The HIV Justice Network published new data this week showing a troubling rise in the number of people criminalised for HIV non-disclosure, potential or perceived exposure, or unintentional transmission in 2024 and the first half of 2025. As legal reforms appear to be stalling, discriminatory prosecutions, harsh sentences, and misuse of outdated laws continue to impact people with HIV and the HIV response.

The figures, presented at the 13h IAS Conference on HIV Science (IAS 2025) in Kigali, Rwanda, are drawn from the Global HIV Criminalisation Database. The database documents criminal cases and legal developments involving HIV-specific or general criminal laws worldwide.

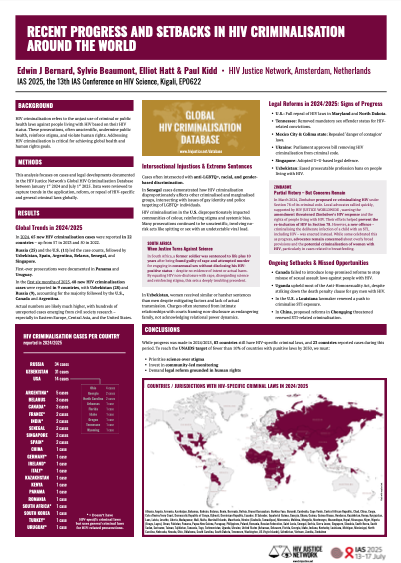

In 2024, at least 65 HIV criminalisation cases were reported across 22 countries – up from 57 in 2023 and 50 in 2022. Russia (25 cases) and the United States (11) led the global tally, followed by Uzbekistan, Spain, Argentina, Belarus, Senegal, and Singapore. For the first time, prosecutions were documented in Panama and Uruguay.

The upward trend continued into 2025, with 48 cases reported in just the first six months. Uzbekistan (28) and Russia (9) again accounted for the majority, alongside new cases in the U.S., Canada, and Argentina. However, the actual number of cases is likely much higher, particularly in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and the United States, where civil society organisations report many cases go undocumented.

“These cases show that HIV criminalisation remains a global crisis,” said Edwin J. Bernard, Executive Director of the HIV Justice Network. “Far too often, people living with HIV are prosecuted not for causing harm, but simply for living with a health condition – often in ways that are unscientific, discriminatory, and deeply unjust.”

The report highlights the intersection of HIV criminalisation with racism, homophobia, gender-based discrimination, and systemic inequality. In Senegal, for example, prosecutions have disproportionately targeted LGBTQ+ individuals. In the U.S., criminal laws continue to be weaponised against communities of colour, even in cases involving no risk of transmission – such as spitting, or sex with an undetectable viral load.

One of the most alarming cases occurred in South Africa, where a former soldier was sentenced to life plus ten years for rape and attempted murder after failing to disclose his HIV status to a consenting partner – despite no evidence of intent or actual transmission. Advocates warn that such cases equate HIV non-disclosure with sexual violence and undermine decades of public health and human rights gains.

Yet, amidst the setbacks, 2024/2025 also brought some signs of hope. Maryland and North Dakota fully repealed their HIV-specific laws, while Tennessee removed mandatory sex offender registration for HIV-related convictions. Mexico City and Colima repealed vague “danger of contagion” laws, and Ukraine’s parliament voted to remove HIV from its criminal code.

In Zimbabwe, community activism helped block a proposal to re-criminalise HIV transmission. However, a new law was introduced criminalising the deliberate transmission of STIs to children, including HIV – raising fears it could be used against mothers living with HIV, particularly in breastfeeding cases.

Despite these advances, HIV criminalisation remains widespread. A total of 83 countries still have HIV-specific laws, and 23 countries reported prosecutions in this period using either HIV-specific or general laws. The HIV Justice Network warns that without urgent action, the world is unlikely to meet UNAIDS’ target of reducing punitive laws to below 10% of countries by 2030.

“The path forward must be rooted in science, rights, and community leadership,” Bernard said. “We must end laws that punish people for their status, and instead build legal systems that support health, dignity, and justice.”

EPO622 Recent progress and setbacks in HIV criminalisation around the world by Edwin J Bernard, Sylvie Beaumont, and Elliot Hatt was presented at IAS 2025 by Paul Kidd at 13th IAS Conference on HIV Science in Kigali, Rwanda.