectable viral load are not left behind.

- Courts’ poor understanding of the effectiveness of modern antiretroviral therapies contributes to laws being inappropriately applied and people being convicted and sentenced to lengthy jail terms because of an exaggerated perception of ‘the harms’ caused by HIV.

- HIV-related stigma remains a major impediment to the application of modern science into the courtroom, and a major issue undermining justice for people living with HIV throughout all legal systems.

- HIV prevention, including individuals living with HIV accessing and remaining on treatment, is as much the responsibility of governments as individuals, and governments should ensure accessible, affordable and supportive health systems to enable everyone to access HIV prevention and treatment.

- New education campaigns are required, bringing modern scientific understanding into community health education.

- Continuing to work in silos is slowing our response to the HIV epidemic.

- HIV criminalisation plays out in social contexts, with patriarchal social structures and gender discrimination intersecting with race, class, sexuality and other factors to exacerbate existing social inequalities.

- Women’s efforts to seek protections from the criminal justice system are not always feminist; they often further the carceral state and promote criminalisation.

- Interventions by some purporting to speak on behalf of women’s safety or HIV prevention efforts have delivered limited successes because social power, the structuring of laws and the ways laws are administered remain rooted in patriarchal power and structural violence.

- Feminist approaches must recognise that women’s experiences differ according to a range of factors including race, class, types of work, immigration status, the experience of colonisation, and others.

- For many women, HIV disclosure is not a safe option.

- More work is needed to increase legal literacy and support for local women to develop and lead HIV criminalisation advocacy based on their local context.

- When women affected by HIV have had the opportunity to consider the way that ‘protective’ HIV laws are likely to be applied, they have often concluded that those laws will be used against them and have taken action to advocate against the use of those laws.

At the end of the meeting, participants were asked to make some closing observations. These included:

- Recognising that the event had allowed a variety of voices to be heard. In particular, autobiographical voices were the most authentic and most powerful: people speaking about their own experiences. This model which deferred to those communicating personal experiences, should be use when speaking to those in power.

- Appreciating that there was enormous value in hearing concrete examples of how people are working to address HIV criminalisation, particularly when working intersectionally. It is important to capture these practical examples and make them available (noting practical examples will form the focus of the pending Advancing HIV Justice 3 report).

- Understanding that U=U is based on a degree of privilege that is not shared by all people living with HIV. It is vital that accurate science informs HIV criminalisation as a means to reduce the number of people being prosecuted, however, people who are not on treatment are likely to become the new ‘scapegoats’. It is important that we take all opportunities to build bridges between U=U and anti-HIV criminalisation advocates, to create strong pathways to work together and support shared work.

- Noting the importance of calling out racism and colonialism and their effects.

- Observing that more effort is required to better understand and improve the role of police, health care providers and peer educators to limit HIV criminalisation.

- Exploring innovative ways to advocate against HIV criminalisation, including community education work through the use of art, theatre, dance and other mechanisms.

- Concluding that we must challenge ourselves going forward. That we must make the circle bigger. That next time we meet, we should challenge ourselves to bring someone who doesn’t agree with us. That we each find five people who aren’t on our side or don’t believe HIV criminalisation is a problem and we find ways and means (including funding) to bring them to the next Beyond Blame.

Lancet editorial welcomes the recent consensus statement on science and HIV criminalisation

Canada: Study highlights how the criminal law does not consider the gendered power unbalance of HIV disclosure

Positive sexuality: HIV disclosure, gender, violence and the law—A qualitative study

Abstract

While a growing body of research points to the shortcomings of the criminal law in governing HIV transmission, there is limited understanding of how cis and trans women living with HIV (WLWH) negotiate their sexuality and HIV disclosure in a criminalized environment. Given the ongoing criminalization of HIV non-disclosure and prevalence of gender-based violence, there is a critical need to better understand the dynamics of negotiating sexual relationships and HIV disclosure among WLWH. We conducted 64 qualitative interviews with cis and trans WLWH in Vancouver, Canada between 2015 and 2017. The interviews were conducted by three experienced researchers, including a cis and a trans WLWH using a semi-structured interview guide. Drawing on a feminist analytical framework and concepts of structural violence, the analysis sought to characterize the negotiation of sexual relationships and HIV disclosure among WLWH in a criminalized setting. For many participants their HIV diagnosis initially symbolized the end of their sexuality due to fear of rejection and potential legal consequences. WLWH recounted that disclosing their HIV status shifted the power dynamics in sexual relationships and many feared rejection, violence, and being outed as living with HIV. Participants’ narratives also highlighted that male condom refusal was common and WLWH were not only subjected to the gendered interpersonal violence of male condom refusal but also to the structural violence of legislation that requires condom use but fails to account for the gendered power imbalance that shapes condom negotiation. Despite frequently being represented as a law that ‘protects’ women, our findings indicate that the criminalization of HIV non-disclosure constitutes a form of gendered structural violence that exacerbates risk for interpersonal violence among WLWH. In line with recommendations by, the WHO and UNAIDS these findings demonstrate the negative impacts of regulating HIV prevention through the use of criminal law for WLWH.

Full study is available here

US: Anti-criminalisation advocates worried about use of molecular surveillance to identify transmission clusters

Will the Genetic Analysis–Based HIV Surveillance Safeguard Privacy?

The CDC is beginning to use molecular surveillance of HIV to identify transmission clusters, which has some privacy advocates concerned.

The future of the U.S. public health system’s efforts to track and respond to the spread of HIV is called molecular surveillance. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recently begun scaling up a program to analyze genetic sequencing of newly identified cases of the virus so as to identify transmission clusters: groups of people who share strains of HIV so genetically similar that the virus likely passed among them.

Such a high-tech ability to characterize HIV’s pathway through sexual or injection-drug-use networks could open the door for local health departments to seek out individuals in such transmission webs or at risk of joining one so as to provide them tailored HIV care and treatment or prevention services.

The epidemic-battling prospects of this dawning method of epidemic surveillance notwithstanding, an ad hoc group of HIV advocates has begun to raise concerns about what they see as the potential for the misuse of personal information gleaned from the process.

Additionally, advocates point to the patchwork of laws that, depending on the state, make it a crime for people living with the virus not to disclose their HIV status, to potentially expose someone to the virus, or to transmit the virus to another individual during sex or the sharing of drug paraphernalia. At least in theory, a criminal case based on an alleged violation of such a law could prompt a subpoena for information from molecular surveillance records and ultimately allow such data to enter a court record.

Molecular HIV surveillance, or MHS, “provides an opportunity to help address growing HIV disparities but only if it is implemented responsibly and in collaboration and partnership with communities affected by and living with HIV,” says Amy Killelea, JD, director of health systems integration at NASTAD (National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors). “Because MHS activities are rolling out in states with HIV criminal transmission statutes in place, it is important for health departments, providers and anyone charged with safeguarding this data to follow procedures for prohibiting or limiting its release.”

How molecular HIV surveillance works

When an individual tests positive for HIV and connects to medical care for the virus, his or her clinician typically orders drug resistance testing, sending a blood sample to a lab that genetically sequences the virus. The results are sent to the clinician and to the local health department. Then, depending on the state, the findings may be stripped of information connecting them to a named individual and sent from the health department to the CDC for further analysis. Looking at diagnoses from the previous three years, investigators at the federal agency will search for genetic matches among these de-identified cases of the virus—HIV strains that have no more than a 0.5 percent variation, or genetic distance, between them.

The CDC is in especially hot pursuit of rapidly growing HIV transmission clusters, which the agency defines as a collection of genetically linked cases of which at least five were diagnosed within the most recent 12-month period. After identifying such a cluster, the CDC will report its findings to the health department that has jurisdiction over the majority of the related cases of the virus.

That health department may then take action, for example, by engaging in a practice known as HIV partner services: contacting members of the transmission cluster and asking for their help in tracking down others in their sexual or drug-sharing network who may have been exposed to HIV in order to urge them to get tested for the virus.

Among those individuals who test negative, health departments have an opportunity to promote HIV risk reduction, such as by prompting them to get on Truvada (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine) as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Those who test positive will ideally receive a prescription to antiretrovirals (ARVs) in short order. Immediate HIV treatment protects their health and, provided ARVs reduce their viral load to an undetectable level, renders them essentially unable to transmit the virus.

Together, PrEP and HIV treatment use among those engaging in high-risk practices can help cut the links in transmission chains and possibly avert numerous downstream infections.

On a wider scale, health departments can draw upon the findings from their investigations of transmission clusters to determine where they are coming up short in promoting HIV prevention and treatment services. They can also identify societal patterns that are facilitating HIV transmission—for example, if a lack of health care access among a particularly disenfranchised population is associated with an increased transmission rate among such individuals.

At the February 2018 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in Boston, CDC epidemiologist Anne Marie France, PhD, MPH, presented a report on the agency’s recent efforts to identify molecular clusters, depicting this technology as a prime tool for helping to determine where and among whom the virus is rapidly transmitting. The agency, she said, was recently able to identify 60 rapid transmission clusters, which included five to 42 individuals, among whom the virus was transmitted at a rate 11 times greater than that of the general population.

The members of these clusters were disproportionately men who have sex with men, in particular young Latino MSM. Gathering such demographic information is especially vital as the CDC tries to make sense of why, in the MSM population, Latinos have seen a rising HIV transmission rate in recent years while the infection rate has leveled off among their Black counterparts and continued a long decline among white MSM.

The effort to safeguard private information

The late 1990s saw the beginning of a long-running debate about the potential costs of switching to a name-based system of reporting HIV test results, in which the names of people diagnosed with the virus were kept on file by state health departments. At the time, a broad swath of advocates expressed grave concerns that that this form of surveillance would lead to privacy violations and scare people away from testing for the virus.

By and large, such fears were not borne out during the more than a decade it took for every state to switch over to name-based reporting. Instead, this recordkeeping transition proved vital in the CDC’s effort to comprehensively track the epidemic nationwide and to provide better-tailored responses.

Now HIV advocates have staked a similarly critical stance with regard to molecular HIV surveillance: that the technology’s use may lead to privacy violations and also deter people who are concerned about such outcomes from getting tested.

According to the CDC, the Public Health Service Act governs the privacy of information reported through the agency’s National HIV Surveillance System, forbidding its release for non-public-health purposes. This protection remains in effect in perpetuity, even after an individual’s death.

In response to POZ’s inquiries about molecular HIV surveillance, a CDC spokesperson stated in an email: “As a condition of funding [from the federal agency], state and city health departments must comply with strict CDC standards for HIV data security, including multiple requirements for encryption of electronic data, physical security, limited access, [personnel] training and penalties if procedures aren’t followed.”

For example, CDC policy holds that only authorized individuals should have access to information that identifies people included in molecular HIV surveillance analyses. Health agencies should print out such information only when necessary, and such hard copies should be kept under lock and key, not taken out of the health department office and shredded when they’re no longer in use.

As for the matter of how such surveillance may affect individuals’ attitudes toward getting tested for HIV, the CDC relayed to POZ findings from a recent survey of young adults never tested for the virus. When asked their main reasons for not being screened, 70 percent reported they didn’t see themselves as at risk for HIV and 20 percent said they were never offered a test. The implication is that for most people, privacy concerns may not be a major factor affecting their willingness to get tested.

Community engagement and response

In the eyes of its critics, the CDC has not properly reached out to members of the HIV community for input about the scale-up of molecular surveillance.

“I see how [molecular surveillance] could be beneficial for HIV prevention strategies in certain circumstances,” says Sean Strub, POZ’s founder and former publisher and the executive director of the Sero Project, a nonprofit that focuses on reforming HIV criminalization statutes. “But before [molecular surveillance is] utilized, the privacy and potential for abuse concerns need to be addressed in partnership with community activists.”

Addressing the CDC’s recent actions as it has pushed the rollout of molecular surveillance, David Evans, the interim executive director of Project Inform in San Francisco, says, “Meaningful engagement [by the CDC] with the communities most vulnerable to HIV has been sporadic and ineffective or completely absent in many geographic locations already. And I have yet to see concrete plans to ensure this takes place at the local, state and federal level going into the future.”

Evans and Strub were among the attendees of a recent daylong meeting about molecular HIV surveillance convened by Georgetown Law School in Washington, DC. The confab, which included CDC representatives, heard concerns that partner services programs may wind up violating individuals’ privacy, including potentially sharing their sexual orientation, as outreach workers engage in partner services efforts.

“Doing partner services successfully now takes a finesse that we have probably not developed in the staff across the country who are doing this work,” says another of the meeting’s attendees, Eve D. Mokotoff, MPH, director of HIV Counts in Ann Arbor, Michigan, which provides guidance on HIV surveillance issues nationally and internationally. “I am concerned that our country’s partner services workforce does not have the sensitivity, skill and tools needed to make them a welcome member of our prevention efforts. They too often offend clients, out them to others or otherwise are ineffective.”

Mokotoff calls for improved education of such frontline public health staff in order to ensure the highest level of professionalism, discretion and sensitivity.

As for the possibility that information acquired via molecular surveillance could be used in a criminal trial, Killelea notes the federal and state data privacy and security laws that limit health departments’ release of data except in narrow circumstances.

“This is particularly important when it comes to the release of surveillance data for law enforcement purposes,” Killelea wrote in an email, “i.e., as a result of a court order or subpoena in the course of a prosecution under a state HIV criminal transmission statute.”

“It’s important to note,” Killelea added, “that state laws vary on whether a subpoena or court order is required for health departments to release surveillance data and judges don’t necessarily need to approve a subpoena.”

A likely safeguard, Killelea says, protecting molecular surveillance information from entering a trial is that for a judge to approve a subpoena such data would have to be able to prove the direction of HIV infection—who infected whom—which in most cases the technology cannot determine. Consequently, the release of this sort of information in a courtroom setting could be “rare or nonexistent,” according to Killelea. But as this surveillance technology advances, the directionality of infection could become provable, thus undermining such a legal safeguard.

In response to such legal concerns, the CDC told POZ that the agency has “urged all state and local [health department] programs to review their own laws and policies for protection of data and to work with local policymakers to enhance protections as needed.”

In an effort to guide such state-level policy revisions, the CDC has on hand a piece of model legislation called the Model State Public Health Privacy Act. And while the federal health agency is not actively engaging in an effort to change HIV criminalization statutes, a chief document on its website regarding molecular HIV surveillance suggests that states and local jurisdictions should “consider evaluating any laws that criminalize HIV transmission” as a part of a larger effort to “minimize the risk that molecular surveillance data will be misused or misinterpreted.”

Benjamin Ryan is POZ’s editor at large, responsible for HIV science reporting. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, New York, The Nation, The Atlantic, The Marshall Project, The Village Voice, Quartz, Out and The Advocate. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter and at benryan.net.

Published in POZ on August 13, 2018

Bringing Science to Justice: End HIV Criminalisation Now

News Release

Networks of people living with HIV and human rights and legal organisations worldwide welcome the Expert Consensus Statement on the Science of HIV in the Context of Criminal Law

Amsterdam, July 25, 2018 — Today, 20 of the world’s leading HIV scientists released a ground-breaking Expert Consensus Statement providing their conclusive opinion on the low-to-no possibility of a person living with HIV transmitting the virus in various situations, including the per-act transmission likelihood, or lack thereof, for different sexual acts. This Statement was further endorsed by the International AIDS Society (IAS), the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (IAPAC), the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and 70 additional experts from 46 countries around the world.

The Expert Consensus Statement was written to both assist scientific experts considering individual criminal cases, and also to urge governments and criminal justice system actors to ensure that any application of the criminal law in cases related to HIV is informed by scientific evidence rather than stigma and fear. The Statement was published in the peer-reviewed Journal of the International AIDS Society (JIAS) and launched at a critical moment during the 22nd International AIDS Conference, now underway.

“As long-time activists who have been clamouring for a common, expert understanding of the current science around HIV, we are delighted with the content and widespread support for this Statement,” said Edwin J Bernard, Global Co-ordinator of the HIV Justice Network, secretariat to the HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE campaign. “Eminent, award-winning scientists from all regions of the world have come together to provide a clarion call for HIV justice, providing us with an important new advocacy tool for an HIV criminalisation-free world.”

The Statement provides the first globally-relevant expert opinion regarding individual HIV transmission dynamics (i.e., the ‘possibility’ of transmission), long-term impact of chronic HIV infection (i.e., the ‘harm’ of HIV), and the application of phylogenetic analysis (i.e., whether or not this can be used as definitive ‘proof’ of who infected whom). Based on a detailed analysis of scientific and medical research, it describes the possibility of HIV transmission related to a specific act during sexual activity, biting or spitting as ranging from low to no possibility. It also clearly states that HIV is a chronic, manageable health condition in the context of access to treatment, and that while phylogenetic results can exonerate a defendant when the results exclude them as the source of a complainant’s HIV infection, they cannot conclusively prove that one person infected another.

“Around the world, we are seeing prosecutions against people living with HIV who had no intent to cause harm. Many did not transmit HIV and indeed posed no actual risk of transmission,” said Cécile Kazatchkine, Senior Policy Analyst with the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, a member and key partner organisation of the HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE campaign. “These prosecutions are unjust, and today’s Expert Consensus Statement confirms that the law is going much too far.”

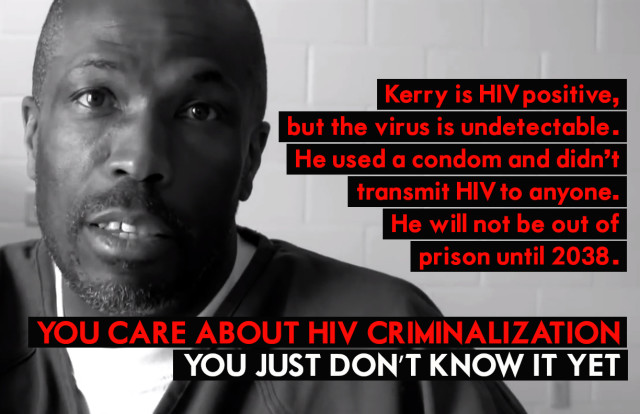

Countless people living with HIV around the world are currently languishing in prisons having been found guilty of HIV-related ‘crimes’ that, according the Expert Consensus Statement, do not align with current science. One of those is Sero Project Board Member, Kerry Thomas from Idaho, who says: “I practiced all the things I knew to be essential to protect my sexual partner: working closely with my doctor, having an undetectable viral load, and using condoms. But in terms of the law, all that mattered was whether or not I disclosed. I am now serving a 30-year sentence.”

While today’s Statement is extremely important, it is also crucial to recognise that we cannot end HIV criminalisation through science alone. Due to the numerous human rights and public health concerns associated with HIV criminalisation, UNAIDS, the Global Commission on HIV and the Law, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, and the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health, among others, have all urged governments worldwide to limit the use of the criminal law to cases of intentional HIV transmission. (These are extremely rare cases wherein a person knows their HIV-positive status, acts with the intention to transmit HIV, and does in fact transmit the virus.)

While today’s Statement is extremely important, it is also crucial to recognise that we cannot end HIV criminalisation through science alone. Due to the numerous human rights and public health concerns associated with HIV criminalisation, UNAIDS, the Global Commission on HIV and the Law, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, and the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Health, among others, have all urged governments worldwide to limit the use of the criminal law to cases of intentional HIV transmission. (These are extremely rare cases wherein a person knows their HIV-positive status, acts with the intention to transmit HIV, and does in fact transmit the virus.)

We must also never lose sight of the intersectional ways that — due to factors such as race, gender, economic or legal residency status, among others — access to HIV treatment and/or viral load testing, and ability to negotiate condom use are more limited for some people than others. These are also the same people who are less likely to encounter fair treatment in court, within the medical system, or in the media.

“Instead of protecting women, HIV criminalisation places women living with HIV at increased risk of violence, abuse and prosecution,” says Michaela Clayton, Executive Director of the AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa (ARASA). “The scientific community has spoken, and now the criminal justice system, law and policymakers must also consider the impact of prosecutions on the human rights of people living with HIV, including women living with HIV, to prevent miscarriages of justice and positively impact the HIV response.”

HIV criminalisation is a pervasive illustration of systemic discrimination against people living with HIV who continue to be stigmatised and discriminated against on the basis of their status. We applaud this Statement and hope it will help end HIV criminalisation by challenging all-too-common mis-conceptions about the consequences of living with the virus, and how it is and is not transmitted. It is indeed time to bring science to HIV justice.

To read the full Expert Consensus Statement, which is also available in French, Spanish and Russian in the Supplementary Materials, please visit the Journal of the International AIDS Society at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jia2.25161

VIsit the HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE website to read a short summary of the Expert Consensus statement here: http://www.hivjusticeworldwide.org/en/expert-statement/

To understand more about the context of the Expert Consensus Statement go to: http://www.hivjusticeworldwide.org/en/expert-statement-faq/

HIV JUSTICE WORLDWIDE is a growing, global movement to shape the discourse on HIV criminalisation as well as share information and resources, network, build capacity, mobilise advocacy, and cultivate a community of transparency and collaboration. It is run by a Steering Committee of ten partners – AIDS Action Europe, AIDS-Free World, AIDS and Rights Alliance for Southern Africa (ARASA), Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network, Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+), HIV Justice Network, International Community of Women Living with HIV (ICW), Southern Africa Litigation Centre (SALC), Sero Project, and Positive Women’s Network – USA (PWN-USA) – and currently comprises more than 80 member organisations internationally.

UK: Avon & Somerset police withdraw untrue claims that HIV could be contracted through spitting

Police finally change false HIV claims after being accused of ‘preying on people’s prejudices’

Avon and Somerset Police falsely claimed that HIV could be transferred through saliva

Bristol’s police force has finally changed untrue claims it made about HIV, eight months after it was accused of “preying on people’s prejudices.”

Avon and Somerset Police announced last November that it would be rolling out controversial spit hoods to be used on suspects to protect officers.

But during the announcement, the force made untrue claims that HIV could be contracted through spitting, causing outrage amongst campaign groups.

The force did apologise for “any offence caused” to anyone living with HIV, but then repeated the claim that Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) can be transferred through spit.

Now eight months after police made the claim, Avon and Somerset Constabulary has now confirmed that HIV will not be used as a reason to introduce spit guards after national guidance was changed.

Assistant Chief Constable Steve Cullen said: “I’d like to thank both charities and our communities for the advice and feedback they gave us following our announcement last year.

“We apologised unreservedly at the time if we caused any offence to people living with HIV.

“It has never been our intention to reinforce stigma. Every day we work to reduce stigma and discrimination experienced by communities and individuals who are victims of hate crime in all its guises.”

In January, 2018 Bristol Live reported that Avon and Somerset Police said the false claims about the transfer of HIV were taken from national guidlines.

The Bristol wing of the HIV advocacy group ACTup! Launched a petition calling for the force to retract the statement.

A spokesperson for the group said officers deserve not to be spat at while working and the group is not calling for the recall of spit hoods but raised issues with the “poorly researched” press announcement.

ACC Cullen added: “Our aim has never been to focus attention on people living with health conditions, but to target people who use spit as a weapon.

“We assured our communities we would seek to ensure that we learn from this and would share our learnings across the police service, providing clarity and direction.

“We also invited Brigstowe to help support our training for officers and staff

“I’m delighted that this has now been done.”

The National Police Chiefs Council, which issues guidance to police forces across the UK, said in January the advice on spit guards has not changed since it published a report in March 2017, but specific guidance on HIV was sent to police forces after feedback was received by Avon and Somerset.

The police chiefs’ council guidance on spit guards released in March last year said the national picture for blood-borne viruses like HIV affecting officers was “unclear “.

HIV is found in many bodily fluids of a sufferer including semen, vaginal and anal fluids, blood and breast milk.

The disease is most commonly contracted through unprotected sex and the sharing of needles. NHS England states HIV cannot be contracted through saliva.

Spit hoods made of mesh are shaped like a plastic bag and are put over the heads of suspects who had threatened to spit, have attempted to spit or have spat before.

UK: New research confirms HIV cannot be transmitting through spitting and risks from biting are negligible

HIV cannot be transmitted by spitting, and risk from biting is negligible, says detailed case review

Use of spit hoods not justified to protect emergency workers from HIV

There is no risk of transmitting HIV through spitting, and the risk from biting is negligible, according to research published in HIV Medicine.

An international team of investigators conducted a meta-analysis and systematic review of reports of HIV transmission attributable to spitting or biting. No cases of transmission due to spitting were identified and there were only four highly probable cases of HIV being transmitted by a bite.

The study was motived by the use of spit hoods by police forces in the UK because of the perceived risk of the transmission of HIV and other blood-borne viruses from spitting. The researchers’ findings endorse the position of the National AIDS Trust and Hepatitis C Trust that neither HIV nor hepatitis C virus can be transmitted by spitting, and that the use of spit hoods by police forces to protect offices against these viruses cannot be justified.

“We undertook a systematic literature review of HIV transmission related to biting or spitting to ensure that decisions about future policy and practice pertaining to biting and spitting incidents are informed by current medical evidence,” explain the study’s authors.

They identified published studies and conference presentations reporting on transmission of HIV via spitting or biting. Inclusion criteria were: discussion of transmission by biting or spitting; outcome described by documented HIV antibody test. Two reviewers independently identified studies that were included in the full analysis.

There were no cohort or case-control studies. The investigators therefore assessed the plausibility of HIV being transmitted to a spitting or biting incident according to baseline HIV status, nature of the injury, temporal relationship between the incident and HIV test, and where, available, phylogenetic analysis.

The plausibility of transmission being related to an incident was categorised as high, medium or low.

A total of 742 studies and case reports were reviewed by the authors.

There were no reported cases of HIV transmission attributable to spitting.

A total of 13 studies reported on HIV transmission and biting. The studies consisted of eleven case reports and two case series relating to HIV transmission, or its absence, after a biting incident.

None of the possible cases of HIV transmission due to biting were in the UK or involved emergency workers. The reports included information on 23 individuals, of whom nine (39%) seroconverted for HIV. Six of these cases involved family members, three involved fights resulting in serious wounds, and two were the result of untrained first-aiders placing fingers in the mouth of an individual experiencing a seizure.

“Of the 742 records reviewed, there was no published cases of HIV transmission attributable to spitting, which supports the conclusion that being spat on by an HIV-positive individual carries no possibility of transmitting HIV,” write the authors. “Despite biting incidents being commonly reported occurrences, there were only a handful of case reports of HIV transmission secondary to a bite, suggesting that the overall risk of HIV transmission from being bitten by an HIV-positive person is negligible.”

There were only four highly plausible cases of HIV transmission resulting from a bite. In each case, the person with HIV had advanced disease and was not on combination antiretroviral therapy and was therefore likely to have had a high viral load. The bite caused a deep wound and the HIV-positive person had blood in their mouth.

“Two cases occurred in the context of a seizure whereby an untrained first-aid responder was bitten while trying to protect the seizing person’s airway,” note the researchers. “It is therefore important that both emergency workers and first-aid responders are trained in safe seizure management including non-invasive airway protection and use universal precautions.”

The investigators emphasise that they found no cases of an emergency worker or police officer being infected with HIV because of a bite. They point out that bite injuries are a common reason for attending accident and emergency departments: a review of A&E admissions over a four-year period at a hospital in the United Kingdom found that one person was admitted with a bite wound every three days, on average.

“Current UK guidance on indications for PEP [post-exposure prophylaxis, emergency HIV therapy after a high-risk exposure to HIV] state that ‘PEP is not recommended following a human bite from an HIV-positive individual unless in extreme circumstances and after discussion with a specialist,’” conclude the authors. “Necessary conditions for transmission of HIV from a human bite appear to be the presence of untreated HIV infection, severe trauma (involving puncture of the skins), and usually the presence of blood in the mouth of the biter. In the absence of these conditions, PEP is not indicated, as there is no risk of transmission.”

Reference

Cresswell FV et al. A systematic review of risk of HIV transmission through biting or spitting: implications for policy. HIV Med, online edition. DOI: 10.1111/hiv.12625 (2018).

Published in aidsmap on May 8, 2018

Canada: Recent case in British Columbia demonstrates the "cycle of fear, stigma and misinformation surrounding HIV"

Misinformation is the real culprit in British Columbia HIV case

Police and media left out key details of HIV non-disclosure charges –

The case of Brian Carlisle shows that when it comes to HIV, what you don’t know can hurt you.

Last summer, Mission RCMP reported that Carlisle, a 47-year-old marijuana activist, had been charged with three counts of aggravated sexual assault for not disclosing to his sexual partners that he has HIV. The RCMP posted Carlisle’s name and photo, asking for any other partners who might have been exposed to come forward.

At the time, the RCMP said that while they would not normally publish private medical information, “the public interest clearly outweighs the invasion of Mr Carlisle’s privacy.”

Xtra does not usually publish the names of people charged with HIV non-disclosure, but Carlisle has given permission to Xtra to publish his name and HIV status.

In the following months, three charges of aggravated sexual assault against Carlisle swelled into 12.

But the RCMP failed to mention a crucial fact: Carlisle couldn’t transmit the virus to anyone.

After studying thousands of couples over decades of research, HIV scientists around the world have reached the consensus that people with HIV who regularly take medication and achieve a suppressed viral load cannot transmit the virus through sexual contact. Like most HIV patients in British Columbia, Carlisle’s viral load was suppressed, so none of the women he had sex with were in any danger of contracting the virus.

Months after publicly disclosing his HIV status, Crown prosecutors stayed all charges against Carlisle. But it became stunningly clear that not only had the police not fully informed the public that Carlisle was uninfectious, they also hadn’t properly informed Carlisle’s alleged victims.

One woman who had sex with Carlisle told the CBC anonymously about going through PTSD, anxiety and depression, losing her job and going bankrupt because she thought she might have HIV.

Not only did the woman mistakenly think she could have contracted HIV, she also said she thought she still might become infected. Nine months after charges were laid against Carlisle, she told the CBC she still had to “wait one more year to know if I have HIV or not,” and that she was still taking HIV tests every three months to ensure the virus did not appear. She said she still avoids sexual relationships out of fear of having to disclose that she might have HIV.

This understanding of how HIV testing works is catastrophically wrong. Modern HIV testing technology, like that used by the BC Centre for Disease Control, catches 99 percent of new HIV infections only six weeks after a new infection. If even that window is too large, new technologies like RNA amplification, also used in BC, can cut the time down to only two weeks.

Even if Carlisle’s viral load had been high enough to transmit the virus, which it was not, the women he had sex with could have been given a clear bill of health only days after the RCMP knocked on their doors.

The CBC, however, did not correct the woman’s misinformation, and reported as fact that the women involved would have to undergo annual testing to make sure they do not have HIV.

Mission RCMP would not confirm at what point they discovered that Carlisle’s viral load was suppressed, or when they informed the women involved, because they say the investigation into Carlisle is still open. It’s also not clear who told the women they might be infected, or that they required yearly HIV testing.

Regardless what you think of Carlisle’s choice not to inform his sexual partners that he had HIV, and regardless whether you care about the publication of his name and HIV positive status, much of the psychological harm suffered by the women in Carlisle’s case was for nothing. Accurate medical information might have saved them months or years of anxiety, fear and isolation.

Carlisle’s case is an example of what many HIV experts say is a cycle of fear, stigma and misinformation surrounding HIV, propelled by police and prosecutors’ use of the criminal law against people who are HIV positive. Criminal prosecutions, experts say, make people less likely to seek medical help or get tested, and can increase the likelihood of new infections. One study found thathalf of the targets of HIV non-disclosure prosecutions are Black men, and nearly 40 per cent are men with male partners.

Media reports in other high profile Canadian HIV cases have also skimmed over the medical science, adding to public confusion around HIV safety.

In December, a federal government report recommended that prosecutors should move away from the “blunt instrument” of the criminal law to handle HIV non-disclosure cases, and the government of Ontario announced it would stop prosecuting cases involving people with low viral loads. BC’s attorney general said in December he would also reconsider the province’s policy, but recent updates to the Crown counsel policy manual do not rule out prosecuting people whose viral load makes the virus intransmissible.

Regardless of the law, the least that the police and journalists can do is be honest and accurate about the actual risks involved in HIV cases. Carlisle’s case shows just how devastating ignorance can be.

Published in Xtra on May 5, 2018