Will the Genetic Analysis–Based HIV Surveillance Safeguard Privacy?

The CDC is beginning to use molecular surveillance of HIV to identify transmission clusters, which has some privacy advocates concerned.

The future of the U.S. public health system’s efforts to track and respond to the spread of HIV is called molecular surveillance. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recently begun scaling up a program to analyze genetic sequencing of newly identified cases of the virus so as to identify transmission clusters: groups of people who share strains of HIV so genetically similar that the virus likely passed among them.

Such a high-tech ability to characterize HIV’s pathway through sexual or injection-drug-use networks could open the door for local health departments to seek out individuals in such transmission webs or at risk of joining one so as to provide them tailored HIV care and treatment or prevention services.

The epidemic-battling prospects of this dawning method of epidemic surveillance notwithstanding, an ad hoc group of HIV advocates has begun to raise concerns about what they see as the potential for the misuse of personal information gleaned from the process.

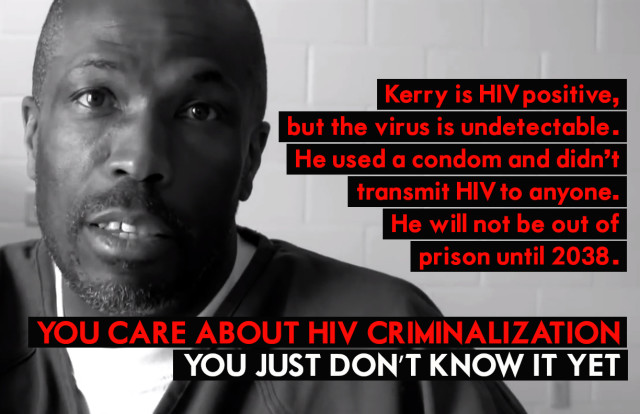

Additionally, advocates point to the patchwork of laws that, depending on the state, make it a crime for people living with the virus not to disclose their HIV status, to potentially expose someone to the virus, or to transmit the virus to another individual during sex or the sharing of drug paraphernalia. At least in theory, a criminal case based on an alleged violation of such a law could prompt a subpoena for information from molecular surveillance records and ultimately allow such data to enter a court record.

Molecular HIV surveillance, or MHS, “provides an opportunity to help address growing HIV disparities but only if it is implemented responsibly and in collaboration and partnership with communities affected by and living with HIV,” says Amy Killelea, JD, director of health systems integration at NASTAD (National Alliance of State & Territorial AIDS Directors). “Because MHS activities are rolling out in states with HIV criminal transmission statutes in place, it is important for health departments, providers and anyone charged with safeguarding this data to follow procedures for prohibiting or limiting its release.”

How molecular HIV surveillance works

When an individual tests positive for HIV and connects to medical care for the virus, his or her clinician typically orders drug resistance testing, sending a blood sample to a lab that genetically sequences the virus. The results are sent to the clinician and to the local health department. Then, depending on the state, the findings may be stripped of information connecting them to a named individual and sent from the health department to the CDC for further analysis. Looking at diagnoses from the previous three years, investigators at the federal agency will search for genetic matches among these de-identified cases of the virus—HIV strains that have no more than a 0.5 percent variation, or genetic distance, between them.

The CDC is in especially hot pursuit of rapidly growing HIV transmission clusters, which the agency defines as a collection of genetically linked cases of which at least five were diagnosed within the most recent 12-month period. After identifying such a cluster, the CDC will report its findings to the health department that has jurisdiction over the majority of the related cases of the virus.

That health department may then take action, for example, by engaging in a practice known as HIV partner services: contacting members of the transmission cluster and asking for their help in tracking down others in their sexual or drug-sharing network who may have been exposed to HIV in order to urge them to get tested for the virus.

Among those individuals who test negative, health departments have an opportunity to promote HIV risk reduction, such as by prompting them to get on Truvada (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine) as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP).

Those who test positive will ideally receive a prescription to antiretrovirals (ARVs) in short order. Immediate HIV treatment protects their health and, provided ARVs reduce their viral load to an undetectable level, renders them essentially unable to transmit the virus.

Together, PrEP and HIV treatment use among those engaging in high-risk practices can help cut the links in transmission chains and possibly avert numerous downstream infections.

On a wider scale, health departments can draw upon the findings from their investigations of transmission clusters to determine where they are coming up short in promoting HIV prevention and treatment services. They can also identify societal patterns that are facilitating HIV transmission—for example, if a lack of health care access among a particularly disenfranchised population is associated with an increased transmission rate among such individuals.

At the February 2018 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) in Boston, CDC epidemiologist Anne Marie France, PhD, MPH, presented a report on the agency’s recent efforts to identify molecular clusters, depicting this technology as a prime tool for helping to determine where and among whom the virus is rapidly transmitting. The agency, she said, was recently able to identify 60 rapid transmission clusters, which included five to 42 individuals, among whom the virus was transmitted at a rate 11 times greater than that of the general population.

The members of these clusters were disproportionately men who have sex with men, in particular young Latino MSM. Gathering such demographic information is especially vital as the CDC tries to make sense of why, in the MSM population, Latinos have seen a rising HIV transmission rate in recent years while the infection rate has leveled off among their Black counterparts and continued a long decline among white MSM.

The effort to safeguard private information

The late 1990s saw the beginning of a long-running debate about the potential costs of switching to a name-based system of reporting HIV test results, in which the names of people diagnosed with the virus were kept on file by state health departments. At the time, a broad swath of advocates expressed grave concerns that that this form of surveillance would lead to privacy violations and scare people away from testing for the virus.

By and large, such fears were not borne out during the more than a decade it took for every state to switch over to name-based reporting. Instead, this recordkeeping transition proved vital in the CDC’s effort to comprehensively track the epidemic nationwide and to provide better-tailored responses.

Now HIV advocates have staked a similarly critical stance with regard to molecular HIV surveillance: that the technology’s use may lead to privacy violations and also deter people who are concerned about such outcomes from getting tested.

According to the CDC, the Public Health Service Act governs the privacy of information reported through the agency’s National HIV Surveillance System, forbidding its release for non-public-health purposes. This protection remains in effect in perpetuity, even after an individual’s death.

In response to POZ’s inquiries about molecular HIV surveillance, a CDC spokesperson stated in an email: “As a condition of funding [from the federal agency], state and city health departments must comply with strict CDC standards for HIV data security, including multiple requirements for encryption of electronic data, physical security, limited access, [personnel] training and penalties if procedures aren’t followed.”

For example, CDC policy holds that only authorized individuals should have access to information that identifies people included in molecular HIV surveillance analyses. Health agencies should print out such information only when necessary, and such hard copies should be kept under lock and key, not taken out of the health department office and shredded when they’re no longer in use.

As for the matter of how such surveillance may affect individuals’ attitudes toward getting tested for HIV, the CDC relayed to POZ findings from a recent survey of young adults never tested for the virus. When asked their main reasons for not being screened, 70 percent reported they didn’t see themselves as at risk for HIV and 20 percent said they were never offered a test. The implication is that for most people, privacy concerns may not be a major factor affecting their willingness to get tested.

Community engagement and response

In the eyes of its critics, the CDC has not properly reached out to members of the HIV community for input about the scale-up of molecular surveillance.

“I see how [molecular surveillance] could be beneficial for HIV prevention strategies in certain circumstances,” says Sean Strub, POZ’s founder and former publisher and the executive director of the Sero Project, a nonprofit that focuses on reforming HIV criminalization statutes. “But before [molecular surveillance is] utilized, the privacy and potential for abuse concerns need to be addressed in partnership with community activists.”

Addressing the CDC’s recent actions as it has pushed the rollout of molecular surveillance, David Evans, the interim executive director of Project Inform in San Francisco, says, “Meaningful engagement [by the CDC] with the communities most vulnerable to HIV has been sporadic and ineffective or completely absent in many geographic locations already. And I have yet to see concrete plans to ensure this takes place at the local, state and federal level going into the future.”

Evans and Strub were among the attendees of a recent daylong meeting about molecular HIV surveillance convened by Georgetown Law School in Washington, DC. The confab, which included CDC representatives, heard concerns that partner services programs may wind up violating individuals’ privacy, including potentially sharing their sexual orientation, as outreach workers engage in partner services efforts.

“Doing partner services successfully now takes a finesse that we have probably not developed in the staff across the country who are doing this work,” says another of the meeting’s attendees, Eve D. Mokotoff, MPH, director of HIV Counts in Ann Arbor, Michigan, which provides guidance on HIV surveillance issues nationally and internationally. “I am concerned that our country’s partner services workforce does not have the sensitivity, skill and tools needed to make them a welcome member of our prevention efforts. They too often offend clients, out them to others or otherwise are ineffective.”

Mokotoff calls for improved education of such frontline public health staff in order to ensure the highest level of professionalism, discretion and sensitivity.

As for the possibility that information acquired via molecular surveillance could be used in a criminal trial, Killelea notes the federal and state data privacy and security laws that limit health departments’ release of data except in narrow circumstances.

“This is particularly important when it comes to the release of surveillance data for law enforcement purposes,” Killelea wrote in an email, “i.e., as a result of a court order or subpoena in the course of a prosecution under a state HIV criminal transmission statute.”

“It’s important to note,” Killelea added, “that state laws vary on whether a subpoena or court order is required for health departments to release surveillance data and judges don’t necessarily need to approve a subpoena.”

A likely safeguard, Killelea says, protecting molecular surveillance information from entering a trial is that for a judge to approve a subpoena such data would have to be able to prove the direction of HIV infection—who infected whom—which in most cases the technology cannot determine. Consequently, the release of this sort of information in a courtroom setting could be “rare or nonexistent,” according to Killelea. But as this surveillance technology advances, the directionality of infection could become provable, thus undermining such a legal safeguard.

In response to such legal concerns, the CDC told POZ that the agency has “urged all state and local [health department] programs to review their own laws and policies for protection of data and to work with local policymakers to enhance protections as needed.”

In an effort to guide such state-level policy revisions, the CDC has on hand a piece of model legislation called the Model State Public Health Privacy Act. And while the federal health agency is not actively engaging in an effort to change HIV criminalization statutes, a chief document on its website regarding molecular HIV surveillance suggests that states and local jurisdictions should “consider evaluating any laws that criminalize HIV transmission” as a part of a larger effort to “minimize the risk that molecular surveillance data will be misused or misinterpreted.”

Benjamin Ryan is POZ’s editor at large, responsible for HIV science reporting. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, New York, The Nation, The Atlantic, The Marshall Project, The Village Voice, Quartz, Out and The Advocate. Follow him on Facebook and Twitter and at benryan.net.

Published in POZ on August 13, 2018