I owe my life to you, says judge

“The fact that I am here today at all is a tribute to the activists, researchers, doctors and scientists in the audience,” Judge Edwin Cameron told delegates to the Durban Aids conference, delivering the Jonathan Mann memorial address. He asked sex workers and transgender people to join him on stage. His godson Andy Morobi also addressed the conference.

It is a great privilege and an honour to be here. At the start of a very busy conference, with many stresses and demands and anguishes, I want to start by asking us to pause quietly for just a few moments.

It has been 35 years since the Western world was alerted to Aids. The first cases of a baffling, new, terrifying, unknown syndrome were first reported in the northern summer of 1981. The reports were carried in the morbidity and mortality weekly reports of the CDC on 5 June 1981.1

These last 35 years, since then, have been long. For many of us, it has been an arduous and often dismaying journey.

Since this first report, 35 million people have died of Aids illnesses2 – in 2015 alone, 1.1 million people. 3

We have felt the burden of this terrible disease in our bodies, on our minds, on our friends and colleagues, on our loved ones and our communities.

Aids exposes us in all our terrible human vulnerability. It brings to the fore our fears and prejudices. It takes its toll on our bodily organs and our muscles and our flesh. It has exacted its terrible toll on our young people and parents and brothers and sisters and neighbours.

So let us pause, first, in remembrance of those who have died –

- those for whom treatment didn’t come in time

- those for whom treatment wasn’t available, or accessible

- those denied treatment by our own failings as planners and thinkers and doers and leaders

- those whom the internal nightmare of shame and stigma put beyond reach of intervention and help.

- These years have demanded of us a long and anguished and grief-stricken journey.

- But it has also been a journey of light – a journey of technological, scientific, organisational and activist triumph.

So we must pause, second, to celebrate the triumphs of medicine, science, activism, health care professional dedication and infrastructure that have brought ARVs to so many millions.

Indeed, the fact that I am here today at all is a tribute to the activists, researchers, doctors and scientists in the audience.

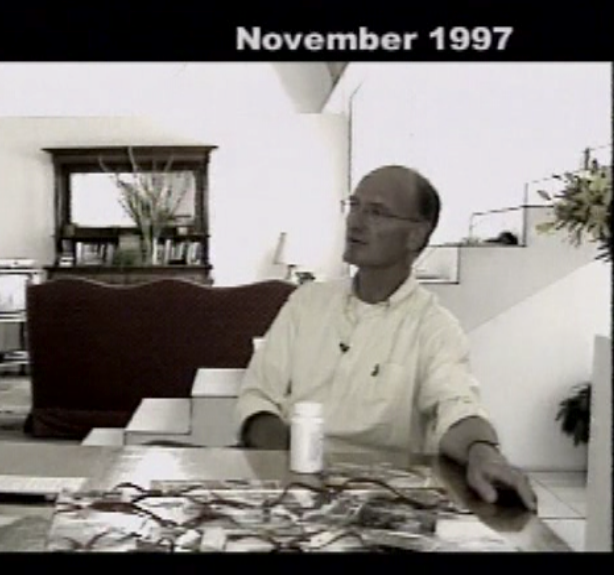

Many of you were responsible for the breakthroughs that led to the combination anti-retroviral treatment that I was privileged to start in 1997 – and which has kept me alive for the last 19 years.

I claim no credit and seek no praise for surviving. It felt like an unavoidable task.

All of us here today who are taking ARVs – let us raise our hearts and humble our heads in acknowledgement of our privilege – and often plain luck – in getting treatment on time. That treatment has given us life.

So let us pause, third, to honour the doctors – the scientists – the researchers – the wise physicians and strong counsellors who have saved lives and healed populations in this epidemic.

As important, fourth, let us pause to honour the activists, whose work made treatment available to those who would not otherwise have received it.

We pause to honour the part, in treatment availability and accessibility, of angry, principled and determined activists, in South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign and elsewhere. For millions of poor people, their anger brought the gift of life.

Without their courage, strategic skill and passion, medication would have remained unimaginably expensive, out of reach to most people with HIV. They led a successful campaign that saved millions of lives.

The fact that many millions of people across the world are, like me, receiving ARV treatment, is a credit to their work.

They taught us an important lesson. Solidarity and support are not enough. Knowledge and insight are not enough. To save lives, we need more. We need action – enraged, committed, principled, strategically ingenious action.

They refused to acquiesce in a howling moral outrage. This was the notion that life-saving treatment – treatment that was available, and that could be cheaply manufactured – would not given to poor people, most of them black, because of laws protecting intellectual property and patent-holders’ profits.

The Treatment Action Campaign and their world-wide allies frontally tackled this. They changed the way we think about healthcare and essential medicines access.

What is more, without the Treatment Action Campaign, President Mbeki’s nightmare flirtation with Aids denialism between 1999 and 2004 would never have been defeated.

Instead, the TAC took to the streets in protest. They demanded treatment for all. And when President Mbeki proved obdurate, they took to the courts.

Because of my country’s beautiful Constitution, they won an important victory. Government was ordered to start making ARV treatment publicly available.

Today my country has the world’s largest publicly provided anti-retroviral treatment program.4 More than 3.1 million people, like me, are receiving ARVs from the public sector.5

I am particularly proud that when someone with HIV registers for treatment in South Africa, they should not be asked to show an identity document or a passport or citizenship papers. That is as it should be. The imperatives and ethics of public health know no artificial boundaries.

In the sad history of this epidemic, the triumphs of Aids activists, on five continents, are a light-point of joy.

So there is much to celebrate. I celebrate the joy of life every day with the medication – which keeps a deadly virus effectively suppressed in my arteries and veins, enabling me to live a life of vigour and action and joy.

But we must not forget that Aids continues to inflict a staggering cost on this continent and on our world.

What is more important than my survival, and that of many millions of people in Africa and elsewhere on successful ARV treatment, is those who are not yet receiving it.

There still remains so much that should be done. More importantly, there still remains so much that can be done.

Too many people are still denied access to ARVs. In South Africa, despite our many successes, well over six million people are living with HIV. And, though about half of South Africans with HIV are still not on ARVs,6 from September this year ARVs will be provided to all with HIV, regardless of CD4 count.

Globally, of the 36.7 million people living with HIV at the end of 2015, fewer than half had access to ARVs.7

Worse, the pattern of ARV availability is one that reflects our own weaknesses and vices as humans – our prejudices and hatreds and fears, our selfish claiming for ourselves what we do not grant to others.

Most of those still in need of ARVs are poor, marginalised and stigmatised – stigmatised by poverty, sexual orientation, gender identity, by the work they do, by their drug-taking and by being in prison.

Dr Jonathan Mann, to whom this lecture is dedicated, did pioneer work in recognising the links between health and human rights. He stressed that to address Aids, “we must confront those particular forms of inequity and injustice – unfairness, discrimination – not in the abstract, but in its specific and concrete manifestations which fuel the spread of Aids.”8

He recognised that the perils of HIV are enormously increased by laws that specifically criminalise transmission of HIV and exposure of another to it. This was also confirmed by the wonderful and authoritative work the Global Commission on HIV and the Law has recently done.

These laws are vicious, ill-considered, often over-broad and intolerably vague. By criminalising undefined “exposure”,9 they ignore the science of Aids, which shows how difficult HIV is to transmit.10 Apart from driving those at risk of HIV away from testing and treatment, they enormously increase the stigma that surrounds HIV and Aids.

Across this beautiful continent of Africa, men who have sex with men (MSMs) remain chronically under-served. They lack programs in awareness, education, outreach, condom provision and access to ARVs. As a recent study by Professor Chris Beyrer and others has shown, we have the means to end HIV infections and Aids deaths amongst men having sex with men. Yet “the world is still failing”.11

For this, there is one reason only – ignorance, prejudice, hatred and fear. Theworld has not yet accepted diversity in gender identity and sexual orientation asa natural and joyful fact of being human.

Seventy eight countries in the world continue to criminalise same-sex sexual conduct. Thirty four of them are on this wide and wonderful continent of Africa.

It is a shameful state of affairs. As a proudly gay man I have experienced the sting of ostracism, of ignorance and hatred. But I have also experienced the power of redeeming love and acceptance and inclusiveness.

We do not ask for tolerance, or even acceptance. We claim what is rightfully ours. That is our right to be ourselves, in dignity and equality with other humans.

Discrimination on the ground of sexual orientation or gender identity is a colossal and grievous waste of time and social energy.

As our beautiful Archbishop Desmond Tutu has said, when we face so many devastating problems – poverty, drought, disease, corruption, malgovernance, war and conflict – it is absurd that we waste so much time and energy on sexual orientation (“what I do in bed with whom”.)12

The sooner we accept the natural fact that gender and orientation diversity exists naturally between us, the quicker we can join together our powers of humanity to create better societies together.

The same applies to sex workers. Sex workers are perhaps the most reviled group in human history – indispensable to a portion of mostly heterosexual males in any society, but despised, marginalised, persecuted, beaten up and imprisoned.

Sex workers work.13 Their work is work with dignity.

Why do people do sex work? Well, ask a sex worker –

- To buy groceries, and pay their rent, to study, to send their children to school, and to send money to their parents and extended family.

- It is hard work. Perilous work. Sex workers have a tough, dangerous job. They deserve our love and respect and support – not our contempt and condemnation.

They deserve police protection, not exploitation and assault and humiliation.

More importantly, they deserve access to every bit of HIV knowledge and power that can protect them from infection and can help them to protect others from infection. 14

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) works for sex workers.15 It should be made available to them, as a matter of urgent priority, as part of all national Aids treatment programs.

In September 2015, the World Health Organization, recognizing PrEP’s efficacy, recommended that PreP be provided to all “people at a substantial risk of HIV,” including sex workers. 16

When we in South Africa launched our three-year National Sex Worker HIV Plan in March 2016, we proposed providing PrEP to sex workers. WHO recognized South Africa as the “first country in Africa to translate this recommendation into national policy.”17

Beginning last month (June 2016), the first programs began providing daily PrEP to sex workers in South Africa.18

Criminalising sex workers is a profound evil and a distraction from the important work of building a humane society.19

Especially vulnerable too are injecting drug users. Upon them are visited the vicious consequences of perhaps the most colossal public policy mistake of the last 80 years – the war on drugs.

The vulnerability of injecting drug users is evident in the high percentage of injecting drug users with HIV. Throughout the world, of about 13 million injecting drug users, 1.7 million (13%) are living with HIV. 20

They are denied elementary life-saving services. This is not on the supposedly “dark” continent of Africa – but in the United States of America. If you want an example of evidence-ignoring public policy, that causes loss of life and injury, and spread of HIV, do not look complacently to President Mbeki’s South Africa twelve years ago – look to the United States of America, now, and the federal government’s refusal to make needle substitution available to IDUs . While the US government’s decision to partially lift this ban on federal funding for needle exchange programs earlier this year is a welcome development, this decision was only spurred by an outbreak of new HIV cases among drug users in the United States, 21 and the delay has undoubtedly resulted in preventable HIV infections. 22

Injecting drug users living with HIV are further denied access to treatment. And the United States and Canada, healthcare providers are less likely to prescribe ARVs for injecting drug users, because they assume that IDUs are less likely to adhere to treatment and/or will not respond to it. This is in spite of research showing similar responses and survival rates for those who do have access to ARVs. 23

We know exactly what we have to do to tame this epidemic.

We have to empower young people and especially young girls, to make health seeking choices when thinking about sex and when engaging in it. 24

We have to redouble our prevention and education efforts.

Prevention remains a key necessity in all our strategies about Aids.

Second, we have to test, test, test, test, test, test and test. We cannot promote consensual testing enough. Testing is the gateway to knowledge, power, understanding and action.

Without testing there can be no access to treatment. The more we test, the more we know and the more we can do.

Testing must always be with the consent of the person tested. But we have to be careful that we do not impose unnecessarily burdensome requirements for HIV testing.

HIV is now a fully medically manageable disease. Consent to testing should be capable of being implied and inferred. We must remove barriers to self-testing.

I speak of this with passion – because, by making it more difficult for health care workers to test, we increase the stigma and the fear surrounding HIV.

We must make it easier to test, not harder. Gone are the terrible days when testing was a gateway only to discrimination, loss of benefits and ostracism.

In all this, we must be attentive to the big understated, underexplored, under-researched issue in the epidemic. That is the effect of the internalisation of stigma within the minds of those who have HIV and who are at risk of it.

Internalised stigma has its source in outside ignorance, hatred, prejudice and fear.

But these very qualities are imported into the mind of many of us with HIV and at risk of it.

Located deeply within the self, self-blame, self-stigma and self-paralysing fear are all too often deadly. 25

We must recognise internalised stigma. I experienced its frightening, deadening effects in my own life. Millions still experience it. We must talk about it. And we must find practical ways to reduce its colossally harmful effects.

And, most of all, we must fix our societies. As my friend and comrade, Mark Heywood, has recently written, we have medically tamed Aids. But we have not tamed the social and political determinants of HIV, particularly the overlapping inequalities on which it thrives – gender, education, access to health care, access to justice. That is why prevention strategies are not succeeding.

A better response to HIV, Mark rightly says, needs a better world. Governments must deliver on their human rights obligations. Activists and scientists must join struggles for meaningful democracy, gender equality and social justice. Activists must insist on equal quality education, health and social services; investment in girls and plans backed by money to stem chronic hunger and malnutrition.26

But, to end, I want to return to the light points in our struggle against the effects of this disease over the last 30 years.

I want to end with a thrilling fact – this is that, unexpectedly, joyously, beyond our wildest dreams, perinatal and paediatric ARVs have proved spectacularly and brilliantly successful.

First, let us rejoice that perinatal transmission of HIV can be completely eliminated. It was about this that the Treatment Action Campaign fought President Mbeki’s government all the way to the Constitutional Court, the Court in which I am now privileged to sit.

Now we know how effectively we can protect babies at birth and before birth from infection with HIV.

In South Africa, the rate of mother-to-child transmission of HIV is now reduced to 4%.27 Worldwide, in 2015, 77% of all pregnant women received treatment to prevent perinatal transmission of HIV.28

Last year, Cuba became the first country to eliminate mother to child transmission of HIV entirely. 29 In 2016, Thailand, Belarus, and Armenia have also reached this milestone. 30

More even, fifteen years ago we didn’t know how well babies and toddlers would tolerate ARVs.

We didn’t know just a decade ago how young children born with HIV would thrive on ARVs.

And would they take their ARVS? Would they grow to normalcy?

Instead of this uncertainty, we now know, triumphantly, that ARVs work wonderfully for children born with HIV.

I want to rejoice in the beauty and vigour of my godson Andy Morobi. Andy and I became family twelve years ago, at the end of 2004.

He is young, energetic, ambitious and enormously talented. He was born with HIV. He has been on ARVs for the last eight years. Like me, he owes his life to the medical and social miracle of anti-retroviral treatment.

I want to end on another light point. I want to honour the treatment activists from Africa, Europe, North America, South America, Australasia and Asia, who fought for justice in this epidemic.

I want to honour them, like Dr Jonathan Mann, to whom this lecture is dedicated. Like my mentor, Justice Michael Kirby of Australia, for their energy and courage and determination and sheer resourceful and resilience in fighting for justice in this epidemic.31

And I want to end by celebrating the fact that we have sex workers here this morning. They are wearing the T-shirts in the slide a few minutes ago. The T-shirts say: “THIS IS WHAT A SEX WORKER LOOKS LIKE”.

And, most of all, as a gay white man who has lived a life privileged by my race and my profession and my maleness, I ask that we celebrate the astonishing courage of transgender activists, of lesbians and gay men across the continent of Africa and in the Caribbean.

They are claiming their true selves. They do so often at the daily risk of violence, attack, arrest and imprisonment.

They have the right to be their beautiful selves. They are claiming a right to be full citizens of Africa, the Islands and the world. They have done so at extraordinary risk.

They know that they cannot live otherwise.

It is to these brave people that this conference should be dedicated: to the sex workers, injecting drug users, migrants, lesbian, gays and transgendered people, the children, the activists, those in prison, the poor and the vulnerable.

It lies within our means to do everything that will ensure whole lives and whole bodies for everyone with HIV and at risk of it.

All it requires is a passion and a commitment and a courage starting within ourselves. Starting within each of ourselves. Starting now.

Thank you very much.

For footnotes please see original articles in GroundUp