Travis Spoor sits in the Kosciusko County Jail, accused, again, of failing to tell his sexual partner that he is HIV-positive.

The 37-year-old is facing malicious mischief charges in three counties for leaving his partners exposed to the disease without their knowledge. He faces up to two and a half years in prison on each charge.

According to court documents, at least two of his sexual partners found out about Spoor’s HIV status through a news article.

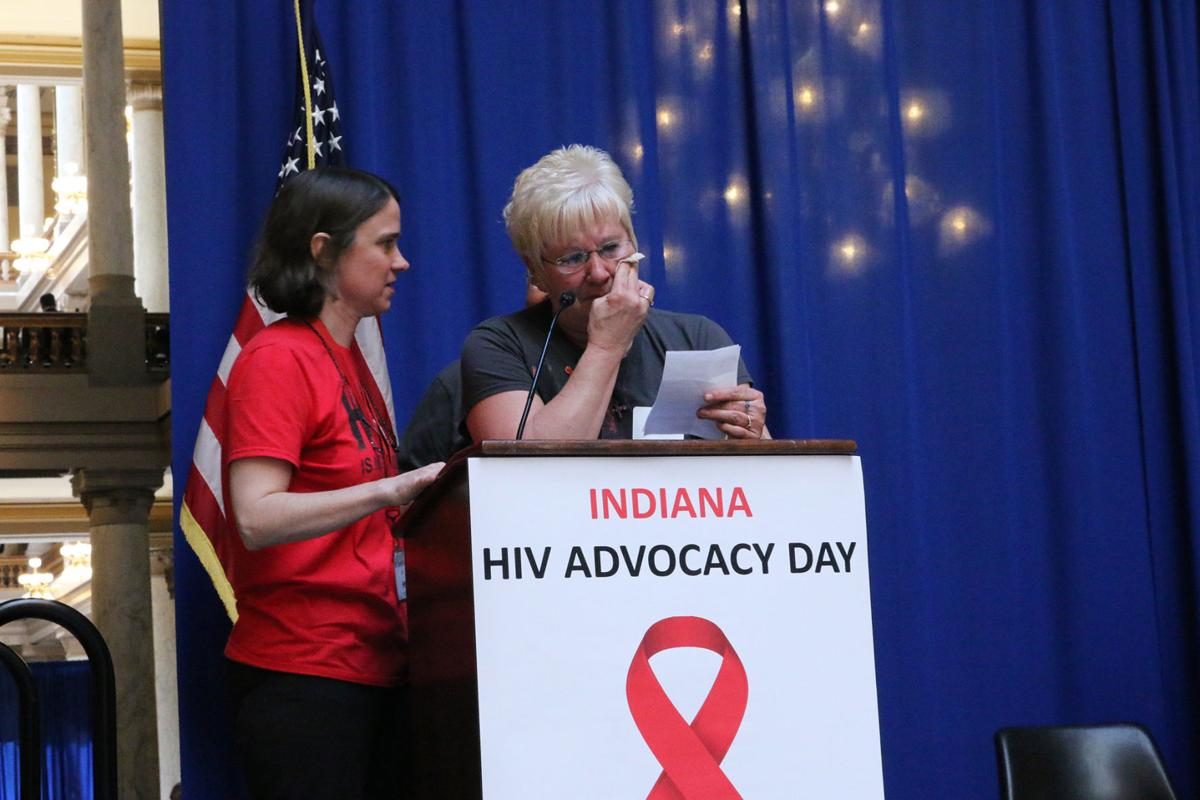

Spoor’s mother, Lisa Holderman, broke down in tears as she said her son isn’t a criminal.

“He’s lost his children. He’s lost his job. He’s lost insurance. He’s lost his home. He’s lost his car,” Holderman told the crowd attending HIV Advocacy Day last month at the Statehouse. “We’re losing everything just to try to get my son out of jail.”

Indiana has several laws that impact the lives of people infected with HIV. In addition to being required to inform sexual partners, they can face penalties for exposing people to any bodily fluid, even those that do not transmit HIV.

Carrie Foote, IUPUI professor and co-chair of HIV Modernization Movement, argues these state laws are outdated and research shows they don’t prevent the spread of the disease. Instead, they can discourage people from getting tested.

In Spoor’s case, Foote doesn’t believe he intended to harm his partners. She compared Spoor’s actions to contraceptive fraud.

“There are things that can cause life changing events in adult sexual decision making that we don’t criminalize in that way,” Foote said.

Foote, along with the HIV Modernization Movement, is working to modernize or repeal a few of the current HIV laws that she argues turns the disease into a crime.

But to describe it as criminalizing is completely inaccurate in the eyes of Terre Haute based Vigo County Prosecutor Rob Roberts.

“It doesn’t do the criminal justice system any service and it certainly doesn’t do HIV people any service to try and scare them to think that they might be prosecuted just for having HIV,” Roberts said.

During his career, Roberts has prosecuted only one HIV case to completion. He said bringing charges against an HIV-positive person for their actions is rare.

Roberts argued the state punishes other behaviors that put people at risk.

“Criminal Recklessness — where you may be reckless in your actions in driving a vehicle or in discharging a firearm and you have put other people at risk in those situations,” Roberts said. “We criminalize those actions because it’s the action that we’re talking about, not the status of someone being behind the wheel of the vehicle or possessing a firearm.”

However, Roberts thinks it’s a possibility that disclosure laws are one of the reasons why people don’t get tested in the first place.

Conquering Stigma

At the Damien Center in Indianapolis, more than 4,000 infected individuals receive care and services from Indiana’s oldest and largest AIDS service organization. For years, Jeremy Turner, director of development and communication at the center, has helped get people tested for HIV.

“Disclosure is the right thing to do, but unfortunately HIV is so heavily stigmatized because of things like duty to warn and because of legislation that might not be fair to them, but also because of the social implications of being HIV positive,” Turner said. “Disclosure is a hard thing to do.”

Stigma is one of the biggest hurdles in ending the HIV epidemic, Turner said, and that’s exactly what the current HIV laws do, according to Foote.

The HIV Modernization Movement’s main goal is to modernize the duty to warn and battery by bodily waste HIV laws. Duty to warn is the law that requires HIV-positive people to reveal their condition to sexual partners and needle-sharing partners. The battery by bodily waste law applies to a range of acts and bodily fluids, including spitting or throwing feces.

For Foote, the main problem with the duty to warn law is that it charges people who have no intention of harming another person. She wants the law revised to require proof that the person had intent to harm.

“The way these laws are worded, if I was sexually assaulted, I would have to disclose to my rapist that I was HIV positive,” Foote said. “There’s nothing in the law that tells that I don’t have to do that.”

The movement is also pushing to repeal the laws that prevent HIV positive people from donating blood or semen altogether. Foote said there’s no risk of transmission if a man with HIV was to seek fertility services. Additionally, the Food and Drug Administration screens blood donations for the disease.

Results of a recent survey of health care providers about HIV disclosure showed that the majority of respondents had little understanding of the law or the consequences. Only 58 percent of the more than 170 respondents said they read the full Indiana duty to warn code and only 43 percent knew the punishment for law breakers.

Those health care providers are the ones to make sure patients sign a form acknowledging that they have a duty to disclose their condition to partners past and present.

John Coberg II, an IUPUI research assistant who worked on the survey along with Foote, said he saw a common theme in the results — that the laws are harmful.

In the survey one anonymous provider wrote, “It often makes the client feel like a criminal, or they’re dirty or wrong when they’re in my office for help. As a care coordination person, you should never want your client to feel any of these things when they walk in your office.”

Changing the laws

When changing a law, Roberts said two questions need to be considered: How is the statute being used, and is it being used in an unfair fashion? In Roberts’ opinion, these laws haven’t been around long enough to answer these questions just yet.

Roberts said it’s the job of the legislature to look at the current laws to see if they need tweaking.

“We can take a look,” Sen. Greg Taylor, D-Indianapolis, said.

Taylor’s focus is the current battery by bodily waste law, since research shows HIV is not transferrable by saliva. He wants to change the law so that HIV positive people aren’t charged differently for having the disease.

“If the chairman of the health committee is willing to go along with it, we can hopefully put some modern legislation in place to protect the public but also not make a criminal out of people because they contracted HIV,” Taylor said

Published in NUVO on May 12, 2017