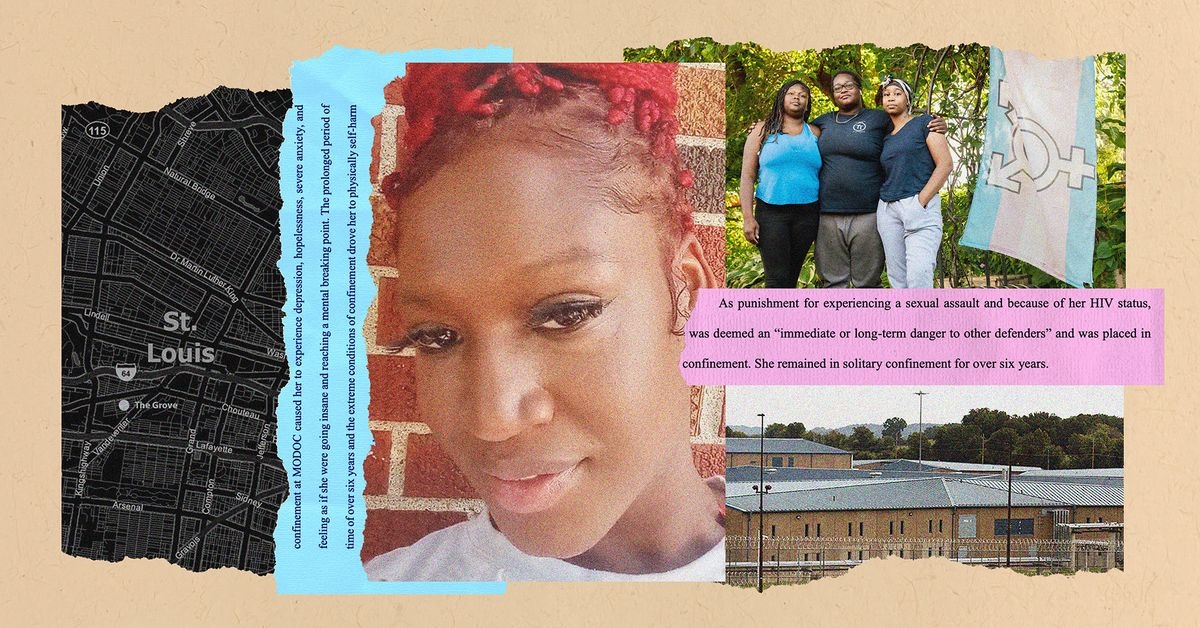

A Woman With HIV Spent Six Years in Solitary. She Sued and Missouri Will Change Its Policy.

Honesty Bishop was attacked by her cellmate. Prison officials deemed her sexually active and kept her in isolation for more than 2,000 days.

Honesty Bishop could hear the screams of other people in solitary confinement. Sometimes it was so cold in her cell, she could see her breath. She dealt with scabies and mold. Her days and nights were spent in extreme isolation.

The Missouri Department of Corrections kept her locked in a cell about the size of a parking space for over six years.

She wrote letters to her sister, Latasha Monroe, in St. Louis. They both wondered why Bishop continued to be held in such severe conditions at Jefferson City Correctional Center, a men’s facility.

Interviews and records on Bishop’s years in solitary confinement paint a dark picture of a person who felt alone and hopeless, and, in the depths of despair, was driven to self-harm.

Bishop, a transgender woman, initially landed there after her cellmate tried to sexually assault her in spring 2015.

She was HIV-positive and because of the assault was classified as “sexually active” — even though she was the victim and had been on medication, making the virus undetectable and therefore untransmissible, according to a federal lawsuit filed against the Missouri Department of Corrections.

Among the reasons people can be kept in isolation, according to the department’s policy, are murder, rape and being sexually active with HIV. In her suit, Bishop said corrections officials kept her in solitary confinement because of her HIV status.

Whenever she appeared before a committee that reviewed her placement in solitary, which generally took place every 30 or 90 days, corrections officials noted 15 times when Bishop had no violations since the previous review.

“I’ve been good,” she told them during a hearing on her solitary confinement in January 2016, and again that September.

Though she filed grievances about how long she had been kept in solitary, her pleas were ignored. Department of Corrections officials wouldn’t release her from the unit until 2021 — after more than 2,000 days.

Missouri is one of three states that singles out people with HIV when it comes to solitary confinement, according to a review of 49 states’ policies on administrative segregation and restrictive housing.

The department’s HIV policy will now be changed under the terms of an Aug. 20 settlement that resulted from the lawsuit.

The state agreed to remove language singling out people with HIV for segregation. The terms also include conducting an assessment of anyone with HIV who is sent to solitary and mandatory training for some prison staff.

The department would not comment specifically on the policy or the lawsuit. Karen Pojmann, a spokeswoman for the agency, said a committee is in the process of overhauling restrictive housing. Two prisons are piloting a new model that includes “meaningful hearings” and programming to help people reenter the general population in prison, she said.

Bishop did not live to see the policy change — she died by suicide on Aug. 13, 2024. She was 34.