Overview

Zimbabwe was the first African country to enact an HIV-specific criminal law, including it in the Sexual Offences Act 2001. However, more than two decades later, Zimbabwe become only the second country in Africa to fully repeal its HIV-specific criminal law.

The 2001 law, which was supported by women’s rights groups who sought to address violence against women, criminalised anyone diagnosed HIV-positive who “intentionally does anything or permits the doing of anything” which (s)he “knows (…) will infect another person with HIV”.

This law was amended in 2006 through the enactment of the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act 2006. The new Act included two HIV-specific provisions. The first was section 79, erroneously titled ‘deliberate transmission of HIV’. Despite its title, section 79 did not require HIV transmission or for an accused to have an intention to transmit HIV: only that they undertook an act that included “a real risk or possibility” of transmitting HIV. Further, section 79 could be applied to anyone who knew they had HIV or who realised “there is a real risk or possibility” they might have HIV. The broad terms of the law meant that it was applicable in a wide range of circumstances including when HIV was not diagnosed, when HIV transmission was not intended or deliberate, or where HIV was not even transmitted. The law did provide for a defence if the HIV-negative partner knew the accused had HIV, and consented to the act while appreciating the nature of HIV and the possibility of transmission.

In July 2019, Zimbabwe’s government moved to repeal section 79 of the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act through the newly gazetted Marriages Bill. The move followed public statements by the Justice, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs Minister that global thinking suggested such laws stigmatised people living with HIV and AIDS. The second reading of the Bill in February 2020 attracted support from female parliamentarians, and in June 2020 it was reported that the Bill had passed its third reading in the House of Assembly and would move to the Senate. Despite these positive steps, in January 2021 section 79 was one of a number of laws for which the fines available for an offence were doubled. In April 2021, progress on the Bill continued after being stalled for nearly a year due to reservations by traditional leaders (unrelated to HIV provisions), and it was reported to be under consideration in the Senate. In November 2021 it was reported that the Bill was finalised, but it was not until March 2022 that the Bill was finally adopted, having passed all stages in Parliament. The passage of the Bill mean that section 79 was repealed, making Zimbabwe only the second African country to fully repeal its HIV-specific criminal law.

Section 78 of the Act, which broadly criminalised the ‘deliberate infection of another with a sexually transmitted disease’, but made an explicit exception of HIV, remained in place. The penalty under section 78 was lower than section 79 at five years’ imprisonment and/or a fine. In April 2024, it was reported that the government was seeking to amend section 78 so as to remove the exception of HIV and include it as a prosecutable disease alongside other STIs. This proposal – included in a bill titled the Criminal Laws Amendment (Protection of Children and Young Persons) Bill – would have reversed the decriminalisation of HIV. Following domestic and international criticism, in June 2024 the government dropped this proposal from the Bill, stating that HIV transmission should only be criminalised where it is an aggravating factor in sexual assault against young people. The final version of the bill, passed in September 2024, repealed section 78 completely and replaced it with a new offence: “deliberate infection of a child with a sexually transmitted disease”, which, unfortunately, included HIV amongst the list of STIs. Local advocates are especially concerned with the possibility of this new criminal law being used to prosecute women living with HIV who breastfeed or comfort nurse.

The second section adopted through the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act relevant to HIV criminalisation was section 80, which provides for increased penalties if a person convicted of a sexual offence is found to be HIV-positive, whether or not the accused knew they had HIV at the time of the offence. Despite the repeal of section 79 and section 78, section 80 remains in place.

During the drawn out repeal process of section 79, which took almost three years, prosecutions continued, with the most recent reported in December 2021.

It is understood that there were many attempts at prosecution before the first successful prosecution in 2008. The case involved a 26-year-old woman who pled guilty to not disclosing her HIV-positive status before having condomless sex with a male partner. She received a five-year suspended sentence, primarily because her partner did not test HIV-positive. The partner actually tried to get the charges withdrawn and attempted to undermine the case by not attending court.

As of April 2021, there had been at least 18 HIV criminalisation cases, giving Zimbabwe the highest known rate of HIV prosecutions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Over time, it had become apparent that Zimbabwe’s HIV-specific criminal laws do not protect women. Numerous cases have involved alleged sexual transmission of HIV, with many of the accused being women (e.g. 2010, 2012, 2018), including in cases where it is likely the woman was infected by her accuser spouse (although she was diagnosed first) and where men have made allegations as revenge for complaints about domestic violence. In another case, a man was fined US$9 for falsely accusing his girlfriend, who subsequently tested HIV-negative, of infecting him with HIV.

In October 2020, a young HIV-positive woman was charged with ‘deliberate transmission’ after allegedly breastfeeding her friend’s baby to stop it crying. There is no evidence to date to suggest that HIV was transmitted. The outcome of this case is not yet known.

In April 2021 a woman was released on bail after being accused by her lover of deliberately infecting him with HIV. It is said that the two had sex with protection on several occasions and neither knew their HIV status. At a later point they went for a test and the woman tested positive while the man tested negative. There is no evidence to suggest that HIV had been transmitted and it was also revealed that the man had wilfully removed a condom his lover put on during sex on the day he alleges to have been infected. Nevertheless, the woman was charged with deliberate transmission of HIV and trial was set for May 2021, though the outcome of the case is not known.

During the lifetime of section 79 there were a number of cases of accused – usually men – who had been acquitted or had their sentences greatly reduced by a higher court. For example, a 2019 appeal saw a man succeed in having his ten year sentence reduced to two years following his conviction for having condomless sex, as HIV was not transmitted. The man was taking treatment, although it is unclear whether transmission risk was considered.

Following the repeal of section 79, it was reported that the Chair of the Parliamentary Committee on Health and Child Care, Dr Ruth Labode, suggested that all those serving prison sentences for ‘deliberate transmission of HIV’ should be given amnesty and released from prison.

In February 2023, a constitutional challenge was brought by a woman who was arrested in March 2022, and placed on remand in April, for alleged HIV transmission under section 79. The application argued that the charges must be dropped as the corresponding offence no longer exists. In April 2023, the High Court issued a ruling which stopped the prosecution of the woman while a review of the decision to prosecute was pending.

Laws

Criminal Laws Amendment (Protection of Children and Young Persons) Act, 2024.

“70A Deliberate infection of child with a sexually transmitted

disease

(1) In this section—

“sexually-transmitted disease” includes syphilis, gonorrhoea,

herpes, HIV and all other forms of sexually-transmitted

diseases.

(2) Any person who—

(a) knowing that he or she is suffering from a sexually-transmitted

disease; or

(b) realising that there is a real risk or possibility that he or she

is suffering from a sexually-transmitted disease;

intentionally infects any child with the disease, or does anything or causes

or permits anything to be done with the intention or realising that there

is a real risk or possibility of infecting the child with the disease, shall

be guilty of deliberately infecting that child with a sexually-transmitted

disease and liable to a fine up to or not exceeding level fourteen or im-

prisonment for a period not exceeding five years or both.

(3) If it is proved in a prosecution that the person charged was suf-

fering from a sexually-transmitted disease at the time of the crime, it shall

be presumed, unless the contrary is proved, that he or she knew or realised

that there was a real risk or possibility that he or she was suffering from it.

(4) It shall not be a defence to a charge under subsection (1) for

the accused to prove that the child concerned—

(a) knew that the accused was suffering from a sexually-

transmitted disease; and

(b) consented to the act in question, appreciating the nature

of the sexually-transmitted disease and the possibility of

becoming infected with it.

(5) A court convicting a person for any crime constituting un-

lawful sexual conduct against a child shall, if it also convicts that person

for deliberately infecting that child with a sexually-transmitted disease,

not make any part of the sentence of imprisonment imposed for the latter

crime run concurrently with any sentence of imprisonment imposed for

the first-mentioned crime.”.

Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act

Section 79. Deliberate transmission of HIV [repealed following passage of the Marriages Bill]

(1) Any person who

(a) knowing that he or she is infected with HIV; or

(b) realising that there is a real risk or possibility that he or she is infected with HIV;

intentionally does anything or permits the doing of anything which he or she knows will infect, or does anything which he or she realises involves a real risk or possibility of infecting another person with HIV, shall be guilty of deliberate transmission of HIV, whether or not he or she is married to that other person, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a period not exceeding twenty years.

(2) It shall be a defence to a charge under subsection (1) for the accused to prove that the other person concerned—

(a) knew that the accused was infected with HIV; and

(b) consented to the act in question, appreciating the nature of HIV and the possibility of becoming infected with it.

Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act

Section 80. Sentence for certain crimes where accused is infected with HIV

(1) Where a person is convicted of—

(a) rape; or

(b) aggravated indecent assault; or

(c) sexual intercourse or performing an indecent act with a young person, involving any penetration of any part of his or her or another person’s body that incurs a risk of transmission of HIV;

and it is proved that, at the time of the commission of the crime, the convicted person was infected with HIV, whether or not he or she was aware of his or her infection, he or she shall be sentenced to imprisonment for a period of not less than ten years.

(2) For the purposes of this section—

(a) the presence in a person’s body of HIV antibodies or antigens, detected through an appropriate test, shall be prima facie proof that the person concerned is infected with HIV;

(b) if it is proved that a person was infected with HIV within thirty days after committing a crime referred to in those sections, it shall be presumed, unless the contrary is shown, that he or she was infected with HIV when he or she committed the crime.

Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act

Section 78. Deliberate infection of another with a sexually transmitted disease

(1) In this section “sexually-transmitted disease” includes syphilis, gonorrhea, herpes, and all other forms of sexually-transmitted diseases except, for the purposes of this section, HIV.

(2) Any person who

(a) knowing that he or she is suffering from a sexually-transmitted disease; or

(b) realising that there is a real risk or possibility that he or she is suffering from a sexually-transmitted disease;

intentionally infects any other person with the disease, or does anything or causes or permits anything to be done with the intention or realising that there is a real risk or possibility of infecting any other person with the disease, shall be guilty of deliberately infecting that other person with a sexually-transmitted disease and liable to a fine up to or exceeding level fourteen or imprisonment for a period not exceeding five years or both.

(3) If it is proved in a prosecution for spreading a sexually-transmitted disease that the person charged was suffering from a sexually-transmitted disease at the time of the crime, it shall be presumed, unless the contrary is proved, that he or she knew or realised that there was a real risk or possibility that he or she was suffering from it.

(4) It shall be a defence to a charge under subsection (1) for the accused to prove that the other person con- cerned—

(a) knew that the accused was suffering from a sexually-transmitted disease; and

(b) consented to the act in question, appreciating the nature of the sexually-transmitted disease and the possibility of becoming infected with it.

Further resources

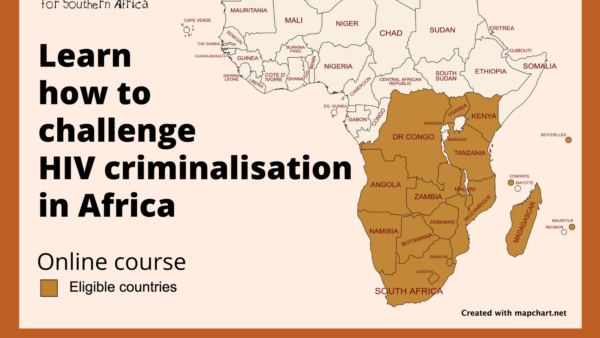

Identifies and examines legal and human rights issues affecting in particular people living with HIV, people with tuberculosis (TB) and those at higher risk of HIV exposure, such as key and affected populations – women, young people,

gay men and other men who have sex with men, sex workers, prisoners, persons with disabilities and people who inject drugs. The LEA makes recommendations to respond to these issues.

The two questions which are sought to be answered relate to the constitutional validity of section 79 of the Criminal Code. These heads of argnment will be confined therefore to whether the provision is too wide, arbitrary and therefore violative of the protection of the law guarantees. It is submitted that the legislature has created an offence which is as scary as the evil that it seeks to redress.

In this June 2016 ruling, the Court unanimously finds against the two applicants and re-states that the only defence to prosecution is disclosure of known or potential HIV infection (which, it says, trumps any right to privacy) and suggests people with HIV can be discriminated against by the law if the reason is to protect public health.

The article finds that, if applied by lawyers, prosecutors and courts, the Expert consensus statement on the science of HIV in the context of criminal law may alleviate some unjust prosecutions and convictions in guiding courts to assess evidence on HIV transmission, to draw appropriate inferences on mental elements of the offence, to recognise defences on the basis of transmission risk-reducing conduct, and to more appropriately inform the courts’ assessment of the harm of HIV infection in sentencing. The implications of the science reflected in the Expert Consensus Statement may also weigh in favour of a finding by the courts that the offence is unconstitutional if a new constitutional case is made against the offence.

HIV Justice Network's Positive Destinations

Visit the Zimbabwe page on Positive Destinations for information on regulations that restrict entry, stay, and residency based on HIV-positive status, as well as access to HIV treatment for non-nationals.