Stigma remains a major problem that discourages people from getting tested

Two studies released last month show the tools exist to potentially end the more than three-decades-old scourge of HIV/AIDS, but activists and front-line public health workers in Canada say we simply aren’t using them effectively.

The first study found it’s nearly impossible for an HIV-positive person to transmit the virus if they’re undergoing effective antiretroviral therapy (ART).

The other showed the impressive ability of a drug called Truvada — if taken properly — to protect HIV-negative people who would otherwise be at high risk of contracting the virus.

“I think there’s a real frustration of those of us on the ground, those of us working in public health and epidemiology who know absolutely that the tools are out there and we’re not seeing the support,” says Joshua Edward, a program manager at Vancouver’s Health Initiative for Men(HIM).

High-profile figures in the global fight against HIV/AIDS, including Bill Gates at last month’s World AIDS Conference in Durban, South Africa, have suggested talk of “the end of AIDS” is perhaps premature given its continued spread in much of the developing world, particularly Africa.

Such talk also seems premature in Canada.

Two big problems

Edward says there are two major problems in Canada that deny the promise described in the two studies.

First, there remains a powerful stigma around HIV that discourages people from getting tested.

The second problem is Truvada, approved as a pre-exposure prophylaxis or PrEP, is very expensive, up to $1,000 a month, and isn’t widely available to those who don’t have generous private insurance plans.

The PARTNER study looked at couples where only one partner had HIV but with a viral load suppressed by medication. Out of nearly 60,000 condomless sex acts, not a single HIV transmission occurred.

But HIV infection rates in Canada remain relatively steady, with an estimated 2,500-3,500 new transmissions every year, in part because one in five HIV-positive Canadians don’t even know they have the virus, and so they aren’t receiving the treatment that will keep them healthy and prevent further spread.

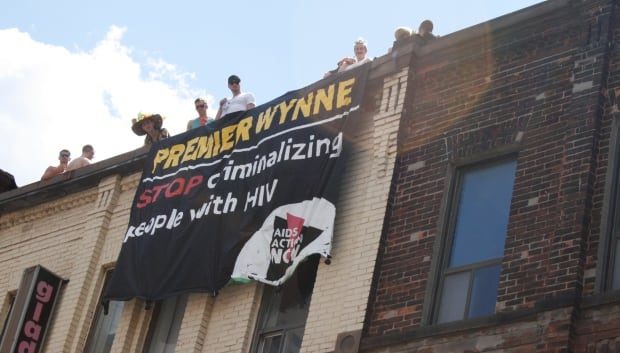

Activists argue stigma is a big reason why so many Canadians don’t get tested, and it’s fuelled by the fact that our laws criminalize the non-disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status, even if no transmission occurs and despite the latest evidence that shows viral suppression makes it virtually impossible to transmit the virus.

Stigma encourages spread

Sandra Ka Hon Chu, director of research and advocacy with the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network (CHALN), says criminal sanctions of HIV-positive people encourage the spread of the virus.

“People who might not know their status won’t get tested because you would have the knowledge of your HIV status, which is a requirement of a conviction,” she says. “That then deters open discussions with health-care providers and creates a lot of stigma that prevents people from getting on ART.”

More than 180 people to date in Canada have been charged for not disclosing their HIV status, according to CHALN. In most cases, they were charged with aggravated sexual assault, which carries a maximum life sentence and a possible sex offender designation.

In 2011, for example, an HIV-positive woman north of Toronto had oral sex with a man and unprotected vaginal sex with two others. She didn’t disclose her HIV status and was charged with three counts of aggravated sexual assault.

Though she was acquitted for the oral sex based on the unlikelihood of transmission, the trial judge convicted her for one of the counts related to vaginal sex — even though she was taking her medication, had an undetectable viral load and no transmission occurred — because the victim was “exposed to a significant risk of the transmission of HIV and that risk endangered his life.”

Law is a ‘blunt instrument’

Chu says the law needs to be updated given the recent scientific evidence that shows even condomless vaginal sex with an HIV-positive-but-undetectable partner carries very low risk of transmission.

Criminal law, she says, is too much of a “blunt instrument” to regulate a moral problem with so many grey areas. She says most people fail to disclose their status because they fear rejection, physical violence, or, for example, because they fear the disclosure may be used against them later.

“A woman who might be living in an abusive relationship who is positive might decide to go to the police to charge their partner with violence and that partner might threaten to say they didn’t disclose their HIV status to them,” Chu says.

She sees many possible solutions.

The provinces enforce the Criminal Code, so they have the power to rewrite prosecutorial guidelines on what should and should not be pursued by the Crown.

The federal government could also change the Criminal Code to match international guidelines put forward by UNAIDS, the Global Commission on HIV and the Law and others. This would include limiting criminalization to cases where a person knows their HIV-positive status, acts with the intention to transmit HIV, and does in fact infect the negative partner with the virus.

More education and testing

Edward says Canada also needs to invest more in HIV education and testing outside of the major cities, where the stigma is greatest and HIV rates are often higher, including in some First Nations communities.

“If you live outside of a metro area, those barriers can be significant.”

He also says Canada needs a national HIV strategy that includes investing in PrEP for HIV-negative people who are at higher risk of contracting the virus.

- Advocates for HIV prevention pill push for better access, information

- HIV prevention pill could save health care dollars

“We need broader access,” he says. “We need insurance companies to be more generous in their support. You have to have a really high degree of privilege to be able to access it,” he says.

“You have to know how the medical system works. Mine is covered by insurance. It took probably a good two, three weeks of back and forth with my insurance company to access it, including being able to advocate for myself, able to speak from my perspective with righteous indignation.”

Delays

Health Canada expedited the process for approving Truvada as PrEP. It signed off in February, months before many expected, and emphasized Truvada should be used along with condoms.

But Quebec is the only province to publicly fund the drug, while the rest wait for the results of the Common Drug Review (CDR), which is expected to be complete in the fall. From there, the provinces will make their own decisions on whether to cover it, which could take months.

Michael Fanous, a Toronto-based pharmacist who specializes in HIV medications, thinks there should be an expedited process to get the drug listed for provincial drug plans.

“We’ve run into this problem for 30 years in treatment as new HIV drugs take much longer to get approved in Canada and then even longer to get covered.”

Edward’s organization in Vancouver, HIM, isn’t waiting around for government action. Instead, it launched getpreped.ca to get more people educated about PrEP.

“It gets back to almost every day in this province, someone is going to receive an HIV diagnosis … and at least for some of them, PrEP could have prevented that diagnosis,” he says.

“If you want to talk criminality, that’s criminal to me.”