Translated from Russian with Google translate. Scroll down for the original article.

Do you want to know how an activist living with HIV went from a public defender in cases under Article 113 of the Criminal Code to a community expert who, after speaking at a feminist forum, is influencing the humanisation of legislation on people living with HIV in Uzbekistan?

Read about it in Svetlana Moroz’s interview with Yevgeniya Korotkova on the significant reduction of the list of prohibited professions for people living with HIV in Uzbekistan.

S.M.: Zhenya, let’s start from the beginning. In 2020, a woman who faced criminal prosecution for working as a hairdresser came to your organisation for help. Tell us about this woman, why did she come to you specifically?

E.K.: I remember very well when we first started to focus on the issue of HIV criminalisation under Article 113 of the Criminal Code. At that time, we were actively collecting cases of people who had been prosecuted under this article. At some point we came across an article on the website of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. It said that an orphaned teenager living with HIV had sexual relations with a teenage girl and she became pregnant. The main message of the article was directed at parents – they should keep an eye on their children and have preventive conversations with them.

However, the article was full of stigmatising, incorrect and distorted information. Amidst the outrage, we decided to write a post on our organisation’s page, where I gave my comments. This post also included an appeal to people living with HIV who were affected by Part 4 of Article 113 of the Criminal Code of the Republic of Uzbekistan. We informed that they could contact us for legal assistance and counselling.

The response to the post did not take long. One of the first to appeal was a woman who worked as a hairdresser. She told us that her case had already been taken to court and at the time of the investigation she didn’t even have money for a lawyer. We started looking for ways to help and were able to find money to pay for a lawyer. The lawyer took on her case and filed a request to review the materials.

In the process of discussions with the woman, we came to the conclusion that I would participate in the court as a public defender from our organisation. It was the first such experience for me. We did not know that we even had the opportunity to represent someone’s interests in this way. So we prepared a motion in which we indicated that in addition to the lawyer, the interests of the woman would be represented by a public defender – that is me.

This case was a serious test for me. We discovered a new form of assistance that we had not even realised existed before.Now we know that the involvement of a public defender can be key in such cases and really helps people.

S.M.: How did this case get to court? Who sued this woman? How did they find out about her HIV status?

E.K.: How exactly this case ended up in court, we learnt only during the trial. It turned out that a police officer came to the woman’s workplace with some list. He showed her that she was on the list and said that it included people who violated the law. In particular, it was about those who were HIV-positive and worked in a hairdresser’s shop, which was allegedly against the law.

In fact, it meant the transfer of health data to law enforcement agencies without the consent of the patient. And at the trial they did not even tried to hide this fact. During the trial, the prosecutor who was in charge of the case directly stated that the information about her HIV status had been obtained from the AIDS Centre.

S.M.: How was the trial? What was the verdict?

E.K.: The trial was held in closed mode, because the case concerned doctor-patient confidentiality and confidentiality of the diagnosis. We were very lucky that we managed to attract doctors who supported our side and defended the woman.She was strictly following the ARV regimen, so she had an undetectable viral load. In court, a doctor acted as an expert who clearly explained that under such conditions, infection was impossible. He also emphasised that there were no casualties at the time of trial.

Even the investigator pointed out in the case file that the woman did not use scissors or razors in her work – only a haircutting machine. She did not use cutting or stabbing objects that could theoretically create a threat of infection. It is important to note that the witnesses who were called from her work did not testify negatively. They confirmed that the woman performed her duties professionally and without impropriety.

In my arguments, I relied on this evidence to argue that our defendant could not have transmitted HIV infection while working as a hairdresser. During the hearing, the judge asked me, ‘As a public defender, would you, yourself, have gone to this woman to cut your hair?’ I explained that HIV transmission would have required a number of unlikely conditions: she would have had to be off therapy, and she would have cut herself and me badly. Only then could there be a theoretical threat of infection. But even then, the probability of transmission would be extremely low.

I would like to note separately that the Makhali committee gave our defendant serious support. They filed many petitions in her defence, despite knowing her HIV status. The women’s committee also got involved in the process and filed additional motions in favour of our client.

However, the woman was still given a suspended sentence of two and a half years. This decision was taken because of the existence of Article 113, under which she was tried. The court took into account that she had a minor child, and this influenced the mitigation of the sentence.

I still remember how the judge, while announcing the verdict, emphasised the importance of our advocacy work. He said that our organisation should work on changing the list of prohibited professions because it contradicts modern legislation. These words were the starting point for a great advocacy process that took us three years. This case not only showed us the need to protect people in specific situations, but also gave a start to changes at the systemic level.

S.M.: How does this woman live now? How does she feel?

E.K.: You can imagine, she worked in her favourite profession for more than 30 years. It was a terrible blow for her – to lose the job on which she had built her whole life. Given that she had a minor child and was a single mother and the sole breadwinner in the family, all the responsibility fell on her shoulders. After the trial, it was very difficult for her to find a suitable job. She did everything she could: she cleaned houses, worked as a governess, tried a lot of professions.

It was not easy for her to recover from the trial. She underwent a long psychological rehabilitation, and we, on our part, also supported her by providing the services of a psychologist. This period was very difficult for her. When the legislation was finally changed, I was the first to send her the amended document. But unfortunately, she never returned to the profession. Instead, she started her own small business, determined to start her life with a clean slate.

We continued and still maintain a relationship with her. After the trial, she took part in the Judges’ Forum where she spoke openly and told her story. She shared how an unfair piece of legislation had affected her life and it was an act of courage and hope for change. She was motivated by the desire to help others who are HIV-positive so that they would no longer have to face the hardships and humiliation that she went through.

We realised that this case was not only about criminal law issues, but also touched on socio-economic rights. It showed how much stigma and restrictive laws can affect a person’s life, depriving them of a source of income and the ability to work in a profession. Nevertheless, her story has become an important part of our advocacy work and has helped draw attention to the need for change in the law.

S.M.: We have another milestone in this story – in 2022, Uzbekistan, the third country in Central Asia (after Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan) to receive, among other things, a recommendation to decriminalise HIV transmission from the UN CEDAW committee. Your country received this recommendation, largely due to your participation and our joint shadow report from the community. Can we assume that the recommendations received have influenced the advocacy process in the context of HIV decriminalisation, namely the revision of the list of prohibited professions?

E.K.: I had only three minutes to address the CEDAW Committee and I remember very well how we prepared my oral statement. Every second mattered. It seems to me that all our efforts were interconnected, especially considering how seriously the state takes the recommendations of international structures. In recent years, the country has really seen progress in supporting women.

From 2019, laws have started to be adopted to ensure equal rights for men and women and to combat discrimination and violence against women. I see that the country is emphasising women’s economic independence and expanding our educational and professional opportunities. Special attention is being paid to women’s access to leadership positions, which opens up new perspectives for us.

I believe that the final recommendations of the CEDAW Committee may have played a role in the state’s attention to the list of prohibited professions. This list has long been in need of revision, as it restricted women’s rights and hindered their professional development. The work in this direction is ongoing, and I hope that our efforts will help more women to avoid such restrictions and achieve justice.

S.M.: So, the year is 2024. Something has happened that probably you and we ourselves did not expect – the list of prohibited professions for people living with HIV in Uzbekistan has been changed (reduced) by the order of the Minister of Health. How did this become possible?

E.K.: According to the new order, HIV-positive people can now work as dentists, as long as they are not involved in surgical interventions. This move was a significant change, especially for us, as we had a case where a man working as a dental technician was prosecuted just because of his HIV status.

In November 2023, there was a big feminist forum where I gave a speech that was well received. One of the newspapers wrote about me as a leader living with HIV. After this publication, the presidential administration became interested in my story. I was invited to a meeting to discuss the most pressing issues facing women and people living with HIV.

At the meeting, I tried to use this opportunity to draw attention to the list of prohibited professions. I explained that this piece of legislation is not only of no public benefit, but also destroys people’s lives by restricting their ability to work in their profession. My arguments resonated. I had the impression that I was able to convince them that this order had long ago lost its relevance.

In the course of the discussion, it became clear that the officials with whom I spoke had a progressive approach and were ready to support the initiative to review and amend the list of prohibited professions. Their readiness for dialogue and understanding of the importance of the issue inspired me and gave me hope for further positive changes.

S.M.: Do I understand correctly that officials of the Ministry of Health had no resistance to this initiative? Before that, doctors used to hand over data on people with HIV to the police. I can’t forget the case when a woman (nurse) was simply summoned to the district department in the middle of the working day, checked the list of her contacts in the phone book, asked who she was sleeping with, threatened with an article, etc. – such ‘preventive’ humiliating methods.

E.K.: After the adoption of the new, shortened list of prohibited professions, we started to conduct trainings for medical workers. In the process, we encountered some resistance – among the participants there were epidemiologists who did not support the changes. They argued that the risk of HIV transmission still existed despite the new data and international standards. Such statements rather demonstrated their lack of awareness of the issue. Later, their colleagues, doctors with more experience, even advised them to refrain from making such statements in order not to mislead other participants.

Particularly important for us was the participation of the chief epidemiologist of the Republican AIDS Centre in these trainings. He presented information about the changes in the list of professions in the most professional and accessible way possible, which helped to reduce mistrust and resistance among health workers. His presentations played an important role in disseminating correct knowledge.

We also held meetings with the staff of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, in particular with representatives of the moral department, which supervised cases related to Article 113 of the Criminal Code. They were the ones who had previously initiated cases against HIV-positive hairdressers, leading to their criminal prosecution. These discussions were important for us because they allowed us to convey to law enforcement officials that the old norms no longer meet modern realities and only contribute to the stigmatisation of people living with HIV.

S.M.: We know that you worked on the bill that has already been submitted from your NGO Ishonch va Haet to the parliament. You have also received a response, thankfully. How do you assess the prospect of amending the Criminal Code with regard to Article 113?

E.K.: I am an optimist and I am sure that the changes will definitely happen, it is only a matter of time. It is already evident that people involved in legislative reforms realise that some laws are outdated and need to be revised. It is good to see that the country is actively aiming to update the legislative systems and bring them in line with modern realities.

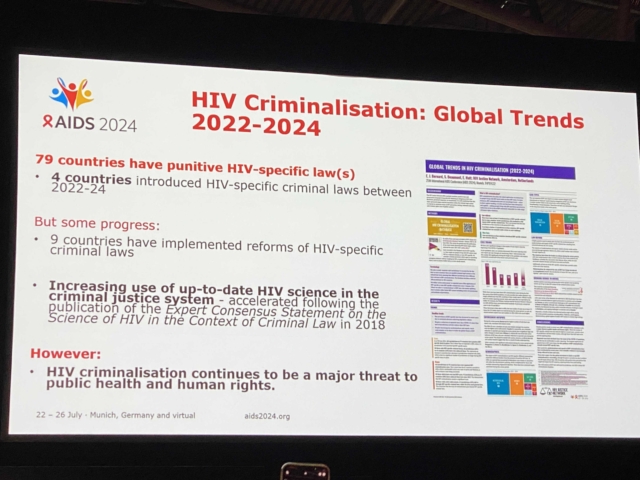

I believe that our voice will be heard. Especially since these changes are being called for not only by civil society, but also by the scientific and medical community, as well as international organisations. These are not just recommendations invented in a narrow circle of activists/v – they are a global agenda, reflecting progress and the realisation that HIV infection is now a chronic disease that can be lived with thanks to affordable and effective treatment.

Importantly, positive developments are already taking place in the country. Progressive initiatives on gender equality, protection of the rights of women and people living with HIV demonstrate the state’s commitment to improving the quality of life of its citizens. These changes give me confidence that the reform will also affect the legislative acts that still restrict people in their rights and freedom of choice of profession.

I believe in my state and its rational approach. I see that there is a dialogue going on and it is bearing fruit. We are moving towards change, and I am convinced that it will be positive for everyone.

S.M.: One last question. Looking back at your path from a public defender to a community expert who submits a draft of legislative changes to the parliament, tell us how you came to this? Who/what is behind it?

E.K.: Behind all our efforts there are always people – people who need help and support. I myself am a woman living with HIV, and although I have not experienced criminalisation directly, I have had many examples of stigma and discrimination in my life. One of the people I defended in court is now an employee of our organisation. It is stories like these that give me the strength and inspiration to keep going.

Deep down, I dream of a perfect world. No one can stop me from at least trying to make it so. My main motivation has always been to ensure that people living with HIV no longer face discrimination and stigma, that their rights are respected and not violated just because of their diagnosis.

I am convinced that the state should work in the interests of those who live in it. And today we really have good prospects.We see the existence of political will and civil society, which is actively involved in promoting change and has real weight.This is a favourable time for change.

The state is showing a desire to hear us and understand our problems. Moreover, we are not just talking about problems, we are helping to find solutions, and this process becomes an additional motivation for me. When we are listened to and really heard, it is inspiring. It means that our efforts matter and lead to change.

|

Order of the Minister of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan

On approval of the List of types of professional activities prohibited for persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus

[Registered by the Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Uzbekistan on May 07, 2014. Registration № 2581] |

Order of the Minister of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan

On approval of the List of types of professional activities prohibited for persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus

[Registered by the Ministry of Justice of the Republic of Uzbekistan on February 19, 2024. Registration № 3497] |

|

Types of professional activities prohibited for persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus

List:

1. Professions related to the procurement and processing of blood and its components.

2. Professions related to the production of blood and its components, sperm and breast milk.

3. Professions related to blood transfusion.

4. Professions related to the following medical procedures: injections; dialysis; venesection;, catheterization.

5. Professions related to cosmetic and plastic surgery.

6. Professions related to dental procedures.

7. Professions related to childbirth.

8. Professions related to abortions and other gynecological operations.

9. Professions related to hair and shaving, piercing, manicure, pedicure and tattooing. |

Types of professional activities prohibited for persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus

List:

1. Professions related to the procurement, processing and transfusion of human blood and/or its components.

2. Professions related to all types of surgery.

3. Professions related to childbirth.

4. Professions related to the following medical procedures: dialysis; venesection; catheterization. |

«К нам пришла женщина, она просила помощи с судебным процессом»

Интервью с Евгенией Коротковой

Хотите узнать, как активистка, живущая с ВИЧ, прошла путь от общественной защитницы по делам по 113-й статье Уголовного Кодекса до экспертки сообщества, которая после выступления на феминистском форуме влияет на гуманизацию законодательства в отношении людей, живущих с ВИЧ, в Узбекистане?

Читайте об этом в интервью Светланы Мороз с Евгенией Коротковой, посвященном существенному сокращению списка запрещенных профессий для людей, живучих с ВИЧ, в Узбекистане.

С.М.: Женя, давай начнем с начала. В 2020 году к вам в организацию за помощью обратилась женщина, которая столкнулась с уголовным преследованием за то, что она работала парикмахером. Расскажи про эту женщину, почему она пришла именно к вам?

Е.К.: Я хорошо помню, как мы только начали уделять внимание проблеме криминализации ВИЧ в рамках статьи 113 Уголовного кодекса. Мы тогда активно собирали кейсы людей, которые были привлечены по этой статье. В какой-то момент наткнулись на статью на сайте МВД. В ней говорилось о том, что подросток-сирота, живущий с ВИЧ, вступил в половую связь с подростком девочкой, и она забеременела. Основной посыл статьи был направлен на родителей — мол, следите за детьми и проводите с ними профилактические беседы.

Однако статья была переполнена стигматизирующей, некорректной и искаженной информацией. На фоне возмущения мы решили написать пост на странице нашей организации, где я дала свои комментарии. В этом посте также было обращение к людям, живущим с ВИЧ, которые пострадали по части 4-й статьи 113 УК РУз. Мы сообщали, что они могут обратиться к нам за юридической помощью и консультациями.

Реакция на пост не заставила себя долго ждать. Одной из первых обратилась женщина, работавшая парикмахером. Она рассказала, что ее дело уже передано в суд, а на момент расследования у нее даже не было средств на адвоката. Мы начали искать возможности помочь и смогли найти деньги на оплату адвокатских услуг. Адвокатка взялась за ее дело и подал запрос на ознакомление с материалами.

В процессе обсуждений с этой женщиной мы пришли к выводу, что я буду участвовать в суде как общественная защитница от нашей организации. Это был для меня первый такой опыт. Мы не знали, что у нас вообще есть возможность представлять чьи-то интересы таким образом. И мы подготовили ходатайство, в котором указали, что помимо адвоката интересы женщины будет представлять общественная защитница — то есть я.

Этот случай стал для меня серьезным испытанием. Мы открыли для себя новую форму помощи, о существовании которой раньше даже не догадывались. Теперь мы знаем, что участие общественного(ой) защитника/цы может оказаться ключевым в подобных делах и реально помогает людям.

С.М.: Как это дело попало в суд? Кто подал в суд на эту женщину? Как они узнали о ее ВИЧ статусе?

Е.К.: То, как именно это дело оказалось в суде, мы узнали только в ходе судебного процесса. Оказалось, что к женщине на работу пришел сотрудник милиции с каким-то списком. Он показал ей, что она числится в этом списке, и заявил, что туда включены люди, нарушающие закон. В частности, речь шла о тех, кто имеет ВИЧ-положительный статус и работает в парикмахерской, что якобы противоречит закону.

Фактически это означало передачу данных о состоянии здоровья правоохранительным органам без согласия пациентки. И на суде этот факт даже не пытались скрыть. В ходе разбирательства прокурор, который вел дело, прямо заявил, что сведения о ее ВИЧ-статусе были получены из Центра СПИДа.

С.М.: Как проходил суд? Какой был приговор?

Е.К.: Судебное разбирательство проходило в закрытом режиме, поскольку дело касалось врачебной тайны и конфиденциальности диагноза. Нам очень повезло, что удалось привлечь врачей, которые поддержали нашу сторону и встали на защиту женщины. Она строго следовала режиму приёма АРВ-терапии, благодаря чему у нее была неопределяемая вирусная нагрузка. В суде в качестве эксперта выступил врач, который ясно объяснил, что при таких условиях инфицирование было невозможно. Он также подчеркнул, что на момент разбирательства не было ни одного пострадавшего.

Даже следователь указал в материалах дела, что женщина не пользовалась в работе ножницами или бритвами — только машинкой для стрижки. Она не применяла режущие и колющие предметы, которые могли бы теоретически создать угрозу заражения. Важно отметить, что свидетели, которых вызывали с ее работы, не давали негативных показаний. Они подтверждали, что женщина выполняла свои обязанности профессионально и без нарушений.

В своих прениях я опиралась на эти доказательства, утверждая, что наша подзащитная не могла передать ВИЧ-инфекцию, работая парикмахером. Во время заседания судья задал мне вопрос: «Вы, как общественная защитница, сами бы пошли стричься к этой женщине?» Я объяснила, что для передачи ВИЧ потребовался бы целый ряд маловероятных условий: она должна была бы не принимать терапию, при этом и себя, и меня сильно порезать. Только в таком случае могла бы возникнуть теоретическая угроза заражения. Но даже тогда вероятность передачи была бы крайне низкой.

Отдельно хочу отметить, что махалинский комитет оказал нашей подзащитной серьезную поддержку. Они подали множество ходатайств в ее защиту, несмотря на знание ее ВИЧ-статуса. К этому процессу также подключился комитет женщин, который внес дополнительные ходатайства в пользу нашей клиентки.

Однако женщине все же назначили условный срок — два с половиной года. Это решение было принято из-за существования статьи 113, по которой ее судили. Суд учел, что у нее есть несовершеннолетний ребенок, и это повлияло на смягчение приговора.

До сих пор помню, как судья, оглашая приговор, подчеркнул важность нашего адвокационного направления. Он сказал, что наша организация должна работать над изменением списка запрещенных профессий, потому что он противоречит современному законодательству. Эти слова стали отправной точкой для большого адвокационного процесса, который занял у нас три года. Это дело не просто показало нам необходимость защиты людей в конкретных ситуациях, но и дало старт изменениям на системном уровне.

С.М.: Как сейчас живет эта женщина? Как она себя чувствует?

Е.К.: Представляешь, она проработала в своей любимой профессии более 30 лет. Для нее это было страшным ударом — лишиться работы, на которой она строила всю свою жизнь. Учитывая, что у нее был несовершеннолетний ребенок, а она — мать-одиночка и единственная кормилица в семье, вся ответственность легла на ее плечи. После суда ей было очень тяжело найти подходящую работу. Она бралась за все, что могла: убирала дома, работала гувернанткой, перепробовала массу профессий.

Восстановиться после судебного процесса ей было нелегко. Она проходила длительную психологическую реабилитацию, и мы со своей стороны также оказывали ей поддержку, предоставив услуги психолога. Этот период был очень непростым для нее. Когда наконец изменили законодательство, я первой отправила ей документ с поправками. Но, к сожалению, она так и не вернулась в профессию. Вместо этого она открыла свой маленький бизнес, решив начать жизнь с чистого листа.

Мы продолжали и до сих пор поддерживаем с ней отношения. После суда она приняла участие в Форуме судей, где выступила с открытым лицом и рассказала свою историю. Она поделилась тем, как несправедливая законодательная норма отразилась на ее жизни, и это стало для нее своего рода актом мужества и надеждой на перемены. Её мотивацией было желание помочь другим людям с ВИЧ-положительным статусом, чтобы они больше не сталкивались с теми трудностями и унижениями, через которые прошла она.

Мы понимали, что этот случай касался не только вопросов уголовного права, но и затрагивал социально-экономические права. Он показал, как сильно стигматизация и ограничительные законы могут повлиять на жизнь человека, лишив его источника дохода и возможности работать по профессии. Тем не менее, ее история стала важной частью нашей адвокационной работы и помогла привлечь внимание к необходимости изменений в законодательстве.

С.М.: У нас есть еще одна веха в этой истории — в 2022 году, Узбекистан, третья страна в ЦА (после Таджикистана и Кыргызстана), которая среди прочего получила рекомендацию декриминализировать передачу ВИЧ от комитета ООН CEDAW. Твоя страна получила эту рекомендацию, во многом, благодаря твоему участию и нашему совместному теневому отчету от сообщества. Можем ли мы считать, что полученные рекомендации повлияли на адвокационные процесс в контексте декриминализации ВИЧ, а именно пересмотр списка запрещенных профессий?

Е.К.: У меня было всего три минуты на выступление перед членами Комитета CEDAW, и я прекрасно помню, как мы готовили мое устное заявление. Каждая секунда имела значение. Мне кажется, что все наши усилия были взаимосвязаны, особенно с учетом того, насколько серьезно государство относится к рекомендациям международных структур. В последние годы в стране действительно заметен прогресс в вопросах поддержки женщин.

С 2019 года начали приниматься законы, направленные на обеспечение равноправия мужчин и женщин и борьбу с дискриминацией и насилием в отношении женщин. Я вижу, что в стране делается акцент на экономическую независимость женщин и расширение наших возможностей в образовании и профессиональной деятельности. Особое внимание уделяется доступу женщин к руководящим должностям, что открывает новые перспективы для нас.

Я верю, что заключительные рекомендации Комитета CEDAW могли сыграть свою роль в том, что государство обратило внимание на перечень запрещенных профессий. Этот список давно нуждался в пересмотре, так как он ограничивал права женщин и препятствовал их профессиональному развитию. Работа в этом направлении продолжается, и я надеюсь, что наши усилия помогут еще большему числу женщин избежать подобных ограничений и добиться справедливости.

С.М.: Итак, 2024 год. Случилось то, что, наверное, вы и мы сами не ожидали – приказом министра здравоохранения изменен (сокращен) список запрещенных профессий для людей, живущих с ВИЧ, в Узбекистане. Как это стало возможным?

Е.К.: Согласно новому приказу, ВИЧ-положительные люди теперь могут работать стоматологами, если они не занимаются хирургическими вмешательствами. Этот шаг стал значимым изменением, особенно для нас, поскольку у нас был случай, когда мужчину, работающего зубным техником, привлекли к уголовной ответственности только из-за его ВИЧ-статуса.

В ноябре 2023 года прошел большой феминистский форум, на котором я выступила с речью, вызвавшей широкий отклик. В одной из газет обо мне написали как о лидерке, живущей с ВИЧ. После этой публикации моей историей заинтересовались в администрации президента. Меня пригласили на встречу, чтобы обсудить наиболее острые проблемы, с которыми сталкиваются женщины и люди, живущие с ВИЧ.

На встрече я постаралась использовать этот шанс, чтобы привлечь внимание к списку запрещенных профессий. Я объяснила, что этот законодательный акт не только не приносит общественной пользы, но и разрушает жизни людей, ограничивая их возможности работать по профессии. Мои доводы нашли отклик. У меня сложилось впечатление, что я смогла убедить их в том, что этот приказ давно утратил свою актуальность.

В процессе обсуждения стало очевидно, что чиновники, с которыми я общалась, проявили прогрессивный подход и готовы поддержать инициативу по пересмотру и изменению списка запрещенных профессий. Их готовность к диалогу и понимание важности вопроса вдохновили меня и дали надежду на дальнейшие позитивные изменения.

С.М.: Я правильно понимаю, что у чиновников Минздрава не было сопротивления этой инициативе? До этого врачи передавали милиции данные о людях с ВИЧ. Не могу забыть случай, когда женщину (медсестру) просто посредине рабочего дня вызвали в райотдел, проверяли список ее контактов в телефонной книге, спрашивали с кем она спит, угрожали статьей, и т.д. — такие «профилактические» унизительные методы.

Е.К.: После принятия нового, сокращенного списка запрещенных профессий мы начали проводить тренинги для медицинских работников. В процессе мы столкнулись с определенным сопротивлением — среди участников встречались эпидемиологи, которые не поддерживали изменения. Они утверждали, что риск передачи ВИЧ все равно существует, несмотря на новые данные и международные стандарты. Такие заявления, скорее, демонстрировали их недостаточную осведомленность в вопросе. Позже их коллеги, врачи с большим опытом, даже советовали им воздержаться от таких высказываний, чтобы не вводить в заблуждение других участников.

Особенно важным для нас стало участие главного эпидемиолога Республиканского центра СПИД в этих тренингах. Он представил информацию об изменениях списка профессий максимально профессионально и доступно, что помогло снизить уровень недоверия и сопротивления среди медработников. Его выступления сыграли важную роль в распространении правильных знаний.

Мы также проводили встречи с сотрудниками МВД, в частности с представителями нравственного отдела, который курировал дела, связанные со статьей 113 УК. Именно они ранее инициировали дела против ВИЧ-положительных парикмахеров, приводя к их уголовному преследованию. Эти обсуждения были для нас важны, поскольку позволили донести до сотрудников правоохранительных органов, что старые нормы больше не отвечают современным реалиям и только способствуют стигматизации людей, живущих с ВИЧ.

С.М.: Мы знаем, что ты работала над законопроектом, который уже подан от вашей неправительственной организации «Ишонч ва Хает» в парламент. Вы еще ответ получили, с благодарностью. Как ты оцениваешь перспективу внесения изменений в УК в отношении 113-й статьи?

Е.К.: Я — оптимистка и уверена, что изменения непременно произойдут, это лишь вопрос времени. Уже сейчас видно, что люди, занимающиеся реформами в области законодательства, осознают, что некоторые законы устарели и требуют пересмотра. Приятно видеть, что страна активно нацелена на обновление законодательных систем и приведение их в соответствие с современными реалиями.

Я верю, что наш голос будет услышан. Тем более, что к этим изменениям призывает не только гражданское общество, но и научное и медицинское сообщество, а также международные организации. Это не просто рекомендации, придуманные в узком кругу активисток/в — это глобальная повестка, отражающая прогресс и понимание того, что ВИЧ-инфекция сегодня является хроническим заболеванием, с которым можно жить благодаря доступному и эффективному лечению.

Важно, что в стране уже происходят позитивные сдвиги. Прогрессивные инициативы в области гендерного равенства, защиты прав женщин и людей, живущих с ВИЧ, демонстрируют стремление государства к улучшению качества жизни своих граждан. Эти перемены дают мне уверенность, что реформа затронет и законодательные акты, которые до сих пор ограничивают людей в их правах и свободе выбора профессии.

Я верю в свое государство и его рациональный подход. Вижу, что идет диалог, и он приносит плоды. Мы движемся в сторону перемен, и я убеждена, что они будут положительными для всех.

С.М.: Последний вопрос. Оглядываясь на твой путь от общественной защитницы до экспертки сообщества, которая подает в парламент проект законодательных изменений, расскажи, как ты к такому пришла? Кто/что за этим стоит?

Е.К.: За всеми нашими усилиями всегда стоят люди — люди, которые нуждаются в помощи и поддержке. Я сама женщина, живущая с ВИЧ, и, хотя напрямую не сталкивалась с криминализацией, в моей жизни было немало примеров стигмы и дискриминации. Один из тех, кого я защищала в суде, теперь стал сотрудником нашей организации. И такие истории дают мне силы и вдохновение двигаться дальше.

В глубине души я мечтаю об идеальном мире. Никто не может запретить мне хотя бы пытаться сделать его таким. Моя главная мотивация всегда была в том, чтобы люди, живущие с ВИЧ, больше не сталкивались с дискриминацией и стигмой, чтобы их права уважались и не нарушались только из-за их диагноза.

Я убеждена, что государство должно работать в интересах тех, кто в нем живет. И сегодня у нас действительно есть хорошие перспективы. Мы видим наличие политической воли и гражданского общества, которое активно участвует в продвижении изменений и имеет реальный вес. Это благоприятное время для перемен.

Государство проявляет желание услышать нас и понять наши проблемы. Более того, мы не просто говорим о проблемах, мы помогаем находить решения, и этот процесс становится для меня дополнительной мотивацией. Когда нас слушают и действительно слышат — это вдохновляет. Это значит, что наши усилия имеют значение и ведут к изменениям.

|

Приказ Министра здравоохранения Республики Узбекистан

Об утверждении Перечня видов профессиональной деятельности, запрещенных для лиц, зараженных вирусом иммунодефицита человека

[Зарегистрирован Министерством юстиции Республики Узбекистан 07 мая 2014 года. Регистрационный № 2581] |

Приказ Министра здравоохранения Республики Узбекистан

Об утверждении Перечня видов профессиональной деятельности, запрещенных для лиц, зараженных вирусом иммунодефицита человека

[Зарегистрирован Министерством юстиции Республики Узбекистан 19 февраля 2024 года. Регистрационный № 3497] |

|

Виды профессиональной деятельности, запрещенные лицам, инфицированным вирусом иммунодефицита человека

СПИСОК

1. Профессии, связанные с заготовкой и переработкой крови и ее компонентов.

2. Профессии, связанные с получением крови и ее компонентов, спермы и грудного молока.

3. Профессии, связанные с переливанием крови.

4. Профессии, связанные со следующими медицинскими процедурами: инъекции; диализ; венесекция; катетеризация.

5. Профессии, связанные с косметическими и пластическими операциями.

6. Профессии, связанные со стоматологическими процедурами.

7. Профессии, связанные с родами.

8. Профессии, связанные с абортами и другими гинекологическими операциями.

9. Профессии, связанные с прической и бритьем, пирсингом, маникюром, педикюром и татуировкой. |

Виды профессиональной деятельности, запрещенные лицам, инфицированным вирусом иммунодефицита человека

СПИСОК

1. Профессии, связанные с заготовкой, переработкой и переливанием крови человека и (или) ее компонентов.

2. Профессии, связанные со всеми видами хирургии.

3. Профессии, связанные с родами.

4. Профессии, связанные со следующими медицинскими процедурами: диализ; венесекция; катетеризация. |